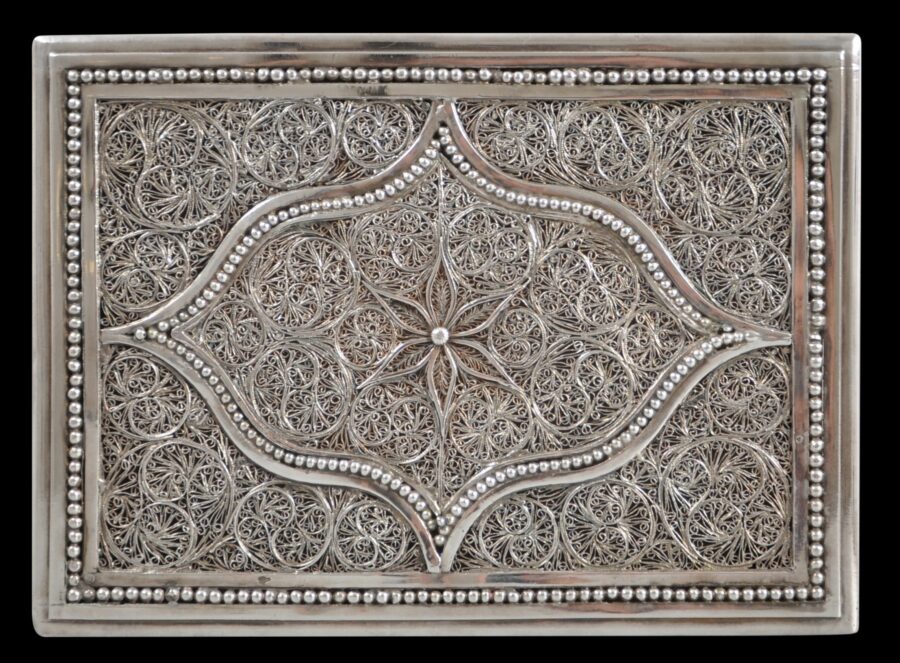

This extraordinary silver box from Dutch colonial Batavia (now Jakarta) or Sumatra, and formerly in the collection of Queen Juliana of The Netherlands, comprises panels of fine, dense silver filigree within borders of flat silver ribs and fine silver beads.

At the centre of the hinged lid and also at the centre of the back panel are motifs based on the star anise (Illicium verum), a spice used widely in Indonesian, Malaysian and Chinese cooking, and grown in commercial quantities in Indonesia for hundreds of years. The use of this motif is highly instructive: it further suggests Dutch colonial provenance linked to the Dutch East Indies. It is also evocative – the Indies were known, in part, as the Spice Islands, and is why they were so important to Europe in the 16th-18th centuries. Control of these islands meant cornering most of the world’s spice trade.

The remainder of the filigree comprises tight curls, and curls within curls – some of the finest filigree silver work that we have seen. Indeed, few items of Batavian filigree silver published are as extensive in their use of filigree, or as fine.

