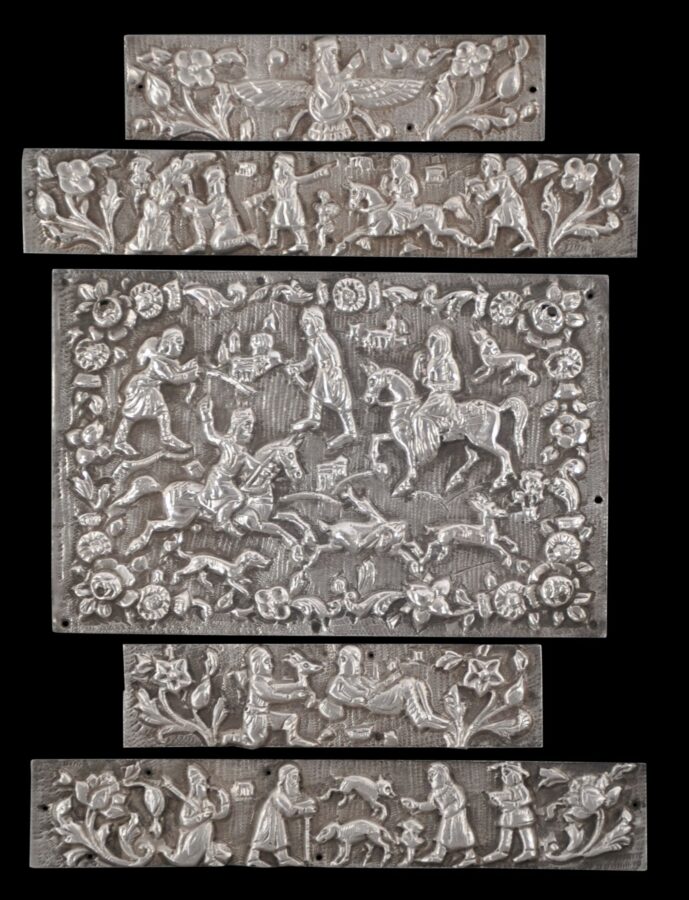

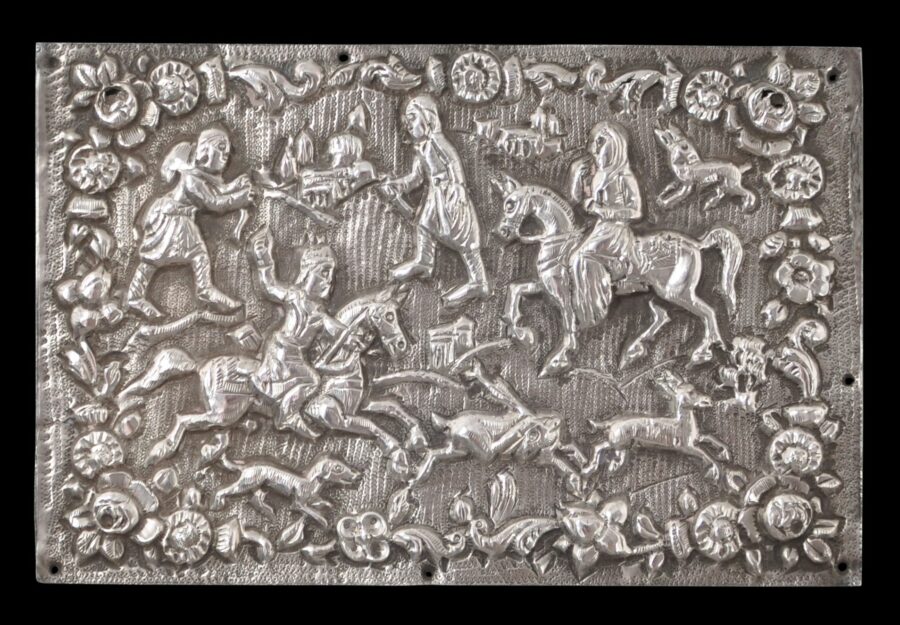

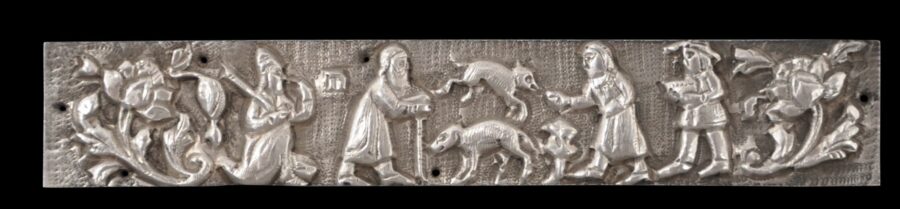

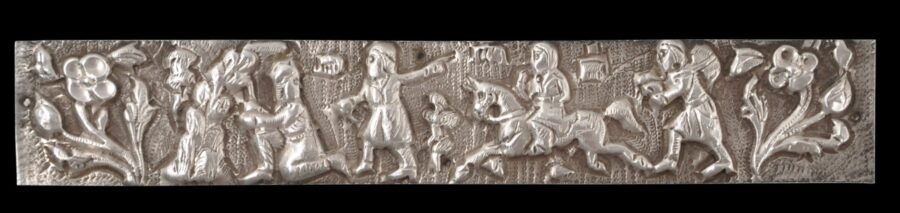

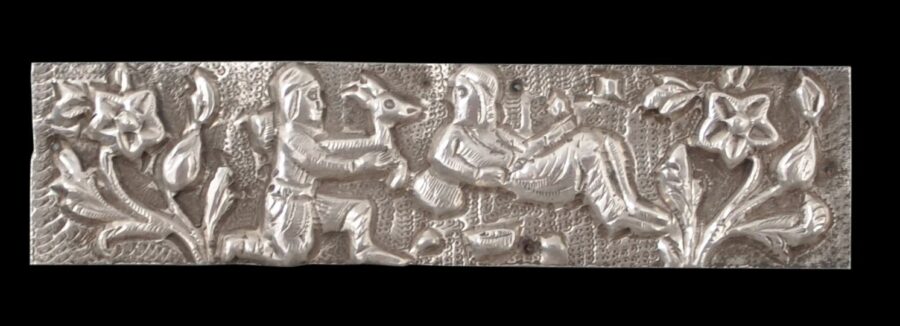

This rare set of five silver plaques are repoussed and chased with Zoroastrian religious scenes and would have been made in Bombay for the local Parsi (Parsee) community.

Possibly the plaques were commissioned to be attached to the doors leading to a room of particular religious significance in a Parsi fire temple, quite possibly the prayer hall or fire chamber. Each of the plaques has been drilled with small holes to allow for fixing to a wall or door. Stewart (2013, p. 212) shows a serving priest (boyvara) tending the sacred fire in the fire chamber of a fire temple and affixed to the double doors leading to the chamber are a series of plaques similar to the examples here.

Each plaque shows various Zoroastrian scenes and motifs, against fine ring-mat backgrounds. The winged Parsi deity Ahura Mazda is represented prominently. The scenes are bordered by flowers, in many cases, roses, which often appear on silverwork made for the Bombay Parsis.

By the early twentieth century, there were three main Parsi silver shops in Bombay that specialised in making Parsee-themed ritual items for the local community. Many other silver items were imported from southern China where silversmiths made items for export worldwide (Cama, 1998).

Parsis subscribe to Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest living religions. Darius was crowned king of Persia in 522 BC, and was the first of the Achaemenid kings to be confirmed as a true follower of Zoroaster. Ahura Mazda, proclaimed by Zoroaster as God, was mentioned and celebrated as Creator in many of Darius’ speeches.

Under the kings of the Achaemenian line, the religion became one of the great religions of the ancient East. But it shared the fate of the Persian monarchy, it was shattered, though not overthrown, by the conquest of Alexander and it fell into neglect. With the Arab conquest in the seventh century came Islam and Zoroastrianism was vigorously repressed. A group of Zoroastrians fled in 936AD to Gujurat in India. By the 17th century, most had moved to Bombay, with smaller communities in Karachi and Rangoon. (Later small communities existed in Singapore and Hong Kong.) The Bombay community today is the world’s largest, far exceeding the relative handful of Zoroastrians that remain in Iran.

