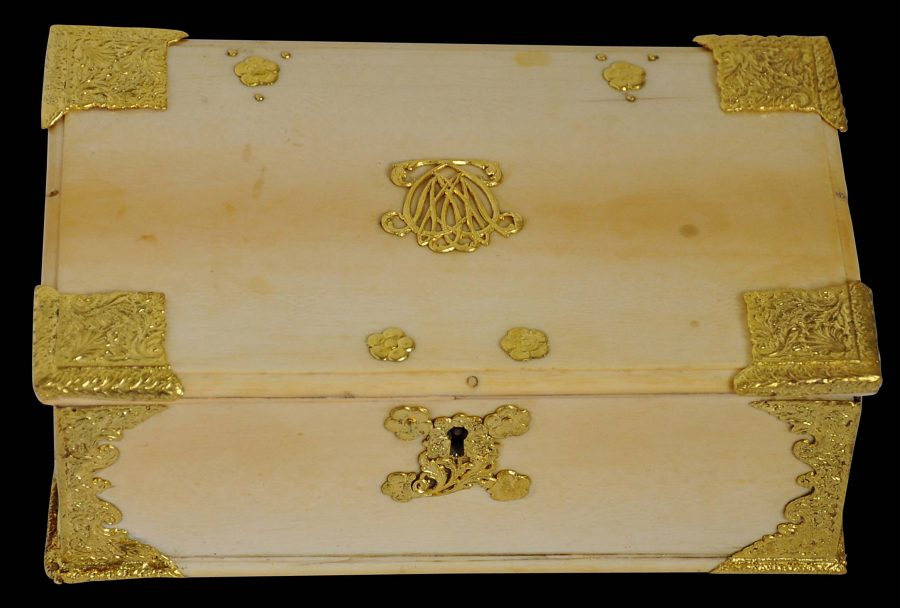

This fine Dutch colonial betel or sirih box is from eighteenth century Batavia in the Dutch East Indies, and is composed of ivory sheets fixed with ivory pegs and decorated with chased, solid gold mounts. (All sides including the base are of ivory sheets.) Ivory betel boxes are relatively rare. More typically, they are made of wood. Ivory boxes with gold mounts are even rarer. Eighteenth century inventories mention the existence of numerous ivory and gold boxes but according to Veenendaal (2014, p. 121) ‘only one example of an ivory betel box with gold fittings is now extant.’ Together with the example here, there are now two.

Possibly it was made for a Dutch colonial administrator or his wife – the Dutch took up the local habit of chewing betel in the Dutch East Indies during the 18th century. The top of the lid has a central monogram in gold which appears to show the initials ‘MM’.

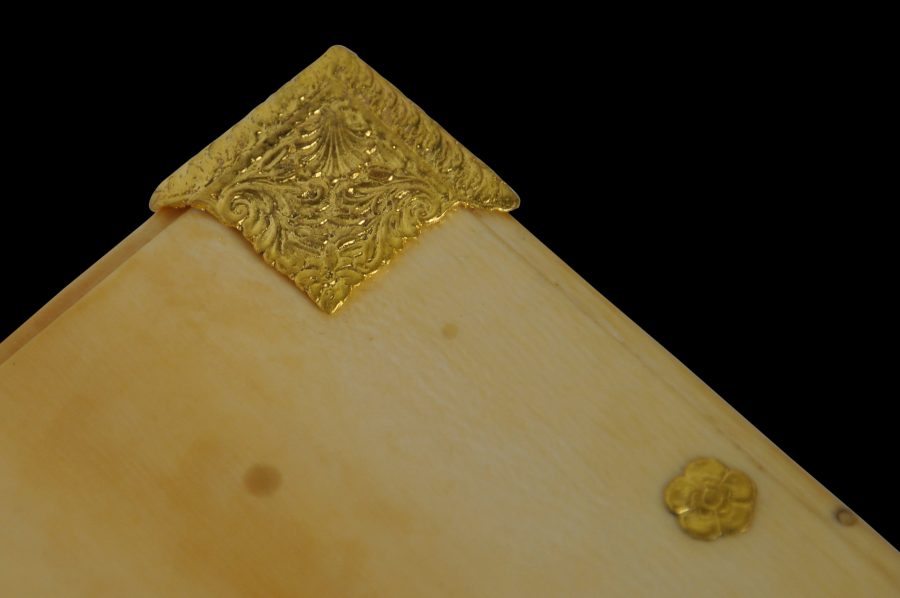

The box has chased gold floral plaques designed to cover the screws used in its construction. There are also chased gold corner mounts, hinge flanges, and a gold key escutcheon.

Fine, engraved gold hinge flanges are attached to the inside of the box. These attach the lid or cover to the base.

The original gold lock is in place. The key no longer is present however.

The box does not have feet; nor are there any signs that it ever did have feet.

The Javanese habit of chewing betel was adopted by the local Dutch and exquisite boxes to hold the nut, the betel leaf and the other accompaniments were commissioned by the Dutch. The Dutch realised early on how important betel was to the indigenous people and how it was an essential part of hospitality including with the indigenous rulers. They quickly incorporated betel use with their dealings with local elites. Paintings that show the wives of Dutchmen at the time often show betel boxes prominently displayed. One such seventeenth century painting by J.J. Coeman which today hangs in the Rijksmuseum shows Batavia’s Cornelia van Nieuwenroode with her husband Pieter Cnoll and two of their nine daughters, one of who is shown holding a jewelled betel box (Gelman Taylor, 2009, p. 42).

The fashion for luxurious betel accoutrements and other finery saw the governor-general in Batavia Jacob Mossel issue a decree in 1754 stating that only the wives and widows of the governor-general, the director-general, members of the Council of the Indies and president of the Justice Council were permitted to

use gold or silver betel boxes adorned with precious stones, (Zandvlieyt, 2002, p. 206).

In terms of condition of the example here, the ivory has a superb honeyed patina associated with significant age and use. There is little evident warping. The lid fits relatively well and evenly. There are minor shrinkage-related cracks to the base; these are old and stable. The gold has been cleaned and several sections of gold have been repaired. There are no apparent maker’s marks to the gold.

References

Eliens, T.M., Silver from Batavia/Zilver uit Batavia, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag/W Books, 2012.

Krohn D.L. & P.N. Miller (eds.), Dutch New York Between East and West: The World of Margrieta van Varick, Bard Graduate Center/The New York Historical Society/Yale University Press, 2009.

Parthesius, R., Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595-1660, Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

Tchakaloff, T.N. et al, La Route des Indes – Les Indes et L’Europe: Echanges Artistiques et Heritage Commun 1650-1850, Somagy Editions d’Art, 1998.

Veenendaal, J., Furniture from Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India During the Dutch Period, Foundation Volkenkundig Museum Nusantara, 1985.

Veenendaal, J., Asian Art and the Dutch Taste, Waanders Uitgevers Zwolle, 2014.

Voskuil-Groenewegen, S.M. et al,Zilver uit de tijd van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, Waanders Uitgevers, 1998.