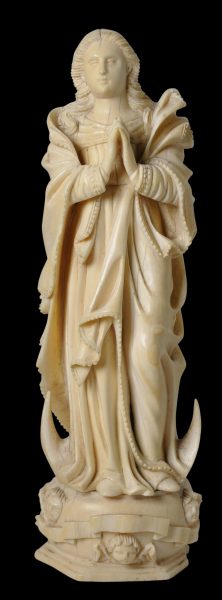

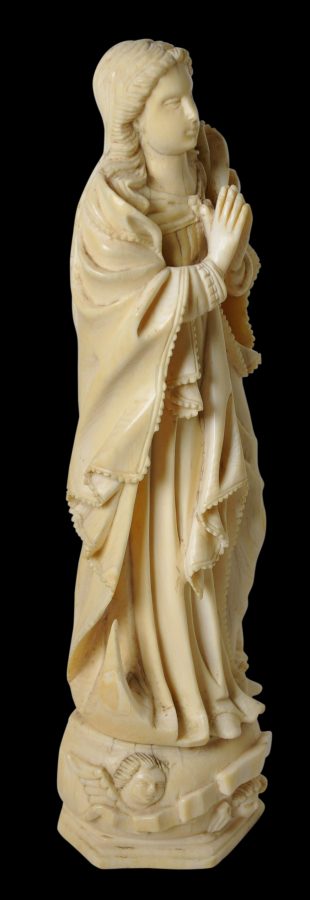

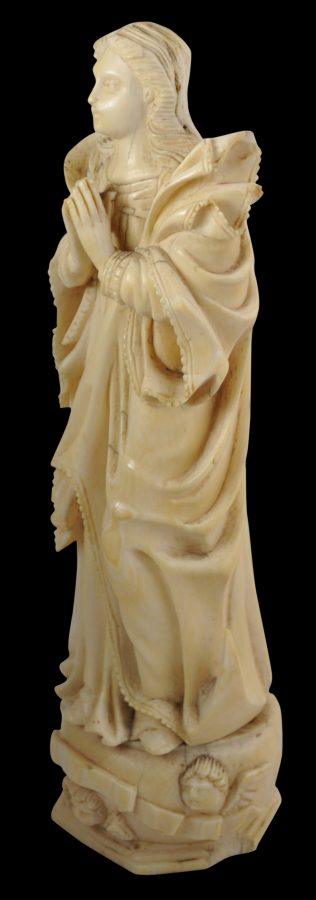

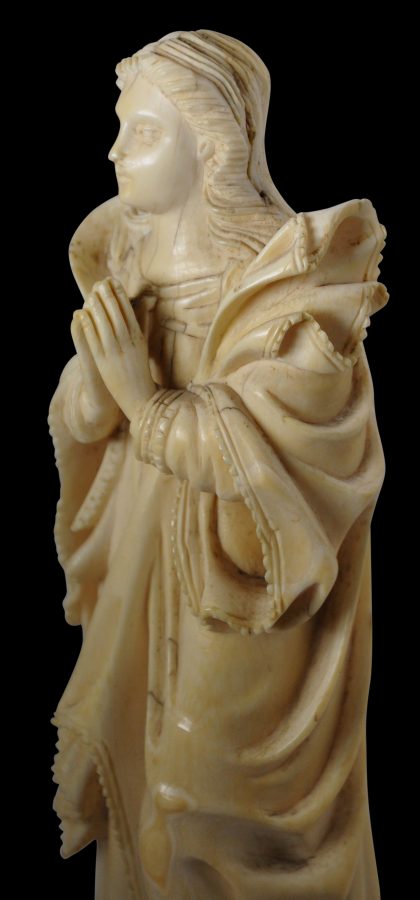

This good-sized image of Mary, the Mother of Jesus, is as the Immaculate Conception of Mary. It shows the Conception (as in being conceived) of Mary as the Virgin and thus she is without stain or blemish. Ivory was an ideal material to show this attribute of Mary, for it is without stain or blemish, or at least can be perceived as such.

