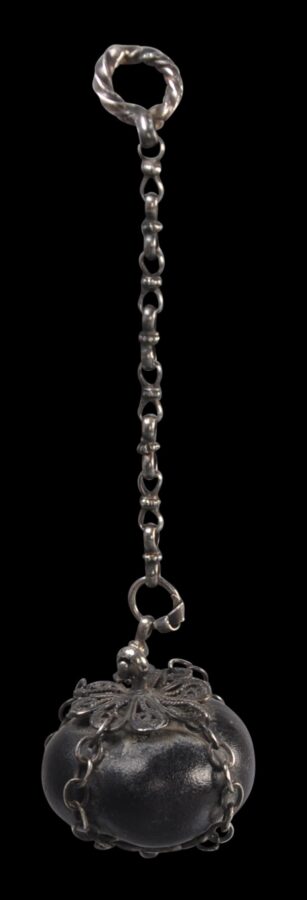

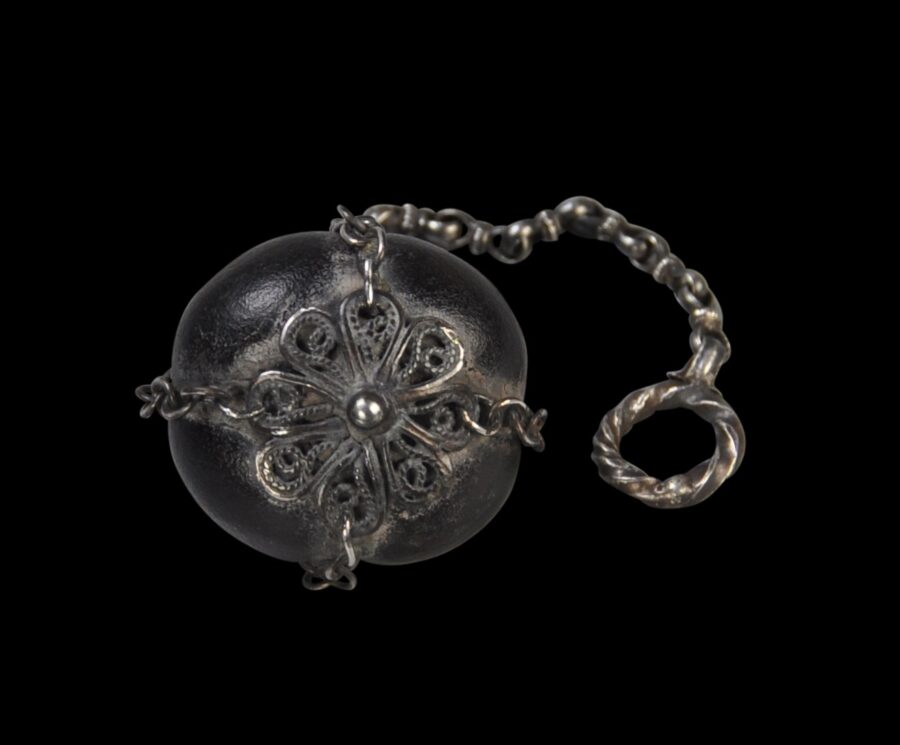

This unusual bezoar stone has fine, silver filigree mounts, is encased in silver chains, and is suspended from one long silver chain. It was designed to be jiggled in a cup of liquid much like a tea bag so that it would impart its medicinal properties to the liquid which could then be drunk. It is also possible that it was designed to be worn from a chain around the neck – some bezoar stones were not intended to be consumed orally in anyway but were worn as protective amulets. Lowe (2024, p. 261) tells how in the late sixteenth century bezoar stones with metal mounts were ordered in Italy from suppliers in Portugal to be worn as protection against the plague, for example.

The nature of the silver filigree and the silver chain suggests the stone and mounts have their origins either in India, most possibly in the Indo-Portuguese enclave of Goa on India’s west coast, or Ottoman Turkey, or Hormuz, where the Portuguese had a trading post.

Traditionally, bezoars were naturally occurring stones (largely comprising gallstone matter and hair) found in the digestive systems of certain animals, particularly sheep, deer and antelopes. The stones were prized for their supposed neutralising effects on poison. (The word ‘bezoar’ is thought to derive from the Persian ‘pad-zahr‘ (antidote). Artificial bezoars were made by Jesuit priests in Goa and were intended to be used in the same way as natural bezoars: ground bezoar or small chips of the stone were mixed with wine, tea or water as a medicine to counteract ailments such as epilepsy and melancholy, and as an antidote to poison, or the stone was simply allowed to rest in the liquid to impart its restorative properties.

The importance and costliness of bezoar stones meant that they were often mounted themselves with gold and silver – often in filigree as with the example here. They were often given as expensive diplomatic gifts from Asian rulers to European rulers and between European rulers. The king of Cochin sent Portugal’s Manuel I (reigned 1495-1521) a bezoar stone shortly before the Portuguese began trading there for example (Jordan, 2007, p. 91).

The example here is in excellent condition and has clear, significant age. The fact that it retains its original chain is unusual and also important for demonstrating how this stone was used.

References

Jordan, A. et al, The Heritage of Rauluchantim, Museu de Sao Roque, 1996.

Komaroff, L.et al, Gifts of the Sultan: The Arts of Giving at the Islamic Courts, LACMA/Yale University Press, 2011.

Levenson. J. (ed), Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th and 17th Centuries, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2007.

Lowe, K.J.P., Provenance and Possession: Acquisition from the Portuguese Empire in Renaissance Italy, Princeton University Press, 2024.