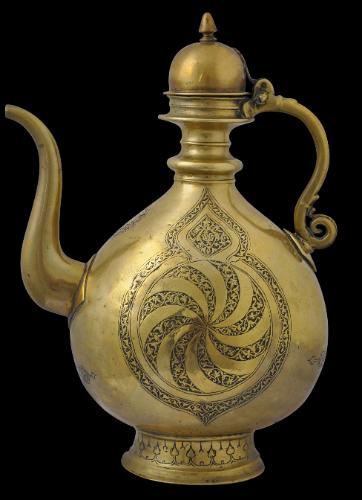

Mughal-Safavid Brass Ewer

Engraved Brass Ewer

Northern India

circa 1700

height: 36cm, width: 26.5cm, weight: 2,315g

This unusual and particularly refined ewer is North Indian but in the manner of Safavid brassware.

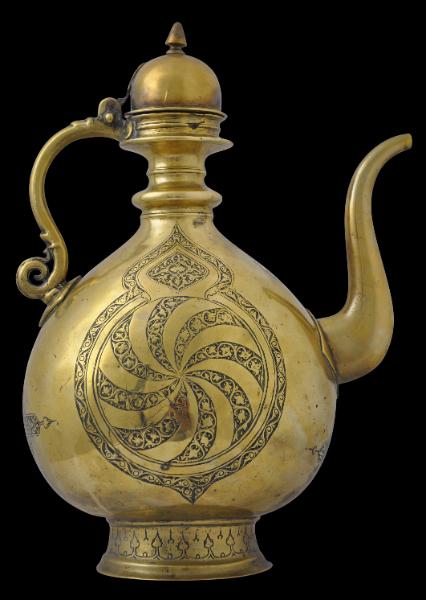

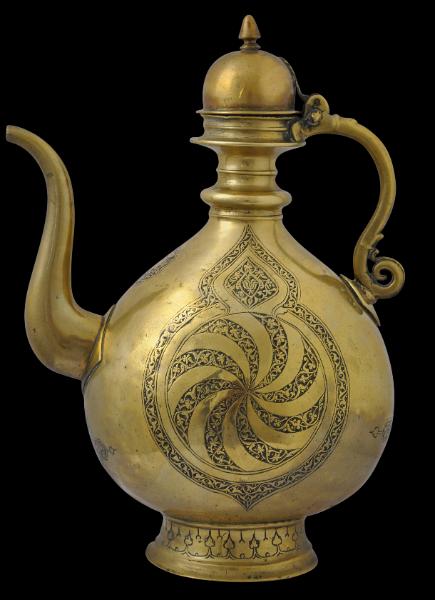

It is large, heavy to hold, and of elongated, flattened, spherical form. It sits on a slightly flared foot; has a plain, domed, hinged lid (which is original); a plain, ‘S’-shaped spout; and a small handle with a tightly-curled ending applied to the body of the ewer by means of a diamond-shaped lozenge. The shape is similar to porcelain ewers imported to Persia from China, but also to locally made porcelain copies of Chinese ewers (see Melikian-Chirvani, 2007, p. 256, for an example of the latter.) Indeed, the influence of Chinese porcelain on Safavid metalware is characteristic.

The ewer is all the more striking by being engraved on both sides with a prominent radiating swirl comprising bands of split-palmette leaf arabesques against a hatched background. The bands widen as they radiate from their point of origin.

These swirls mirror the decoration on a well known and magnificent watered steel shield where similar swirling bands are achieved by chasing that has been enhanced with gold highlights. The shield is attributed to sixteenth century Iran and is now in the Kremlin in Moscow (for illustrations, see

The Tsars and the East, 2009, p. 32 & the cover).

