Personal Adornment & the Subjugation of Women

Jewellery and other items of personal adornment often have been used to demonstrate the social status of women and the wealth of her family, across time and across cultures. Some items of adornment though cross the line from being merely decorative to actually demonstrating that a women does not need to work or at least does not need to engage in physical labour because she or more usually her family or her husband were wealthy enough to afford servants. Sometimes these adornments go so far as to render the wearer immobile or to severely restrict her movement or even to maim her. The notion that her circumstances (or at least those of her family or husband) meant that she had a life of leisure often could not merely be hinted at – they had to be clearly demonstrated, often with disturbing effect.

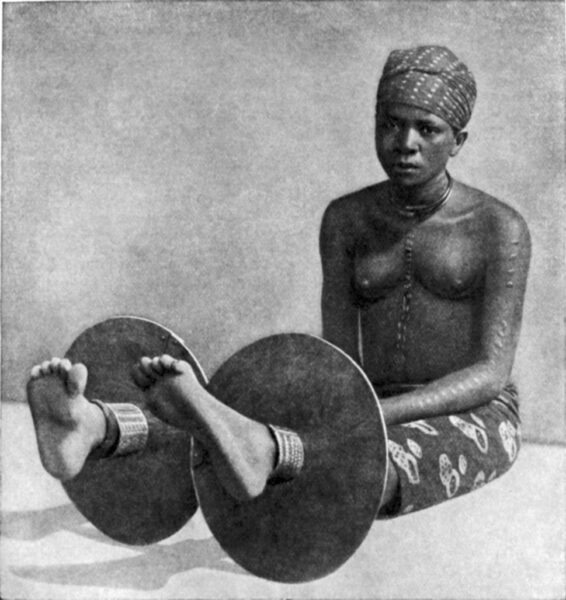

This pair of ogba anklets from the Igbo people of Nigeria is a case in point. Very much status symbols, they were made of brass with a large diameter with a metal leg tube in the middle for the ankle. Once on, the anklets were worn at all times and could not be removed by the wearer. A brass smith was needed to hammer the anklet on, but also to remove it. Pieces of fabric were worn between the anklet and the skin, to reduce chafing.

Smiths would hammer these dinnerplate-sized anklets into shape and construct them around the ankles of women from high-ranking Igbo families. Usually, they were only removed to replace them with even larger anklets. Such anklets restrained the mobility of the women who wore them and as such are very much in the tradition of showing that the woman’s husband was successful and wealthy to the point that his wife had no need to engage in physical labour. Walking in them was difficult and the women who did wear them developed a characteristic gait, which was regarded as a sign of feminine beauty and wealth.

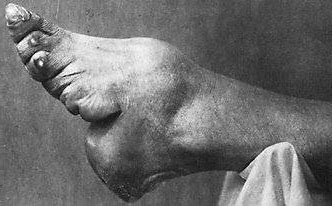

But the most overt case of rendering women unable to walk, at least not without great difficultly, was the practice of foot binding in China. Foot binding is believed to have started during the late Tang dynasty, around AD 950. The practice spread from the court to the nobility and then throughout the rest of (Han Chinese) society over subsequent centuries. The practice was banned in 1911 by the Republican government, although it persisted in some of China’s more remote areas until about 1940. Young girls would have their feet bound tightly with strips of cloth to compress the bone structure so that the toes and upper section would be forced under the foot to essentially force the entirety to become a club foot. The ideal length of a woman’s bound foot was said to be three inches (about 7.5 centimetres) but in reality few bound foot shoes are this short. Most extant examples are four to five inches (10-12.5 centimetres) which makes the shoes/boots here at the smaller end of the scale.

The shoes below (formerly in our gallery and now in a private collection) are unusual in that they also included ankle cuffs, but the idea was the same: the feet were compressed to fit into the tiny ‘shoe’ or foot covering at the end.

The truth hidden behind the elegant though incongruous shoes is below:

Long fingernails and fingernail guards were another way for Chinese to demonstrate that their womenfolk did not engage in manual labour. The fact that a woman had at least one long fingernail was emphasised by wearing a guard over the nail. The example below, formerly in our gallery and now in a private collection, is one such example. It is made of tortoiseshell with gilded silver mounts.

Hammam clogs, such as the examples below, worn in the Ottoman empire were another way of rendering women immobile to demonstrate their wealth, even if only temporarily. Such clogs were designed for a wealthy Turkish or other Ottoman woman so that when worn she would be elevated above a wet and dirty floor, often in the public bathhouse or hammam. Walking, however, required the assistance of an attendant, and the higher the clog, then the more attendants who would be needed, so particularly high clogs became status symbols. They implied that you could afford many attendants to help you walk. Their Arabic name – qabqab – derives from the sound they made when they were being used on a hard surface.

Qabqab clogs being worn below in Ottoman Hungary.

Other examples of adornment meant to incapacitate women as a show of wealth abound. The brass coils worn by the ‘long-necked’ women of Burma, also known as the Padaung, or the Yan Pa Doung or the Kayan Lahwi, are one. The practice of adding coils around the neck had the appearance of lengthening the neck, but in reality, it pushed down the collar bone, and compressed the rib cage. An example of these coils currently in our gallery appear below.

A group of Paduang women caused a sensation in London when they visited in 1935.

Finally, of course in our modern, more enlightened times, women are not immobilised by items of personal adornment. We can look back at other cultures with a degree of self righteousness at what was done in the name of fashion and demonstrating wealth. Or maybe not.

Receive our monthly catalogues of new stock, provenanced from old UK collections & related sources.

See our entire catalogue of available items with full search function.

______________