Enquiry about object: 3829

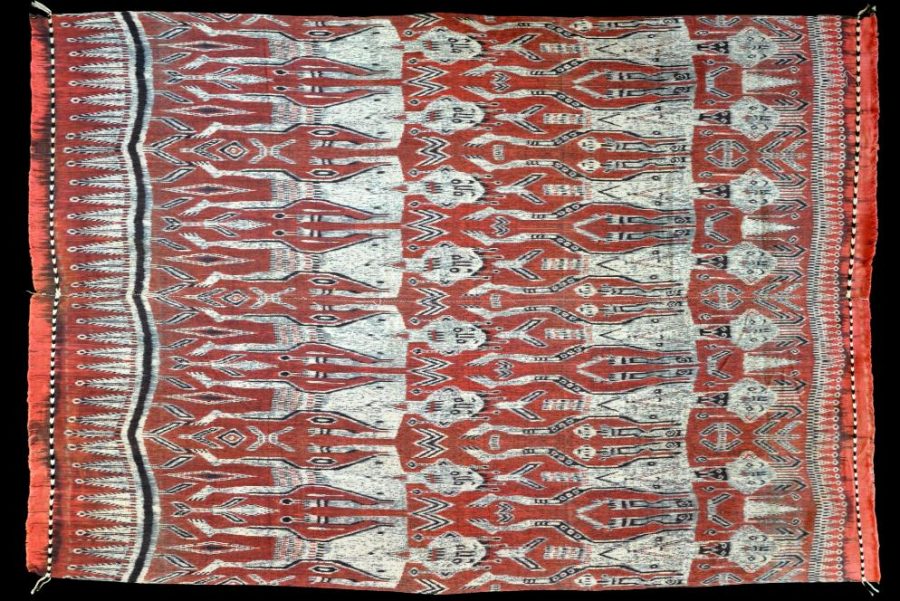

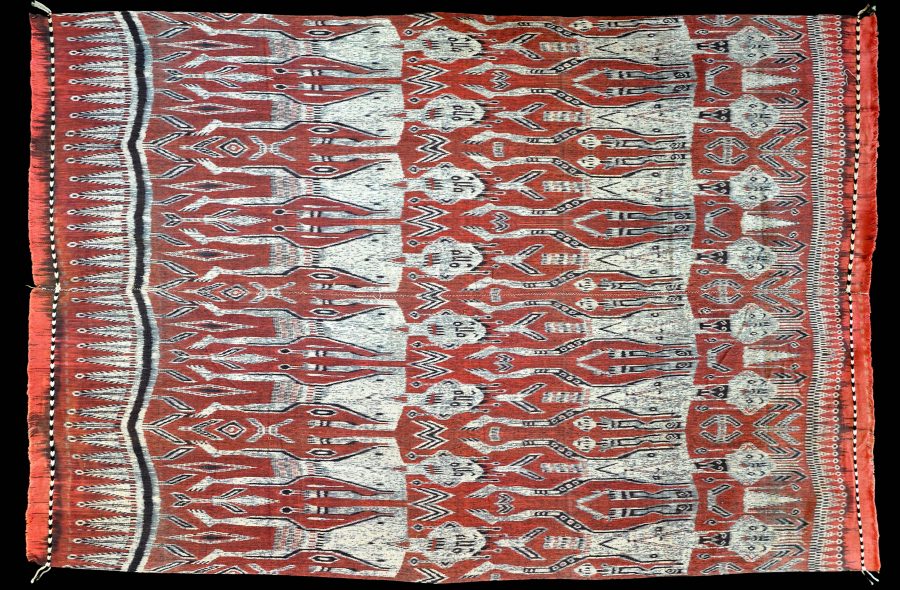

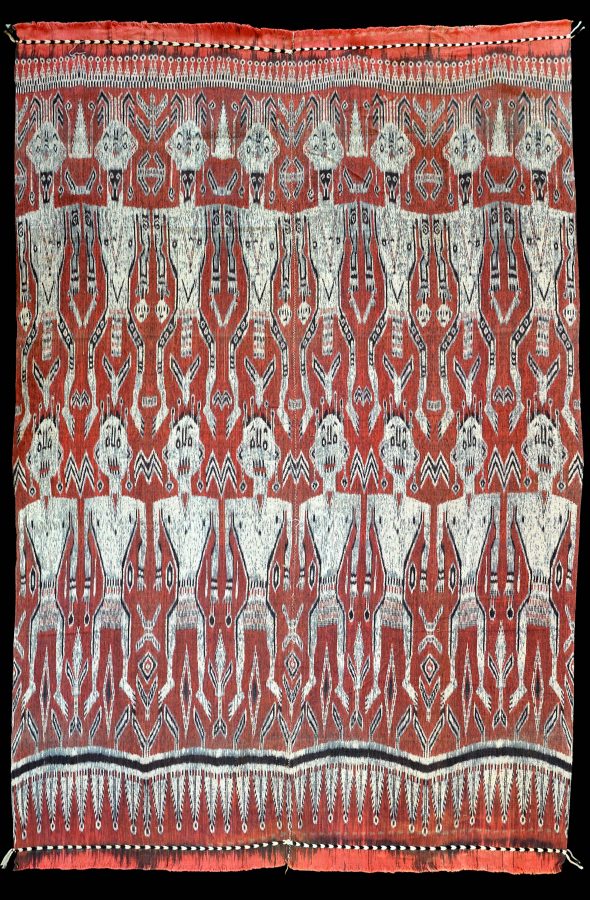

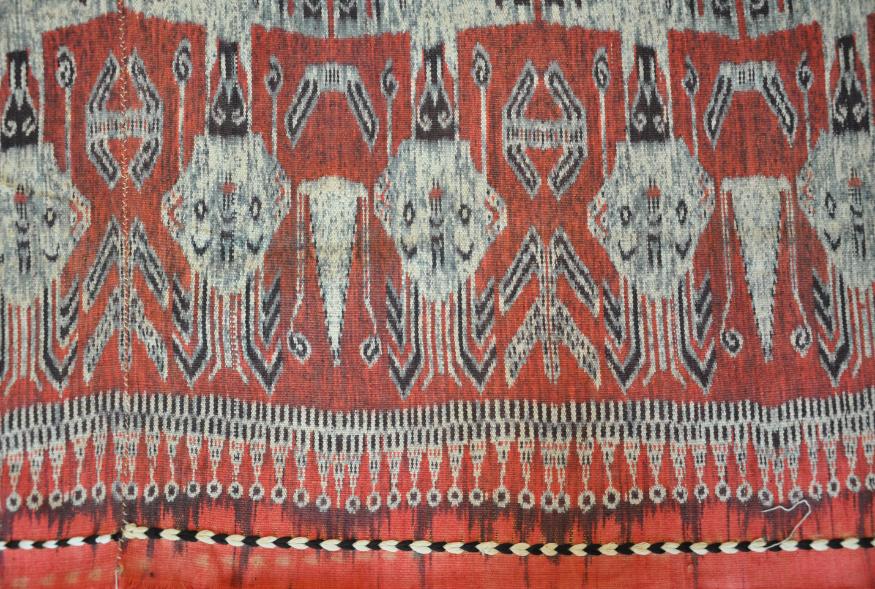

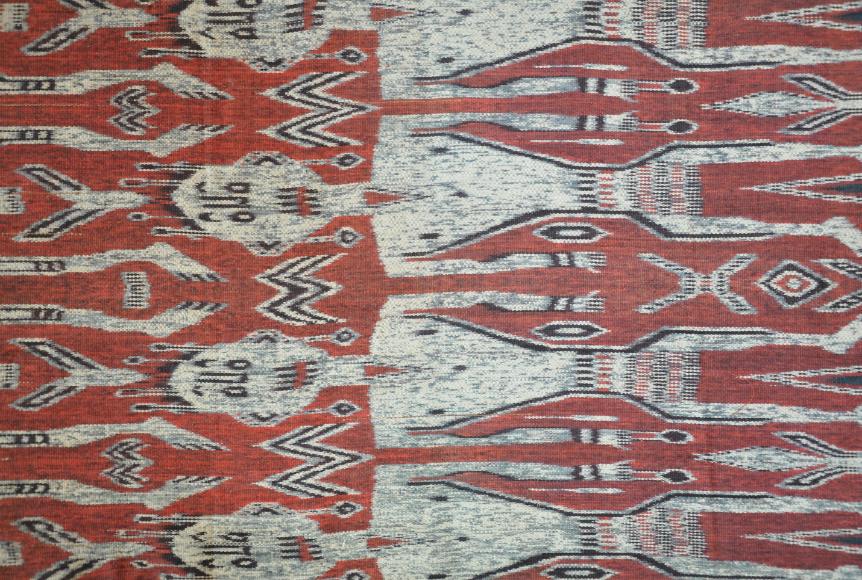

Ceremonial Borneo Iban Pua Textile

Iban Dayak People, Sarawak, Borneo, Malaysia circa 1940