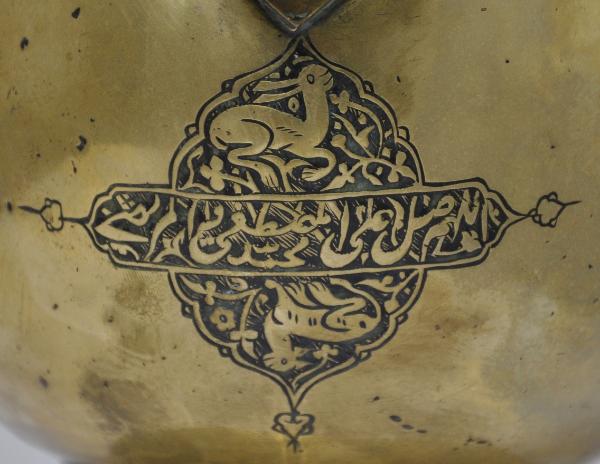

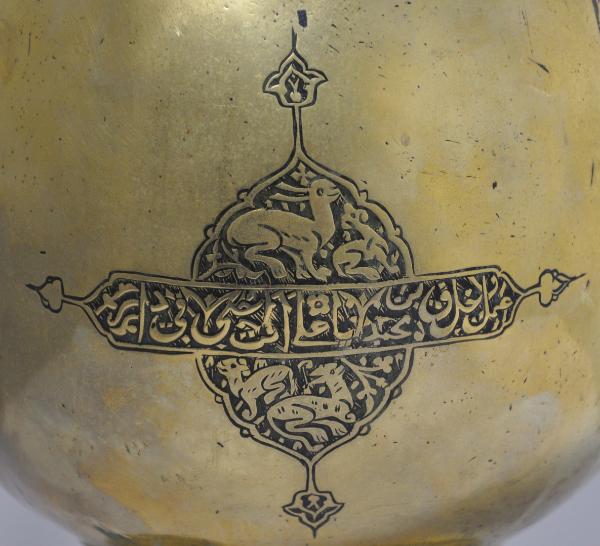

The ewer has two bands of

nasta’liq inscriptions, one beneath the spout and the other beneath the handle, laid out across two cartouches engraved with hares. Elsewhere, decoration includes ample use of the split-palmette leaf arabesque. A cartouche above the spout is engraved with a fine antlered deer, foliage, flowers and hatching.

The bold decoration to both sides of the ewer incorporating the central radiating swirl is almost identical. However, the rounded lozenge-shaped medallion above the swirl differs on each side. On one, it incorporates a stylised lotus motif, which is not present on the other. The lotus motif at once demonstrates the influence of the east – China, India and so on – but also relates to the lively Safavid aesthetic, emulated in Mughal India.

Examples of published Safavid brasswork from which this ewer draws inspiration include a hamam pail dated 1590-93 (see Melikian-Chirvani, 2007, p. 312); a lamp stand dated 1580-90 (see Melikian-Chirvani, 2007, p. 344); a hamam ladle dated to the 16th-17th century (Folsach, 2001, p. 329); a kashkul dated to the second half of the 16th century (Canby, 2007, p. 60); two lamp stands attributed to around 1600 (Canby, 2009, pp. 86-7); and a spherical ewer dated 1603 and in the Victoria & Albert Museum (see

here

).

The ewer, with its low relief engraving that includes medallion and other cartouches decorated with a hatched background that has been darkened, fits squarely in the Iranian sixteenth-seventeenth century canon. Canby (2009, p. 87) observes in relation to a columnar brass Safavid torch stand, that ‘almost all of the examples that are assigned to the last quarter of the sixteenth century or early seventeenth century are made of cast brass with low relief decoration in the background. A black substance was added to the hatched background to provide contrast with the brassy colour of the decoration.’

The ewer can be seen to be in keeping with the new aesthetic that emerged in brassware in Iran around 1550 with the Safavids. The Safavids were descended from a family of Turkmen Sufi sheikhs from Ardabil, in what is today Azerbaijan. The Safavid Empire reached its political and cultural zenith under Shah Abbas I (1587-1629). The arts flourished, miniature painting and ceramics among them, the latter was particularly influenced by Chinese porcelain.

When it came to brassware, the aesthetic featured fine engraving work that incorporated stylised plants and other motifs in low-relief against a hatched ground, that, as mentioned, usually was filled with a black compound. The decoration tended to be arranged in bands or cartouches that matched the shape of the object, and poetic inscriptions in

nasta’liq script also was often incorporated. Figurative and animal motifs that had been absent for more than 150 years also reappeared.

Stylistically, the ewer fits well in this aesthetic. Correspondingly, it has a superb patina. Its contours have been softened by age and handling. In terms of condition, it is free of any splits, losses, dents or repairs. It is a magnificent item overall.

References

Canby S., et al, Spirit & Life: Masterpieces of Islamic Art from the Aga Khan Museum Collection, The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2007.

Canby, S.,

Shah ‘Abas: The Remaking of Iran, The British Museum, Press, 2009.

Folsach, K., von,

Art from the World of Islam: in the David Collection, 2001.

al Khemir, S.,

From Cordoba to Samarqand: Masterpieces from the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Musee du Louvre Editons/5 Continents, 2006.

Loukonine, V., & A. Ivanov,

Persian Lost Treasures, Mage Publishers, 2003.

Melikian-Chirvani, A.S.,

Le Chant du Monde: L’Art de l’Iran Safavide 1501-1736, Somogy Editions D’Art, 2007.

The Tsars and the East: Gifts from Turkey and Iran in the Moscow Kremlin, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2009.Zebrowski, M.,

Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India, Alexandria Press, 1997.

Provenance

UK art market; private collection, Scotland

Inventory no.: 2230

SOLD