Enquiry about object: 6773

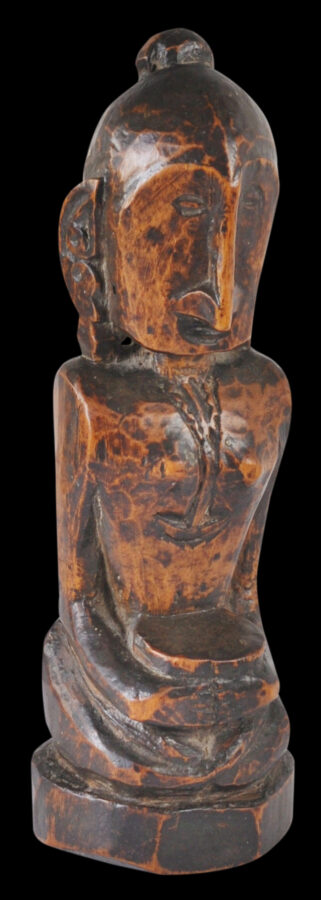

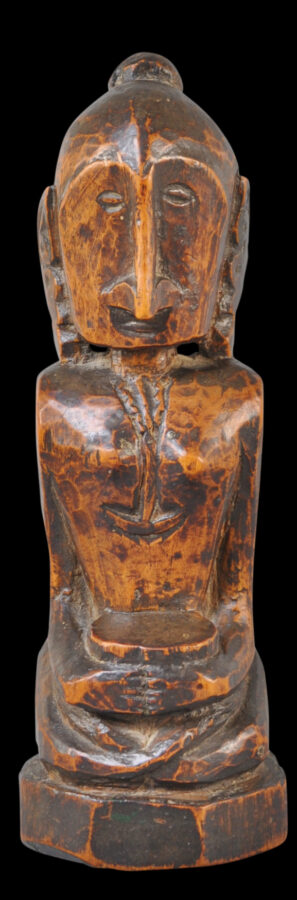

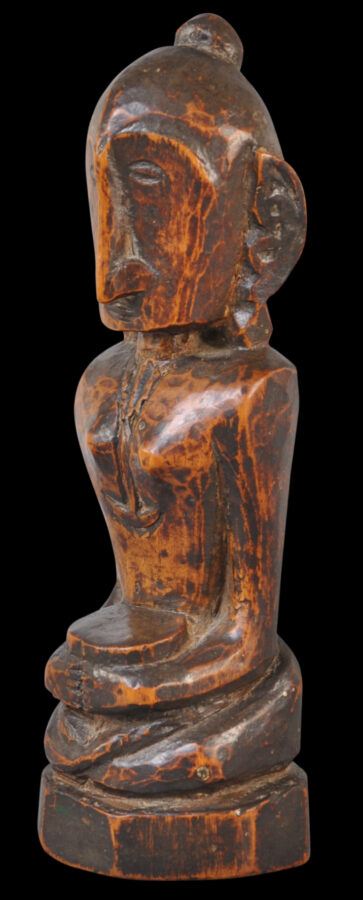

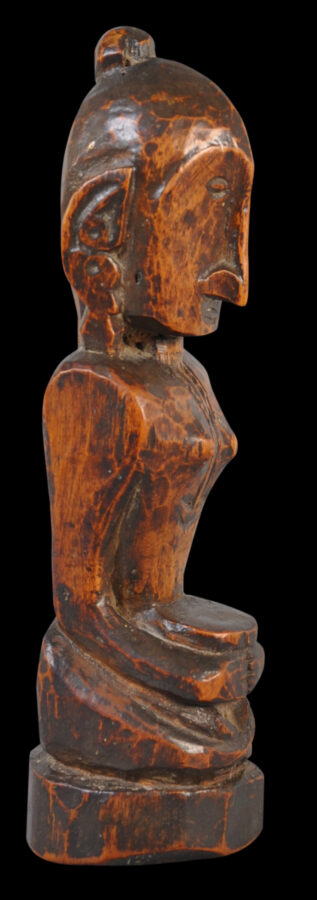

Exceptional, Early Tanimbar Ancestor Figure

Tanimbar, Southeast Moluccas, Eastern Indonesia 18th century

height: 16.4cm, width: 5.4cm, depth: 4.5cm

Provenance

Private Collection, Northern England; acquired by the previous owners from an antiques fair, York, England, circa 1980

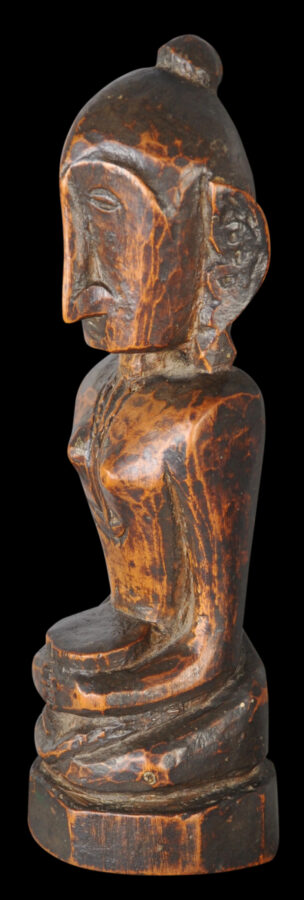

This wooden statuette is in the tradition of the yene or iene ancestor figurines from Leti, in the Moluccas in Eastern Indonesia, although this example is from nearby Tanimbar Island. It has the most extraordinary wear and varying darkened patina; its contours much softened from ritual handling. A dating of at least the 18th century seems likely. It appears significantly earlier than most known examples in museum collections.

