The British Museum’s ‘Silk Roads’ Exhibition

Does the world need another exhibition and another book (this time, in the form of the exhibition catalogue) on the Silk Road? The answer is yes, because this time the curators responsible for the new ‘Silk Roads’ exhibition at the British Museum (26 September 2024 – 23 February 2025) have actually got it right. Art historians for the most part do not study any economics as part of their formal training and so generally have a hard time explaining practical aspects of world history such as how cultural and related objects moved around and were traded. They discover that a thousand years ago an item produced somewhere in Asia turns up in Europe and vice versa and they are genuinely surprised and even mystified. That an object could have travelled so far at that time seems like a real ‘discovery’.

For any economist however, it’s a something of a yawn. There is nothing magical or new about world trade. It has been going on for millennia. But for many art historians, it is a revelation. And so this has given rise to the concept of the ‘silk road’ – the oh-so-surprising concept that silk produced in China found its way to Europe. Bolts of silk apparently were strapped to the backs of camels which then plodded their way across a well-defined route via Central Asia and from there the precious (and now very expensive) goods found their way to the markets of Constantinople and Venice. It turns out that the concept is ridiculous and not just overly romantic. Firstly, no such ‘road’ existed; indeed no such route ever did. In fact, there were many routes overland from East to West. And if one thinks about the actual cost of strapping necessarily small quantities of goods to the backs of camels and horses, one might come to realise, especially if one has some economics training, that the far cheaper way of sending anything, particularly anything in any great quantity, is by ship. The problem of course is that remnants of overland staging posts in the form of bricks and mortar no matter how ruined stay around for hundreds and even thousands of years as proof of their existence. Wooden sailing ships generally do not. And so our understanding of history has become distorted and skewed in favour of the physical. Archaeologists tap the physical, they do not unearth concepts; they find evidence for commerce but they don’t find commerce itself, and for many, that is rather limiting.

What is particularly refreshing about the British Museum’s Silk Roads exhibition is that not only does it acknowledge that there was not one road but many routes (the Museum’s use of the term ‘Silk Roads’ is a misnomer but probably necessary for marketing purposes, otherwise the general public, fed on a diet of silk road romanticism for decades, would not have understood what the exhibition is about), it also acknowledges that shipping was a method of getting goods – including silk – from China and elsewhere in Asia to the markets in the west. And so, the exhibition becomes not about the ‘Silk Road’ but about (almost) the entirety of early trade between Asia and the West in all its guises and modes, and as such it is an exhibition about trade, business and economics. The cultural artefacts on display serve as circumstantial evidence for what economists have known all along.

And so what is on display? Having decided that the exhibition isn’t really about the silk ‘road’ has given the curators the freedom to include all manner of surprising and ostensibly extraneous objects and in part, that is what makes this exhibition such a delight – as you wonder from one case to another, myriad unexpected and seemingly unrelated objects pop up, all contributing to a story that is even wider than might have been suggested by the grand but nonetheless spurious notion of a silk road.

In terms of the exhibition itself and how it is arranged, there is a pleasing, meandering route – you flow through the exhibition a bit like you are on a riverine trade route yourself. There are large, helpful summarising slogans on the walls which appear somewhat fascist from a design point of view, and the objects are not too crowded. However, many of the cases are too low and clearly there has been significant economising on how the objects are displayed. For example, one gold bowl from 8th century Romania, that is decorated on both sides, should have been suspended upright so that both sides could be seen. Instead it lays down flat and the curators have made do with a photograph to show you the interior – what you otherwise cannot see – which is absurd when the item is sitting there and could simply have been displayed properly. Perhaps a photograph is cheaper than a proper display stand.

In short, very few of the items shown actually have anything to do with silk, so the title of the exhibition is a pity but again, probably one borne of necessity, because (rightly) there’s not too much about silk, and the ‘roads’ simply did not exist. The content though is marvellous.

The exhibition is accompanied by a well-illustrated, 300-page catalogue.

Above: The exhibition opens with this small bronze Buddha dating to around the 6th century and probably from the Swat Valley in what is now Pakistan. The very exciting thing for art historians is that it was unearthed in Sweden. Most economic historians will be less surprised.

Above: A 7th century outer container for a reliquary from Korea, offered as evidence of the spread eastwards of Buddhism. The exhibition draws on a range of eclectic objects to tell a big story.

Above: A 10th century memorial banner for a Uygher cleric. The link to trade is spurious but it’s an interesting item.

Above: An 11th century Fatamid rock crystal carving of an elephant. Most rock crystal used by the Fatamids was imported from Madagascar, underlining the scope of this exhibition and the theme of early trade more generally.

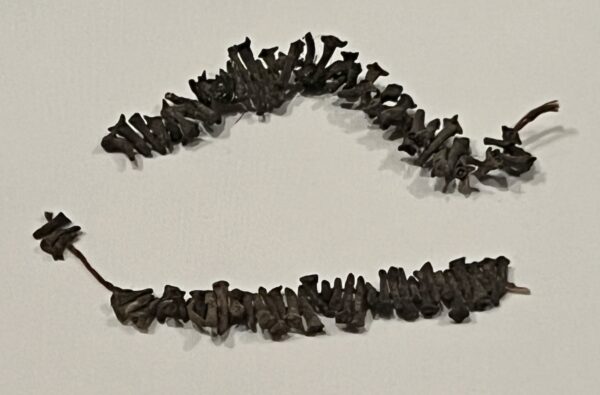

Above: Probably one of the most interesting objects in the exhibition – two strings of dried cloves from what today is Indonesia but from 5th century Egypt where they were excavated at Qaw el-Kebir. This humble display tells more about trade than almost anything else in the exhibition and has little to do with conventional notions of there being a silk ‘road’. They would have arrived by ship.

______________

Receive our regular catalogues of new stock, provenanced from old UK collections & related sources.

See our entire catalogue of available items with full search function.

______________