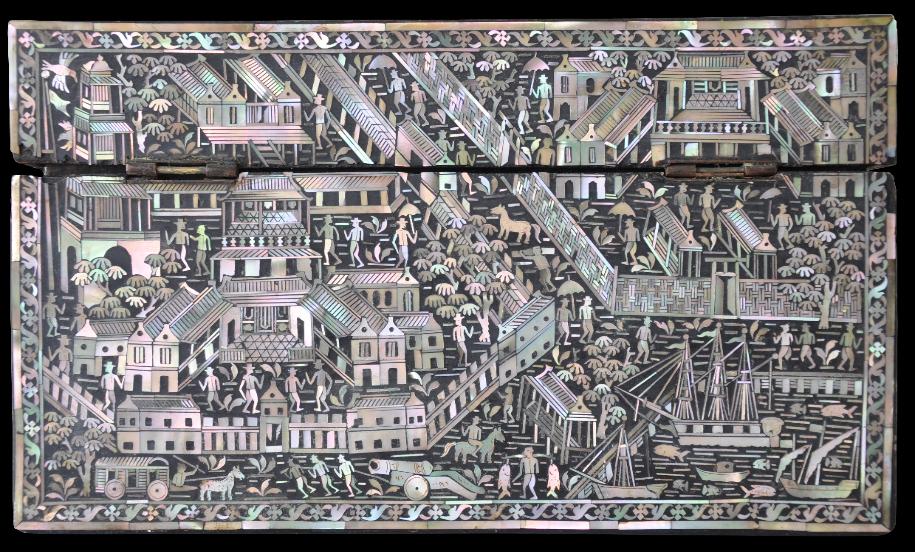

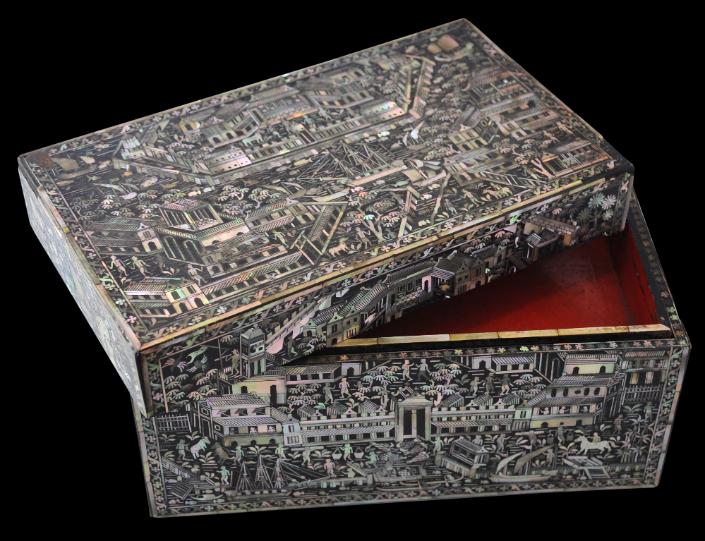

Thai Mother-of-Pearl Betel Box

Exceptional Rare & Important Mother-of-Pearl Inlaid Lacquered Betel Box Showing Foreign Traders