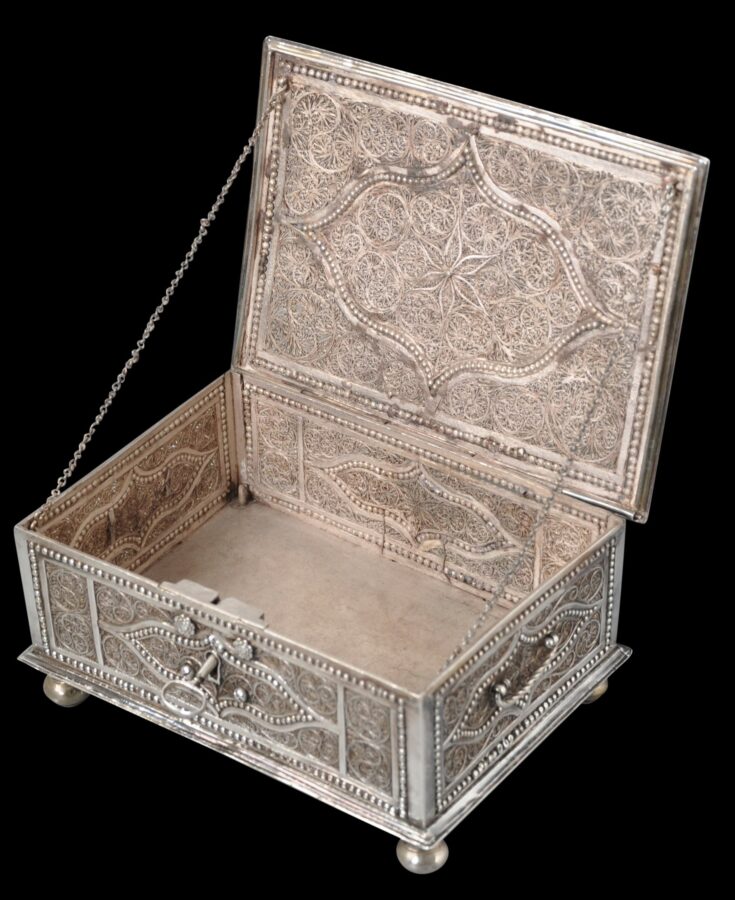

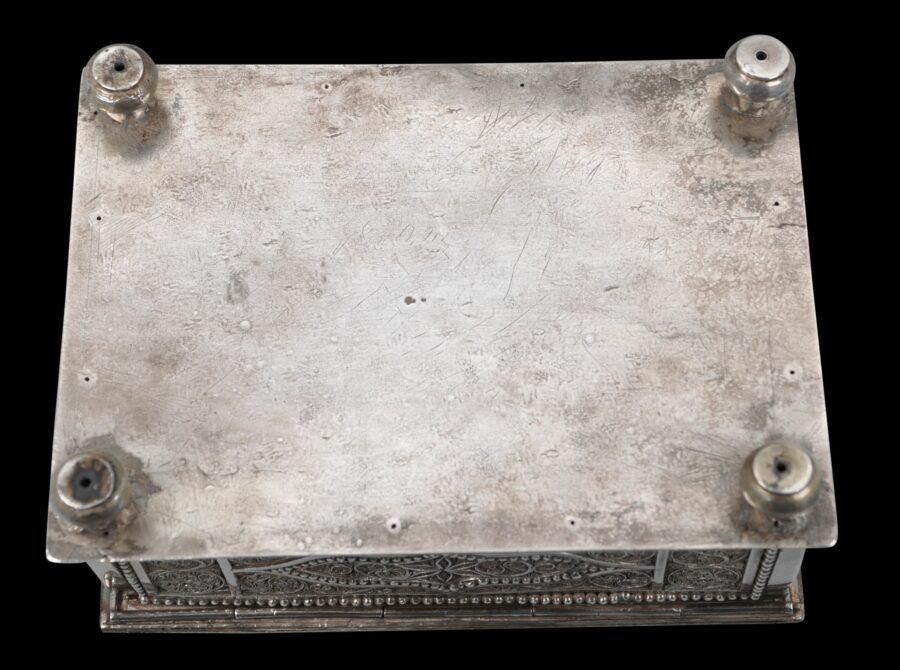

The box sits on four spherical feet. It has an elegant twist handle on each side. The lid lifts up and is supported by an internal silver chain on each side of the box. The base of the box is of hammered sheet silver. The original lock and key are still present. (The lock though no longer functions readily.)

The box is of the proportions of a betel box used by both the aristocratic Javanese and senior Dutch colonial administrators and their wives during the 18th century. It does not have internal dividers that are commonly found in betel boxes of the type of the period (nor are there signs of there having been any) , so the box might have been intended to serve as a jewellery box.

The Javanese habit of chewing betel was adopted by the local Dutch and exquisite boxes to hold the nut, the betel leaf and the other accompaniments were commissioned by the Dutch. The Dutch realised early on how important betel was to the indigenous people and how it was an essential part of hospitality including with the indigenous rulers. They quickly incorporated betel use with their dealings with local elites. Paintings that show the wives of Dutchmen at the time often show betel boxes prominently displayed. One such 17th century painting by J.J. Coeman which today hangs in the Rijksmuseum shows Batavia’s Cornelia van Nieuwenroode with her husband Pieter Cnoll and two of their nine daughters, one of who is shown holding a jewelled betel box (Gelman Taylor, 2009, p. 42).

The fashion for luxurious betel accoutrements and other finery saw the governor-general in Batavia Jacob Mossel issue a decree in 1754 stating that only the wives and widows of the governor-general, the director-general, members of the Council of the Indies and president of the Justice Council were permitted to use gold or silver betel boxes adorned with precious stones, (Zandvlieyt, 2002, p. 206).

The filigree work on this box suggests that it has come from or been made by a Malay artisan who came from Sumatra. Such filigree work was known in Batavia at the time as ‘Westcust werk’ (Veenendaal, 1995, p. 88). The floral silver rivet heads used on the front of this box are not unlike those used on a box illustrated in Voskuil-Groenewegen (1998, p. 56), which is attributed to the early 18th century Batavia.

This box came from the estate of The Netherlands’ Queen Juliana and presumably was presented to the Dutch royal family when the Dutch East VOC ruled Batavia. It is without maker’s marks but it does have Dutch import marks to the lid and base in the form of an axe stamp denoting at least 0.833 fineness and used on items that were deemed to be antique at the time of being presented for assaying. (This mark was used between 1814 and 1953.)

The box is important for its fineness, royal Dutch provenance, and because of the star anise motifs employed, linking it to the Dutch East Indies.

This actual box is illustrated in Malay Silver & Gold: Courtly Splendour from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei & Thailand (by Michael Backman, published by River Books, forthcoming).

References

Gelman Taylor, J., The Social World of Batavia: Europeans and Eurasians in Colonial Indonesia, 2nd ed., The University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

Haags Gemeentemuseum, V.O.C. – Zilver: Zilver uit de periode van de Verenigde Oostinische Compagnie 17de en 18de eeuw, 1983.

Tchakaloff, T.N. et al, La Route des Indes – Les Indes et L’Europe: Echanges Artistiques et Heritage Commun 1650-1850, Somagy Editions d’Art, 1998.

Voskuil-Groenewegen, S.M. et al, Zilver uit de tijd van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, Waanders Uitgevers, 1998.

Zandvlieyt, K. et al, The Dutch Encounter with Asia 1600-1950, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2002.