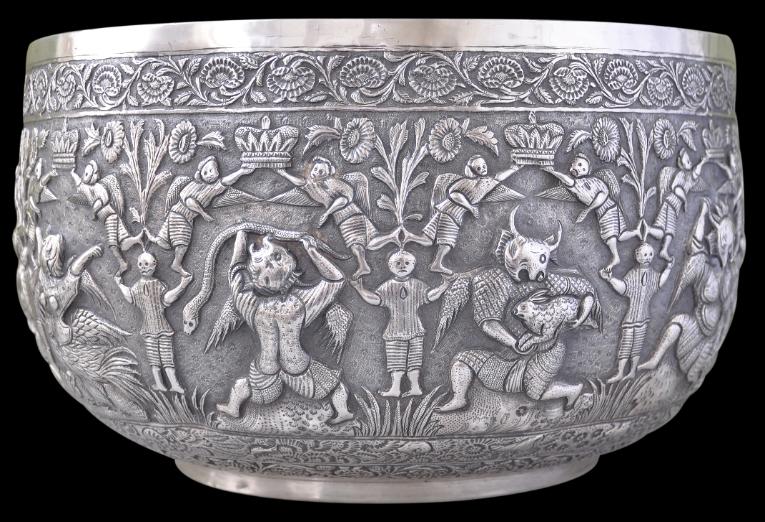

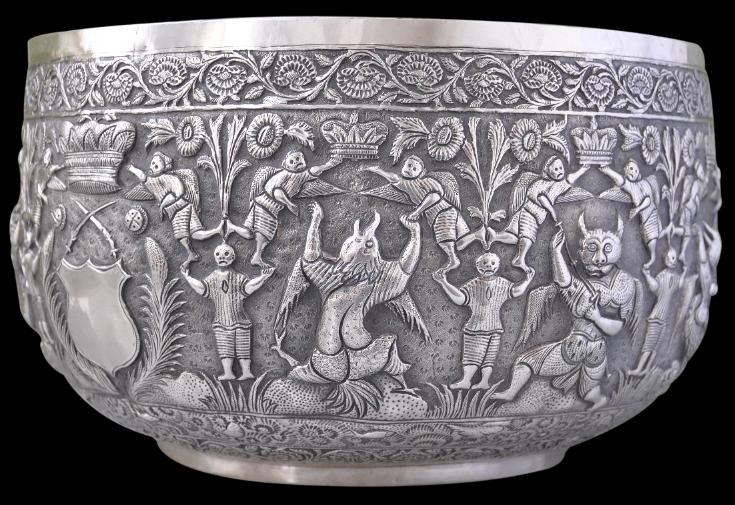

Lucknow Colonial Indian Silver Bowl

Large Silver Bowl Chased with the Nawab of Oudh’s Crest Motif

Lucknow, India

circa 1860

diameter: 29cm, height: 16.2cm, weight: 1,512g

The form and themes on this relatively large solid-silver bowl are typically Lucknow, but the schematic layout of the motifs is unusual. The figures and other elements are more densely arrayed than is usual and include nine winged demon-headed creatures, all between fine floral borders.

Also, the chased decoration incorporates elements from the royal emblem of the Nawabs of Oudh (Awadh), the hereditary rulers of the state of Oudh of which Lucknow was their capital. These form the arches over the mythical creatures with a figure dressed in striped Lucknow

paijamas (the English word ‘pyjama’ is a corruption of this word) between each one and hold up two others which in turn hold the crown of Oudh to complete the arch. (Sometimes these figures are represented as winged mermaids, but not always – the form of the emblem of the Nawabs appears to have been modified with each Nawab.) Bizarrely, the silversmith appears to have given the paijama-clad figures skulls in place of their heads.

There is a prominent, blank armorial cartouche to one section of the bowl, which has fine leafy flourishes to either side and above it, a pair of crossed swords and a large Oudh crown. The base is engraved with an elephant surrounded by a floral border.

Was the silversmith making a comment on the state of Oudh with this odd rendering? Could the substitution of heads with skulls in the Nawab’s emblem be a statement on the demise of the political power of the Nawabs at the hands of the British?

The ruling family of Oudh established themselves as independent hereditary rulers during the collapse of Mughal power during the early eighteenth century.

The strategic position of their capital and the Oudh province, prompted the British to use them as a buffer state between their own territories in the east, and the west. However the British used the inevitable intrigue and jockeying in the Oudh court to exert greater and greater influence. By the turn of the nineteenth century they managed to virtually exercise a veto right on the succession. The Nawabs devoted much of their time trying to project the outward signs of their sovereignty and regality, rather than exerting their power. Accordingly, Lucknow became an important centre for court arts.

Wajid ‘Ali Shah was the last Nawab of Oudh. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Nawabs had lost their political and military usefulness to the British, and so the British under Dalhousie, Governor General of the East India Company, annexed the Kingdom outright in 1856 on the grounds of internal misrule. It was in Oudh where the first great revolt of Indian Independence started in 1857. The uprising saw the British shell Oudh government buildings in Lucknow and the deaths of thousands. There is a famous photograph by the photographer Felice Beato which shows the interior of the Sikander Bagh after the slaughter of 2,000 rebels by the 93rd Highlanders and the 4th Punjab Regiment in 1858. Skulls and exposed rib cages are strewn everywhere against the ruined, shelled portico of a once-grand building, although it is believed that the bones were arranged for dramatic effect for the sake of the photograph.

Meanwhile Wajid ‘Ali Shah was exiled to Calcutta with most of his family.

Interest in the arts of Lucknow has been heightened with an exhibition ‘India’s Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow’ staged at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art December 12, 2010 to February 27, 2011, and at the Guimet Museum in Paris April 6 to July 11, 2011.

The bowl is accompanied by an old black and white photograph which shows it and a (non-matching) Indian silver plate. On the reverse of the photograph is the handwritten message ‘Purchased from the Jordan March Estate in the 1940s in Boston, Mass.’

The bowl is in excellent condition.

References

Llewellyn-Jones, R. (ed.), Lucknow: City of Illusion (The Alkazi Collection of Photography), Prestel, 2006.

Trivedi, S.D., Masterpieces in the State Museum, Lucknow, 1989.

Markel, S. et al, India’s Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow, LACMA/DelMonico Books, 2010.

Provenance

UK art market; and apparently acquired in Boston, US, in the 1940s from the Jordan March Department Store.

Inventory no.: 1783

SOLD

Muhammad ali Shah (ruled 1837-42) wearing the crown of the Nawabs of Awadh as depicted on the bowl.

The Jal Pari (the Mermaid Gateway), circa 1865. The gates were demolished around 1870. The gateway is emblazoned with an example of the emblem of the Nawabs.