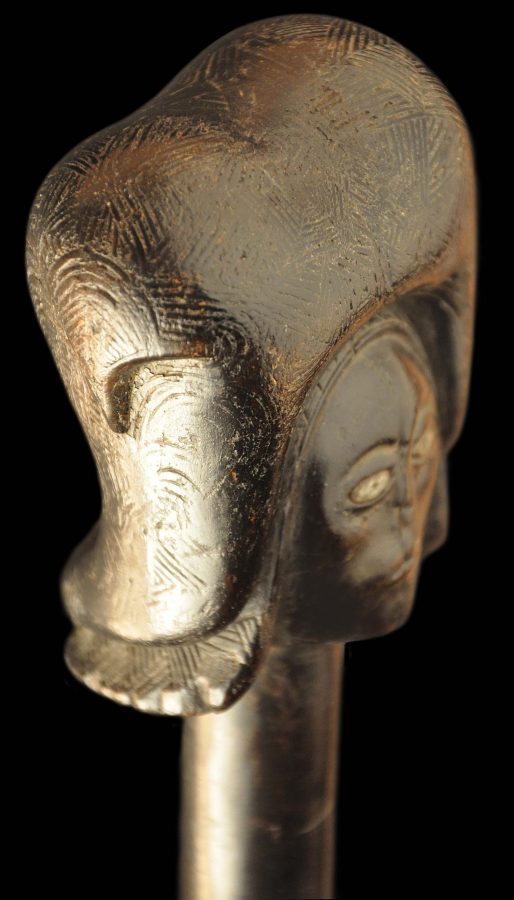

This fine and rare privilege sceptre has a deep, glossy patina. Its age could not be more pronounced. It is carved from a single dark wood and has, as its finial, a particularly finely carved female head. The head demonstrates all the traits of the idealised Ovimbundu woman’s face: prominent eyes, a fine nose and a slightly gaping mouth. Her facial expression is compelling, yet elegant.

Her elliptical eyes, inlaid with lead, are set between very delicately carved eyelids. Her pupils are revealed through the pierced lead inlay. Two fine brows are incised above her eyes. Her prominent forehead is characteristically Ovimbundu. Such a prominent forehead suggests intelligence, thoughtfulness and sensibility.

Her face is separated from her coiffure by a finely incised fringe. This fringe is incised with triangular motifs. These triangular motifs are common in Ovimbundu coiffure carving.

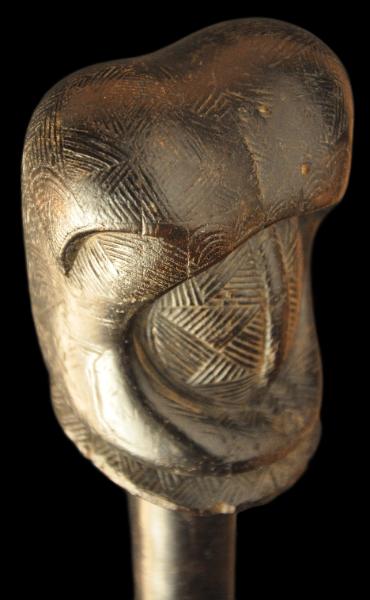

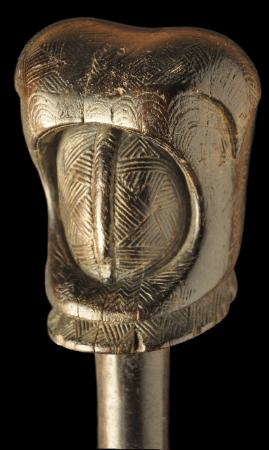

Her coiffure is both high and highly detailed. It is among the very best examples of this type of Ovimbundu carving. It rises from the top of the forehead and sweeps back dramatically. Two humps are visible on top of the coiffure. On the back of the head, the coiffure concaves in to reveal intricate zigzag motifs and a lobe of hair that sweeps backwards – a hint of the woman’s maturity. The entire coiffure is incised with similar repetitive zigzag motifs.

The form of the coiffure may be based in part on that of a colonial Portuguese or European woman (see the last image below). The Ovimbundu were one of the few tribes exposed to the Europeans by the early nineteenth century due to their proximity to trade routes.

Ovimbundu carvers have over the years incorporated European hairstyles into their carving’s aesthetic traits. Some examples of the contemporary European hairstyles are shown below.

The sceptre has an almost ebony-like dark hue – a product of it having been darkened at the time of manufacture. The patina is now deep and glossy. Some pleasing de-colouration to the handle is noticeable – a product of ceremonial and ritual handling.

A similar Ovimbundu female head carving can be seen on a cane handle, in Musée Royal de l’Afrique Central, Tervuren. This was sourced in 1950, although it already had age.

Sceptres such as the example here were prestigious items owned by Ovimbundu chiefs in what is now Angola. Their forms represent the positive qualities the chiefdoms would wish to cultivate within. Typically such sceptres were presented to the sons of chiefs during their transition to adulthood.

Ovimbundu carvings, particularly of the female figures, were aesthetically influenced by Chokwe carvings. (The Chokwe are another of Angola’s important ethnic groups). Ovimbundu carvings were also influenced by the royal art of the neighbouring Luba kingdom in the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo.

All of these influences were cultivated along trade routes that penetrated the region during the 19th century. The Ovimbundu, Chokwe, Luena and related tribal groups in the region all have similar sceptres with the particularly striking characteristic of elaborate hairstyles or headdresses that adorn both male and female finial heads.

The Ovimbundu are a Bantu-speaking ethnic group living in southern Angola, which comprises over 20 indigenous chiefdoms. The Ovimbundu were the main coastal link to the Portuguese-sponsored trade routes with Central Africa. The merchants and chiefs became wealthy through this trade and would often commission objects of art to illustrate their political and financial status. The authority of an Ovimbundu chief was not hereditary – a council elected a sovereign, but he was chosen only from among the members of the royal clan.

References

Bacquart, J. B., The Tribal Arts of Africa, Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Ginzberg, M., African Forms, Skira editore, 2000.

Pethica, T., Klopper, S. & Nettleton, A., The Art of Southern Africa: The Terence Pethica Collection, 5 Continents, 2007.

Robbins, W. M. and Nooter, N. I., African Art in American Collections, Smithsonian Institution, 1989.