Zoroastrianism teaches the importance of the elements, particularly fire. Zoroastrian pilgrims had for example come from Persia during the Middle Ages onwards to erect temples and worship the then mysterious fire that shot out of the earth in certain parts of Azerbaijan, fuelled by underground wells of natural gas. A belief in the existence of angels is another important Parsee belief. Angels guide individuals and events.

Each Parsi fire temple has a central, sacred flame that is never allowed to go out. (Bombay/Mumbai has around fifty fire temples.) Traditionally, the bodies of dead Parsis are laid out in so called ‘Towers of Silence’ and crows are then allowed to feed on them. This is preferred because it is considered that cremation would ‘pollute’ fire, and burial would ‘pollute’ the earth. In Bombay, the principal Towers of Silence are adjacent to city’s so-called ‘Hanging Gardens’.

Today, probably there are fewer than 140,000 Parsis or Zoroastrians worldwide. About 80,000 live in Mumbai/Bombay, a city of 14 million people. Another 6,000 live in Karachi in Pakistan.

Like Europe’s Jewish communities or the Chinese of Southeast Asia, the Parsis of India and Pakistan are a distinct but exceptionally successful commercial minority. By the nineteenth century, Bombay’s Parsee families dominated the city’s commercial sector, particularly in spinning and dyeing and banking.

Wealth from these activities was put into property so that by 1855, it was estimated that Parsi families owned about half of the island of Bombay. Today, India’s most prominent Parsee family is the Tata Family, founders and owners of India’s most prominent conglomerate the Tata Group.

Well off though they are as a community, the Parsis are dying out. It has been estimated that a thousand Parsis die each year in Mumbai, but only 300-400 are born. Today, one in five Mumbai Parsees is aged 65 or more. In 1901 the figure was one in fifty. Low birth rates are the main factor. Probably no Parsees remain in Burma today.

Nonetheless, many vestiges of the Parsis’ contribution to commerce in South and East Asia remain. Apart from India’s giant Tata Group, smaller examples can be seen: small change offices in Hong Kong are known locally as ‘schroffs’ after a common Parsee surname, and in Singapore the road that runs alongside that country’s finance ministry is known as Parsi Road.

References

Cama, S., ‘Parsi crafts: Gifts from Magi’, UNESCO Power of Creativity Magazine, Vol. 2, August 2008.

Framjee, D., The Parsees: Their History, Manners, Customs and Religion, Asian Education Services, 2006 (first published in 1858.)

Godrej, P.J. & F. Punthakey Mistree, A Zoroastrian Tapestry: Art, Religion & Culture, Mapin Publishing, 2002.

Stewart, S. (ed.), The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination, SOAS, 2013.