This early ivory carving of the agonizing Jesus on the Cross is a good example of early 17th century Christian work done for the Portuguese market in Sri Lanka (Ceylon). Sri Lankan Christian ivories for the Portuguese market are relatively rare and particularly early when it comes to Christian art produced in Asia on behalf of European clients. The example here is similar with its narrow waist and elongated torso to a seventeenth century Ceylonese-Portuguese Christ illustrated in Stratton-Pruitt (2013, p. 110), and to another example illustrated in Bailey et al(2013, p. 105) attributed to late 16th century Sri Lanka.

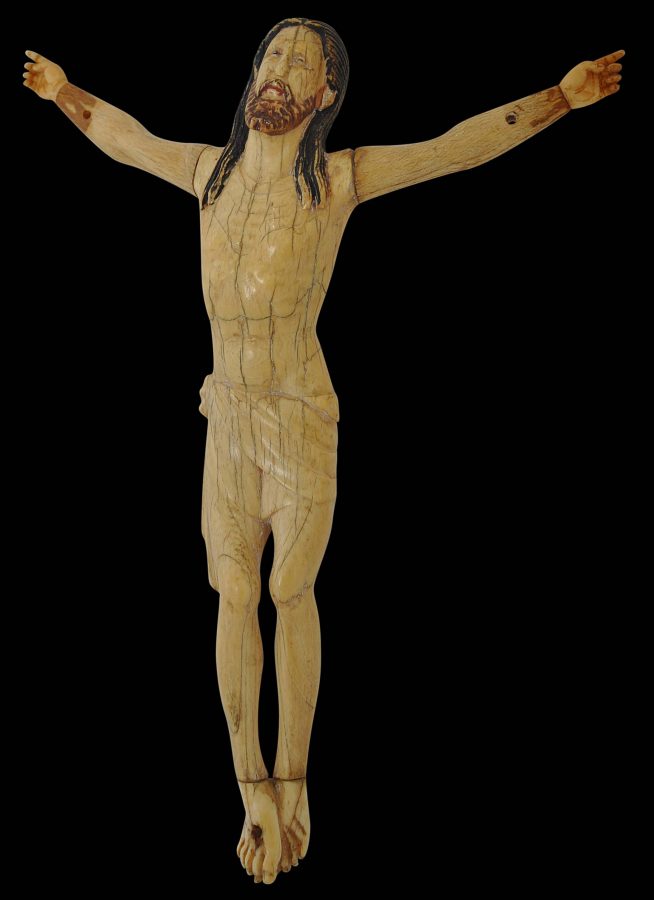

The body of the image is well rendered with ribs, a raised rib cage and the muscles of the abdomen well defined. The arms are long and thin and elevated above the horizontal position.

The hands and feet have been carved separately and joined at the wrist and ankles.

The head leans slightly to the figure’s left and is raise upwards. The eyes are almost closed and the expression is one of exhaustion. It seems to be the moment when Jesus asks in a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?’ – translated as, ‘My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?’ “(Mark 15:34)

The beard is copious and ends in two small points. Christ’s right foot is crucified over the left. The image’s fingers are intact and delicate. A small hole to the top of the head would have allowed a silver halo or crown to be inserted.

The hair is well defined in long strands and falls over the fronts of both shoulders as well as down the back. The loin cloth has multiple folds and has a big bunched knot on the right hip.

Both the beard and hair are coloured with dark brown pigment.

Interestingly, the feet retain the remnants of a single nail but the nail holes for the hands are not in the hands but the forearms. The body is particularly arched and so additional holes are in the back of the figure to allow it to be secured to a cross.

Early on, Sri Lanka was known as a place with numerous elephants and an abundant supply of ivory. The palace workshops of the kingdoms of Kandy and Kotte already were producing fabulous items from carved ivory for the local rulers. This was recognised by the Portuguese soon after their initial contacts with the island, and it was not long before the island’s ivory carvers began to receive commissions from the Portuguese for items in carved ivory that they could sell into their home market back in Portugal.

Click here for an example of an early Sri Lankan Portuguese market ivory Christ in the Victoria & Albert Museum. See Bailey et al (2013, pp. 101, 123, 124) for illustrations of three related Singhalese (Sri Lankan) ivory Crucified Christs in Portuguese collections. Vassallo e Silva writing in Bailey et al(2013, p. 102) says ‘the sculptures of the Crucified Christ must be some of the most remarkable creations in ivory in Ceylon.’

Christian ivories from South Asia such as this example made their way as direct imports to Europe, particularly to Spain and Portugal, where they entered the treasuries of churches and monasteries. Others were sent to Portugal and Spain’s dominions such as Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines from where they might also have been exported to Europe. Others still entered aristocratic collections and European cabinets of curiosities as curios and collector’s pieces. Juana de Cordoba y Aragon, the Duchess of Frias, is known to have owned around fifty such pieces in 1604 (Trusted, 2007).

The condition of the piece here is very good. There are no losses to the extremities. There is a small chip to the back of the right leg where it joins the foot – but this is barely discernible. Overall, it has a fine, yellowed patina consist with its considerable age.

References

Bailey, A., J.M. Massing & N. Vassallo e Silva, Marfins no Imperio Portugues/Ivories in the Portuguese Empire, Scribe, 2013.

Brazilian Baroque: Decorative and Religious Objects of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century, from the Museum of Sacred Art of Sao Paulo, Brazil, Governo do Estado de Sao Paulo, 1972.

Stratton-Pruitt, S.L., Journeys to New Worlds: Spanish and Portuguese Colonial Art in the Roberta and Richard Huber Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art/Yale University Press, 2013.

Trusted, M., The Arts of Spain: Iberia and Latin America 1450-1700, V&A Publications, 2007.