There rendering here has all the characteristics of an ivory from the Portuguese colonial enclave of Goa: Mary’s hair is shown as well-defined, flowing locks; the hair is also pulled back over the head in the Indian manner; she is in flowing garb that is almost sari-like, with plenty of pleats to suggest movement; the neckline and cuffs of her dress are pearled or serrated; her left leg is placed slightly forwards so that the outline of her left knee is apparent through her dress; and her feet rest on a crescent moon or medialuna. The crescent moon, in turn, rests on an ivory block carved with seraphim.

Christian ivories from India such as this example made their way as direct imports to Europe, particularly Spain and Portugal, where they entered the treasuries of churches and monasteries. Others were sent to Spain and Portugal’s dominions such as Mexico and the Philippines from where they might also have been exported to Europe. Others still entered aristocratic collections and European cabinets of curiosities as curios and collector’s pieces. Juana de Cordoba y Aragon, the Duchess of Frias, is known to have owned around fifty such pieces in 1604 (Trusted, 2007).

Goa had a fractious history before coming under Portuguese control. It came under the governance of the Delhi Sultanate in 1312. But the Sultanate’s hold over the region was weak. By 1370, the region was surrendered to the Vijayanagara empire. The Vijayanagara monarchs held the territory until 1469, when it fell to the Bahmani sultans of Gulbarga. With the fall of that dynasty, the area fell to the Adil Shahis of Bijapur who established as their auxiliary capital the city known under the Portuguese as Velha Goa. In 1510, the Portuguese defeated the ruling Bijapur kings with the help of a local ally, Timayya. They founded a permanent settlement in Velha Goa (Old Goa). With the Portuguese, came Christianity. From the sixteenth century, Goa which formerly had been a remote province on the periphery of kingdoms, became an eastern trading capital of the Portuguese empire and the seat of Christian imperialism and influence whose influence stretched from the Cape of Good Hope to the Sea of Japan.

The Portuguese expanded their possessions around the region so that by mid-18th century the area under occupation included most of Goa’s present day state limits. In 1843 the capital was moved to Panjim from Velha Goa.

After India gained independence in 1947, Portugal refused to negotiate with India on the transfer of sovereignty of its Indian enclaves. In December 1961, the Indian army annexed Goa and several smaller Portuguese possessions, ending Portugal’s 400 year presence in the Indian sub-continent.

Many Goans converted to Christianity under the Portuguese. Local religious art developed syncreatic elements: it was predominantly Christian but incorporated Hindu Indian influences. The Jesuits played a critical role in Goa: Francis Xavier, the Spanish-born pioneering Roman Catholic and co-founder of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) was ordered by Ignatius Loyola, the principal founder of the Jesuits, on behalf of the Portuguese king to undertake a mission to the Portuguese East Indies. The king had become concerned that Christian values in the possessions had become deteriorated. Xavier left Lisbon in April 1541, and after first visiting Mozambique he reached Goa in May 1542, where he spent the next three years strengthening the position of the Church.

Thereafter, the Jesuits played a key role in developing the Church’s infrastructure in Goa: churches, monasteries and Catholic schools were built.

This carved ivory image is an excellent and increasingly scarce reminder of India’s complex, mixed heritage but also of a time when Portugal was a great seafaring and trading nation – a reminder that globalisation is hardly a new concept.

There are no repairs or noteworthy cracks. There is some minor loss to the serrated edge of Mary’s dress in just one small area. The hollow of the tusk has been filled-in with a wooden block.

References

BBL, De Goa a Lisboa, Europalia 91, 1991.

Carreau, R., Devotion Baroque: Tresors du Musee de Chaumont, Somogy Editions D’Art, 2009.

Levenson, J.A, et al, Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th & 17th Centuries, Arthur M Sackler Gallery, 2007.

Manuel Fores, J., et al, Os Construtores do Oriente Portugues, Comissao Nacional Para as Comemoracoes dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, Porto,1998.

Museum of Christian Art, Museum of Christian Art, Rachol, Goa, 1993.

Pal, P., A Collecting Odyssey: Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art from the James and Marilynn Alsdorf Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1997.

Pereira, J., Churches of Goa: Monumental Legacy, Oxford University Press, 2002.

Trusted, M., The Arts of Spain: Iberia and Latin America 1450-1700, V&A Publications, 2007.

Vickers, M. et al, Ivory: A History and Collector’s Guide, Thames & Hudson, 1987.