Bangkok, Thailand

circa 1820

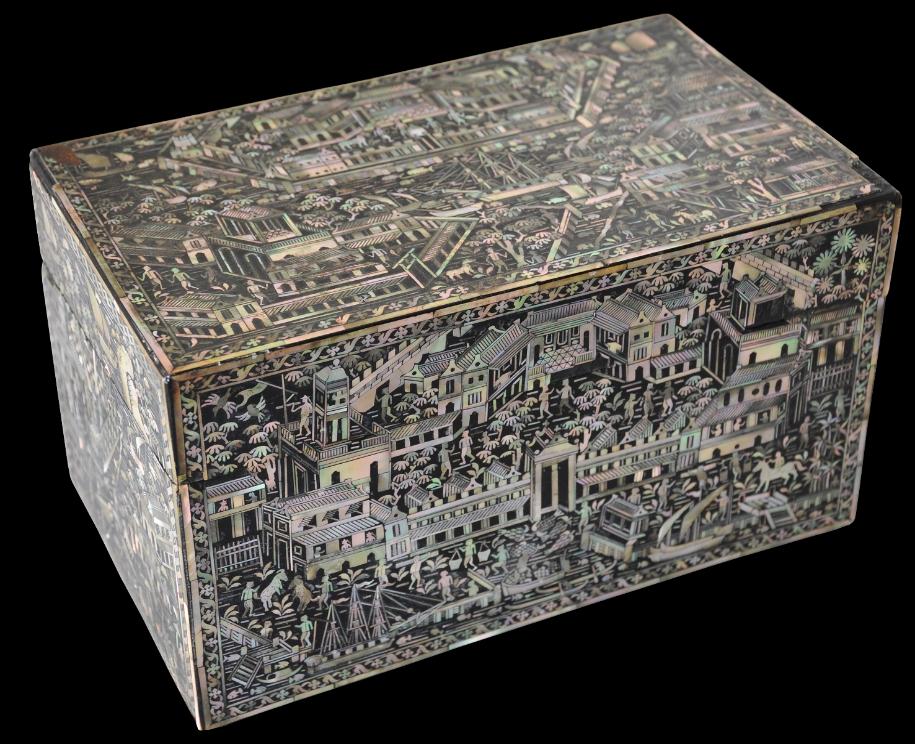

length: 24cm, width: 14cm, height: 13.7cm

Artworks that depict foreigners (farang) and international trade are known in Thai art and are much celebrated but they are relatively rare. Thailand or Siam was never colonised by European powers but there is a long history of interaction between Thailand and Europe through trade and diplomacy. The Portuguese arrived in the then Siamese capital of Ayutthaya in 1511 when Portugal’s Afonso de Albuquerque, the First Duke of Goa, sent Duarte Fernandes as ambassador to meet King Rama Thibodi in 1511. The emissary arrived with gifts and a letter proposing commercial agreements. The Siamese King was interested in trade and political cooperation with the Portuguese. He believed it would help strengthen Siam’s position against the Burmese. From then on, the Portuguese were viewed benevolently and were depicted in temple murals, lacquer decorations and other art objects. A much published gold and black lacquered cabinet, for example, in Bangkok’s National Museum which is thought to date to between 1650 and 1750 shows two large figures, one of whom is clearly European and probably Portuguese, and appears to be attired in a Thai interpretation of seventeenth century dress and armour (see McGill, 2005, p. 156, and Garnier, 2004, p. 188 for illustrations).