length: 198cm, width: 131cm

Provenance

Acquired in the UK, from the estate collection of Dr George Yuille Caldwell (1924-2016). Dr Caldwell, an English-born physician moved to Singapore in the 1950s, from where he built up a collection of mostly Borneo-related textiles and other ethnographica.

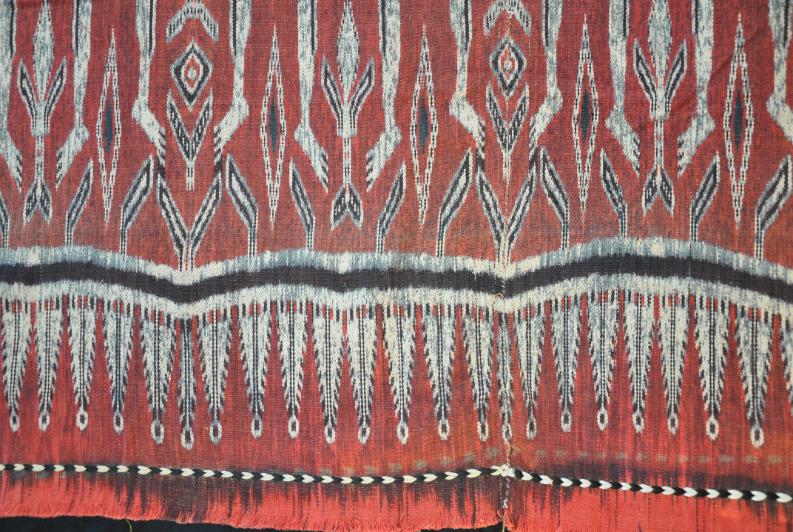

This pua comprises two hand-woven panels of machine-spun cotton hand-stitched together down the middle. The supplementary weft pattern comprises two rows of Iban warriors. Each of the top row brandishes decapitated heads. The ends of the textile are braided.