The figure is that of a female. Most such statuettes are of males; females are rarer. The legs are crossed and under the body in what is known as the bersila position. (Male statuettes almost always are carved in a squatting position with pulled-up knees). The arms rest on the thighs with the hands together. A broad bowl sometimes said to be for betel nut or perhaps for small offerings of actual slices of betel nut, rests over the lap. The care taken to indicate the sex of the figure is typical of Eastern Indonesian artwork, and on Tanimbar, all objects and even activities were regarded as having a gender. ‘Male’ objects tended to be heavy; ‘female’ objects were lighter. The wood used to carve this statuette is noticeably light, probably Beach Cordia wood (Cordia subcordata).

The figure sits on a roughly octagonal platform. It has an elongated body and arms, broad shoulders, small but obvious breasts, an oversized head with a long aquiline nose, almond-shaped eyes, and a vertically-flat back. The hair is pulled to the top of the head in a bun, there are elaborate, long pendant earrings and other ear ornaments on the upper ears, and a long necklace with a large, crescent pendant. Large items of jewellery, usually in gold for the nobility or higher classes, were not unusual. Indeed, the importance of ancestral jewellery was such that the form of the jewellery carved onto ancestor statues usually is immediately identifiable. Richter & Carpenter (2012, p. 50) illustrate three crescent-shaped gold pendants that they attribute to Leti and to which they ascribe a dating of 17th-18th century.

Shortly after someone passed away, the Tanimbarese and Leti people would usually carve a statuette either as a stand-in for the deceased or as a temporary shelter for the ancestral ‘shadow’ (nitu) and as a way or retaining contact with the dead relative. The statuette would then be used to call upon the deceased for assistance in matters relating to warfare, hunting or fertility. The example here being female and with much wear most probably was used as a fertility cult object that was stroked and caressed as a fertility talisman. The statuettes generally were kept in the eaves of houses.

There is a quality and obvious age and patina to the statue that is reminiscent of an ivory example in the Liefkes Collection, held in the National Museum of Ethnology (Leiden, Netherlands) and illustrated in Brinkgreve & Stuart-Fox (2013, p. 293). The Liefkes example was collected by a Dutch missionary in Tanimbar in the early 20th century but is dated to 1650-1700. An ancestor figure of related form attributed to Tanimbar and in the National Museum of Indonesia is illustrated in Taylor & Aragon (1991, p. 242).

Until recently, the figure here was held in a private collection in northern England and was believed to be ‘probably African.’ It was paired with another example shown in the last image below. Both were acquired by the previous owners in England at an antiques fair more than forty years ago. The statuettes’ whereabouts prior to that is not known.

Some Tanimbar and Leti statuettes found in Europe are likely to be of significant age. The Portuguese ‘discovered’ the islands in the 16th century and the Dutch were trading directly with Tanimbar in the 17th century. And by the 20th century, Christianity made substantial inroads into the area, so that sometimes ancestral figures no longer were wanted and were collected by missionaries and brought back to Europe. In any event, the statuettes were only ever considered to be temporary shelters for the ‘shadows’ of the ancestors, and this might explain why the Tanimbarese felt able to barter them for goods that European traders might have had.

Overall, the example here is among the finest we have seen published or otherwise, and its patina suggests it to be among the oldest. It is in fine condition. There are no repairs. There is an old shrinkage crack on the lower back of the piece as might be expected. This is stable and has no material impact on the piece.

References

Barbier, J.P., Indonesian Primitive Art, Dallas Museum of Art, 1984.

Brinkgreve, F., & D.J. Stuart-Fox (eds), Living with Indonesian Art: The Frits Liefkes Collection, Rijksmuseum Volkenkunde, 2013.

Capistrano-Baker, F.H., Art of Island Southeast Asia: The Fred and Rita Richman Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994.

de Jonge, N., & T. van Dijk, Forgotten Islands of Indonesia: The Art & Culture of the Southeast Moluccas, Periplus Editions, 1995.

Kuhnt-Saptodewo, S., et al, Maluku: Sharing Cultural Memory, Museum fur Volker Kunde, 2012.

Maxwell, R., Life, Death & Magic: 2000 Years of Southeast Asian Ancestral Art, National Gallery of Australia, 2010.

Richter, A., & B. Carpenter, Gold Jewellery of the Indonesian Archipelago, Editions Didier Millet, 2012.

Schefold, R. (ed.), Eyes of the Ancestors: The Arts of Island Southeast Asia at the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Museum of Art/Yale University Press, 2013.

Schoffel, A., Arts Primitifs de l’Asie du Sud-Est (Assam, Sumatra, Borneo, Philippines): Collection Alain Schoffel, Alain et Francoise Chaffin, 1981.

Tanudirjo, D.A., et al, Ancestors and Rituals, Snoeck, 2017.

Taylor, P.M. & L.V. Aragon, Beyond the Java Sea: Art of Indonesia’s Outer Islands, National Museum of Natural History/Harry N. Abrams, Inc,1991.

Wentholt, A., Nusantara: Highlights from Museum Nusantara Delft, C. Zwartenkot Art Books, 2014.