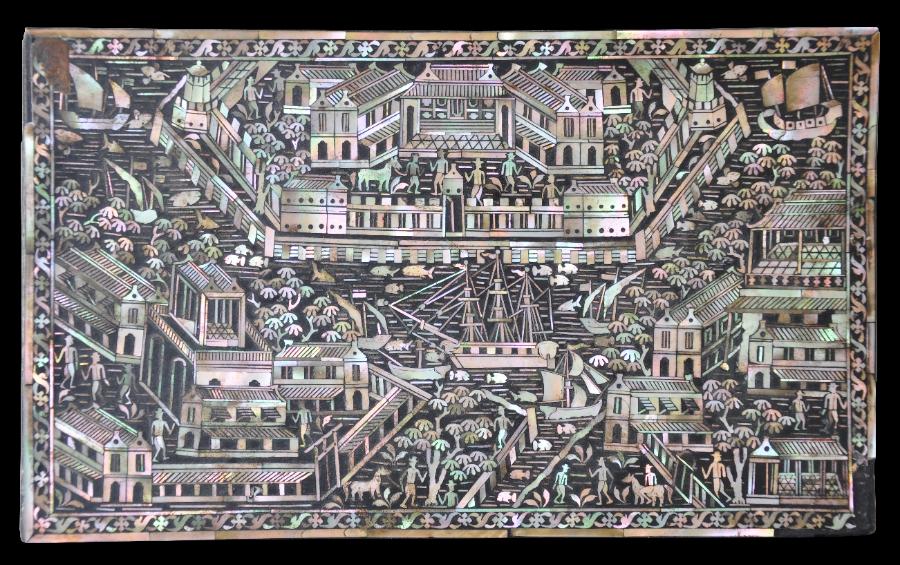

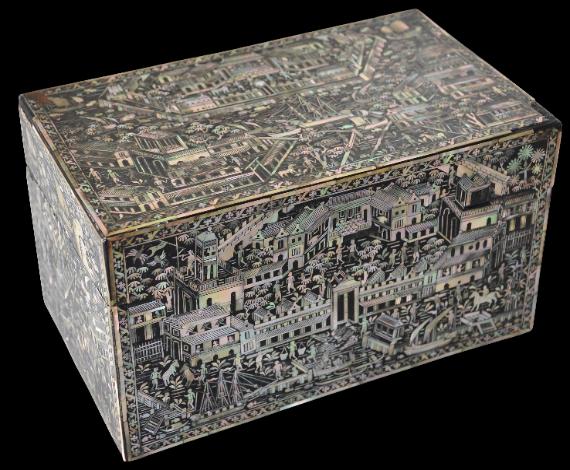

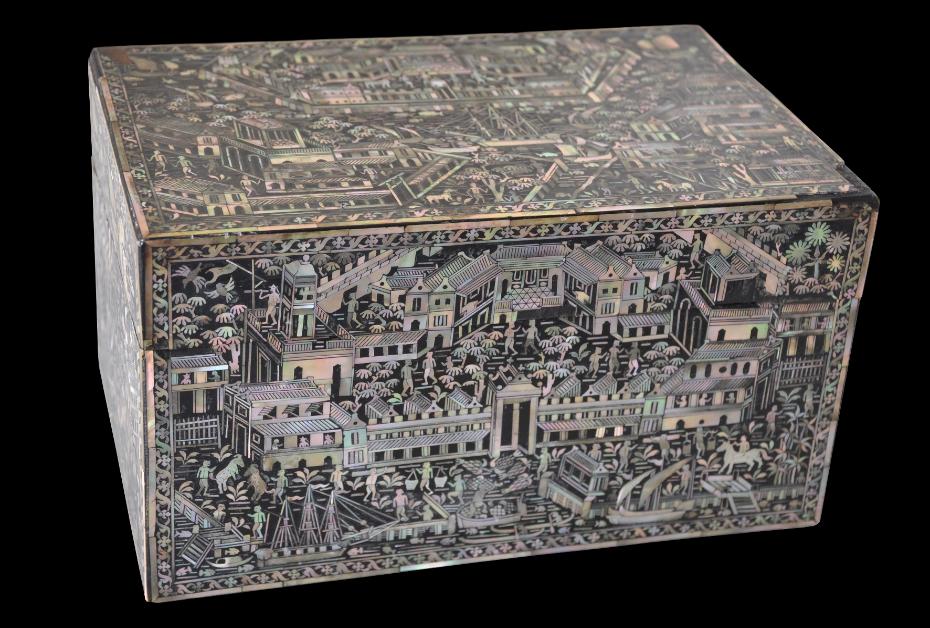

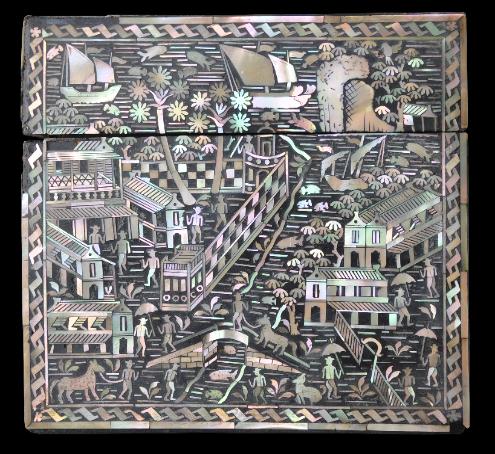

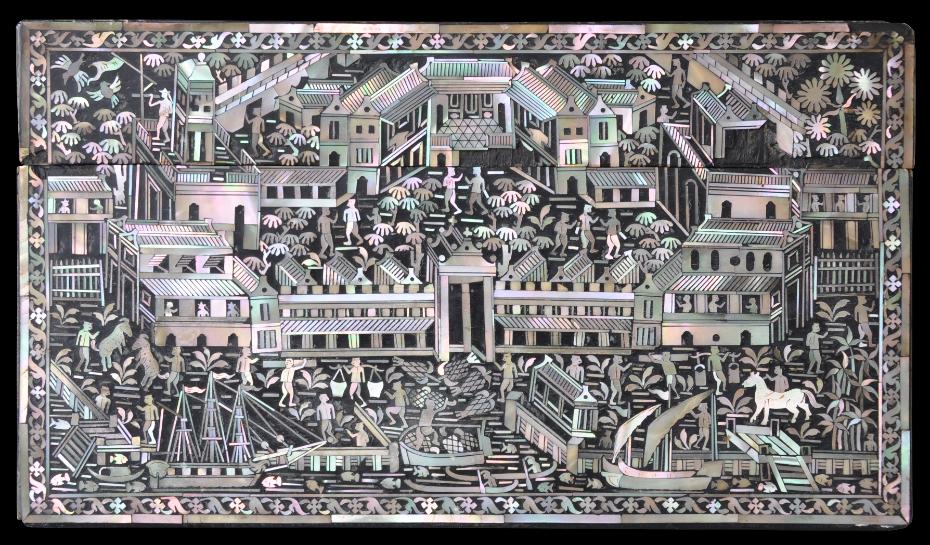

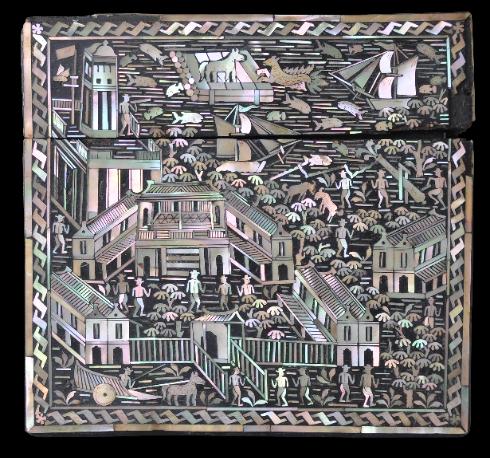

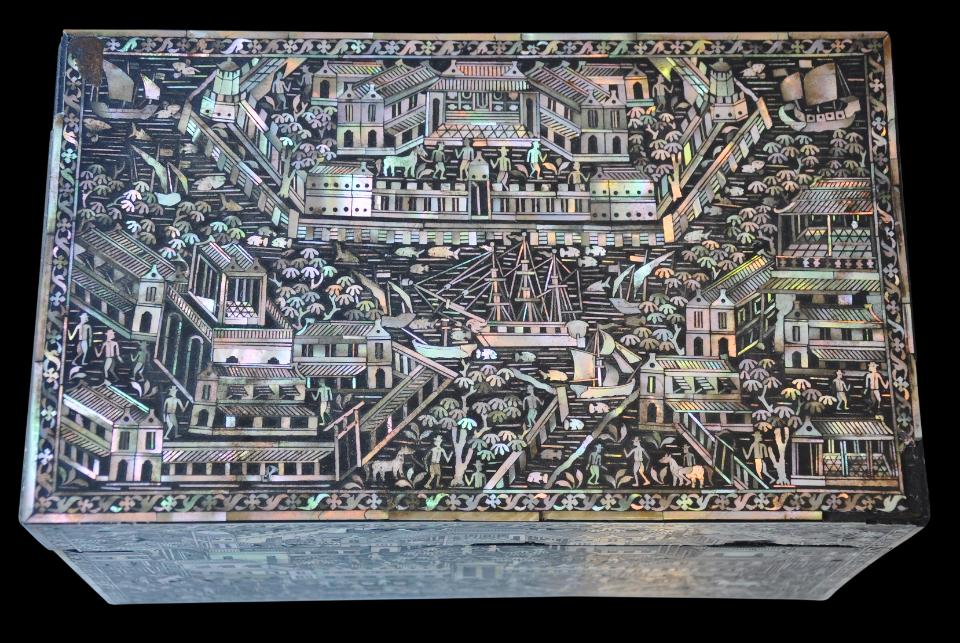

The exceptional and almost certainly unique box here combines the theme of Europeans and international trade with traditional Thai art. European masted ships, Chinese junks and Thai sampans, and European figures with broad-brimmed hats and other figures with flattened heads that most probably represent the cropped hair of local Siamese coolies are all depicted. The scenes show trade and concessions along Bangkok’s Chao Phraya River. The Chinese-style buildings, godowns and enclosures are not unlike the architecture still in evidence on the river today, particularly the area not far from the Oriental Hotel. Fort watchtowers depicted on the top cover are in the same architectural style as the eight fort watchtowers that protected Rattanokasin Island, the two surviving examples today of which are Fort Mahakarn and Fort Phra Sumen, and most probably are meant to represent those towers.

The box is rectangular and of wood. It is profusely decorated on the cover and on all sides with mother-of-pearl inlay embedded in black lacquer, and was intended for use as a betel box. The dimensions of the box are those of betel boxes used in Bangkok during the first half of the nineteenth century. It has a shallow internal tray in orange-red lacquer that can be lifted out and on which the receptacles used to hold the elements of the betel quid would have been stored. (The edges of this tray are inlaid with mother-of-pearl as are the internal edges of the box.) Typically the receptacles would have been of silver, gold or perhaps porcelain. The leaves for the betel quid would have been stored in the box beneath the tray. The cover is hinged and the interior of the box is painted in the same orange-red hue as the tray.

Each side and the cover is finely inlaid with mother-of-pearl, each with a different topographical scene relating to commerce. There are many types of ships and boats. Fish are depicted. Canons are shown here and there including one that is being fired. Bunches of fruits are being loaded onto boats to be traded and sold. Horses are being lead, ridden and in one scene, one horse appears to have fallen into the river. Horse-drawn traditional wooden carts are arriving presumably laden with goods for trade. Everywhere typical secular Thai architecture is shown – some buildings have wooden window shutters that are propped open with sticks to allow the interiors to cool whilst not allowing in monsoonal rain. The attention to detail is extraordinary. All the clutter and frenetic activity expected with a busy port is captured on every part of the box.