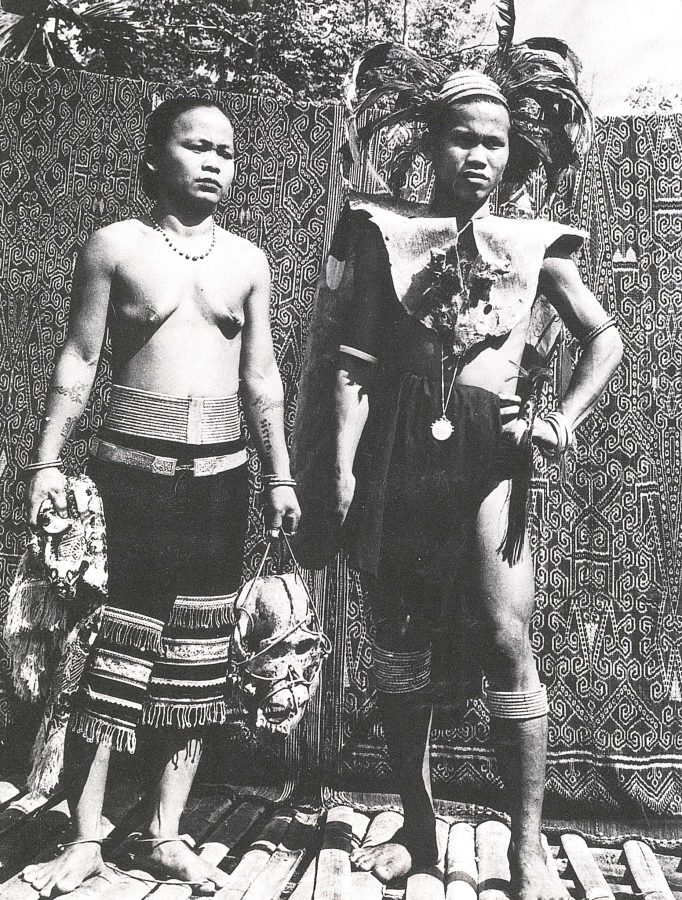

This textile belongs to a group of large blanket-like hangings known aspua. Mostly,pua cloths are patterned with warp ikat patterns in earthy deep reds, browns, beige and blue-black colours. The pua are believed by the Iban to communicate with the spirit world and to protect individuals during times of danger and crisis (Gittinger, 2005, p. 102). Pua were used at various harvest-and life-cycle rituals known as gawai. Villagers would gather at a longhouse for several days of feasting during which the gods were invoked to leave their heavenly abode and visit the earth. The pua were hung about and near the longhouse to greet the arriving gods who would take pleasure in seeing the large textiles. The gods would respond by bestowing blessings on the festival givers and attendees. Pua could also be used to create a temporary shrine to enclose ritual objects. Certain puas might have been hoisted as a signal that a longhouse was in mourning, or hung to assist with healing and sickness rituals.

Woman were responsible for weaving the pua. But the task was a perilous one. The weaver was at the interface of the physical and spiritual worlds and the supernatural powers potentially endangered the weaver and also empowered her patters. According to Gittinger (2005, p. 105), a woman may receive inspiration for a pua pattern in a dream inspired by the spirits. She must follow such commands or risk severe physical or mental malaise. Those women deemed to be the best weavers were honoured the most in the community for it was felt that their connections to the spirit world were the most intense.

The patterns on pua cloths relate to their intended use. And generally, the older a cloth, the more sacred or ‘powerful’ it was considered to be. According to Gittinger (2005, p. 102), ‘Most Iban textiles challenge the eye. Kaleidescopic patterns hover just at the edge of comprehension. Crocodile, snake, and anthropomorphic forms may emerge from the welter of patterning, but just as often there is a structured tangle of hooks and coils that defies labelling. This is a language of design unique to the Iban of Sarawak and the Iban-related peoples of Kalimantan – the Kantu’ and Mualang. It is a vocabulary to delight the gods and to invite them and their blessings into this world.’

This textile is in excellent condition. There are no repairs and no insect damage.

The last three images show pua textiles in use during the early 20th century.

References

Gavin, T., The Women’s Warpath: Iban Ritual Fabrics from Borneo, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1996.

Gittinger, M., Textiles for this World and Beyond: Treasures from Insular Southeast Asia, Scala, 2005.

Haddon, A.C., & L.E. Start, Iban Sea Dayak Fabrics and their Patterns, Ruth Bean, 1982 (reprint of 1936 edition).