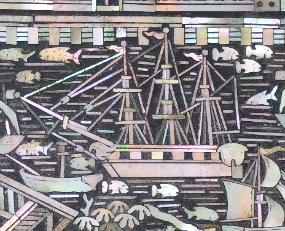

Clues as to the date of the box can be garnered from some of the detail. The European ships portrayed are of the form of the earlier British East Indiaman used in international trade from the 1750s rather than the later clipper type. Clippers had longer, narrower hulls, and rounded rather than blunt sterns. Clippers were introduced to international trade from the around the 1850s. The sailing ships shown on this box however have shorter, higher hulls with square sterns. If the ships have been rendered in the manner of their age then the box pre-dates the mid-nineteenth century.

As mentioned, the architectural style of the forts that were constructed after King Rama I established Bangkok as the new capital in 1782 in the aftermath of the destruction of Ayutthaya by the Burmese in 1767 is mirrored in the forts depicted on the top cover. Today, two of the eight forts that were built remain – Fort Mahakarn and Fort Phra Sumen.

Much of the trade conducted by Europeans with Thailand was not direct with Europe but comprised intra-Asia trade with key ports in the region that in turn were connected with Europe. And the Siamese themselves tended not to be directly involved in long-distance trade which instead was carried out by Chinese, Indian, Persian, and Malay traders as well as the Europeans. The rivers of the Chao Phraya basin were busy with the ships of traders who traded first with Ayutthaya and then with Bangkok. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to trade significantly with Siam, but the British, French and Dutch soon followed. By the mid-seventeenth century, the governor-general of the Dutch East India Company in Batavia was a regular correspondent with the Siamese King on trade and diplomatic matters.

Mother-of-pearl lacquer work has a long history in Thailand. During the early Bangkok period (1782-1824), mother-of-pearl inlay work was so popular that high-ranking members of the royal family were appointed to oversee its production in a bureau known as ‘the Department of Mother-of-Pearl Inlay’ (McGill, 2009, p. 200). The fineness and sweeping, grand nature of the scenes depicted on this box suggest it might well have been a product of the bureau. But by the end of the nineteenth century, the art form started to lose its popularity. The bureau was closed down in 1926.

Typically, the shells from which the shell inlay used was sourced came from the coral reefs along the coast of Phuket and Surat Thani Provinces in Thailand’s south and Chanthaburi and Trat Provinces of the east. Thrones for kings and palace and temple doors were among the larger items lacquered and inlaid with pearl shell. Monks strictly enforced a 19th century rule against the use of precious metals which encourage the use of embellished lacquer. Religious artifacts with mother-of-pearl inlay are also documented as having been presented as gifts to senior monks in Sri Lanka as early as 1814 (Byachrananda, 2001).

The box is a remarkably fine object and undoubtedly would have been costly when it was made. It has documentary historical value, and emphasises the importance of trade to Southeast Asia and particularly the Siamese kingdom. It is a reminder of just how extensive international trade was in the past both within Asia and between Asia and the West – a reminder that such trade is hardly a new phenomenon.

The box is in fine condition given its age and the materials from which it is made. There are some losses to the mother-of-pearl inlay to some of the corners and to the gap where the cover meets the rest of the box. These could be restored but are relatively minor and can be left untouched in our view. The hinges for the cover also have worn through, but for display purposes, this is not apparent when the lid is closed. Indeed, although the hinges have much age, betel boxes of this type need not have had covers that were hinged. Importantly, the internal tray is still present. Overall, the box is in a stable, robust condition. There are no cracks, no flaking, little warping and no repairs. The mother-of-pearl shell that has been used is particularly lustrous and fluoresces with green and pink tones in the light.

References:

Byachrananda, J., Thai Mother-of-Pearl Inlay, River Books, 2001.

Garnier, D., Ayutthaya: Venice of the East, River Books, 2004.

McGill, F. (ed.), The Kingdom of Siam: The Art of Central Thailand, 1350-1800, Snoeck Publishers, 2005.

McGill, F. (ed.), Emerald Cities: Arts of Siam and Burma, 1775-1950, Asian Art Museum, 2009.

Provenance

UK art market

Inventory no.: 1831

SOLD

Fort Phra Sumen in Bangkok (left) and a similar representation on the box.

A canon being fired.

One of several European sailing ships depicted on the box.