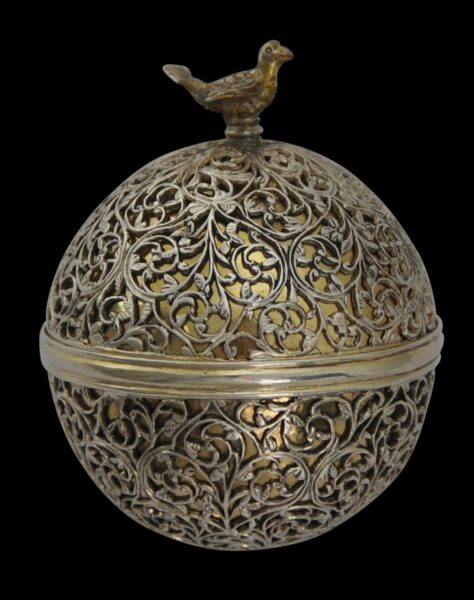

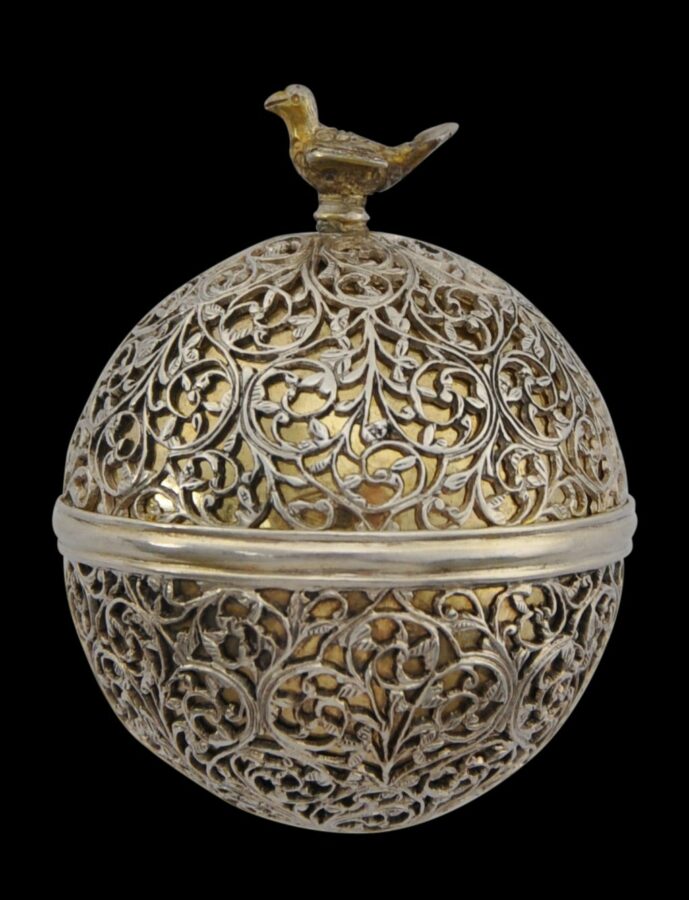

This fine spherical box was made to hold a bezoar stone. It comprises two halves, each of which consists of a fine, hand-cut, pierced, outer layer of scrolling foliate trellis work that has been engraved with cross-hatching and other patterns to provide further leafy and floral detail, and an inner layer of hammered and gilded (gold-plated) silver sheet.

Engraved, gilded flower motifs decorate each end. The mid-section comprises a raised rib that has been gilded and which conceals where the two halves comes together.

The outer layer of silver trellis work is not gilded, and this provides a fine contrast with the gilded enclosed inner layer.

The box has been topped with a gilded, solid-cast silver finial in the form of a bird. This addition is particularly Indian, and helps to confirm that box’s Indian origins.

The work on the box, with its piecing, scrolling, engraving and gilding is similar to a spectacular pair of covered bowls and tazzas that were attributed to late 17th century West India, and which were sold by Christie’s London, ‘Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds’ April 8, 2008, lot 250 (see here). The tops of the tazzas had central, engraved flower motifs that are similar to those that appear on the ends of the bezoar stone box here. It is possible, indeed, likely that this box has come from the same workshop as the Christie’s bowl and tazza sets, and most probably is the product of Muslim Gujarati craftsmen.

Engraved and pierced silver bezoar stone boxes are known in public collections. Several are held in the collection of the Wellcome Museum of Medicine, London. The Science Museum, London, has a gold bezoar stone box on a stand, its pierced and engraved scrolling decoration includes small animals (accession no. A642470). Two others, one silver, the other gold, both with contemporaneous stands, are in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (accession nos. respectively 1980.228.1, 2a,b, .3 and 2004.244a-d). An example in the British Museum has a solid-cast bird finial similar to the example here.

The example currently displayed in the British Museum with a bird finial.

The well-known English collector, Horace Walpole (1717-1797) was the owner of a bezoar stone, which he acquired from the estate of his friend, the poet Thomas Gray (1716-1771). The 1784 publication Description of Strawberry Hill, Walpole’s House at Twickenham, included ‘a large Goa stone’ and ‘a silver box almost in the shape of an egg, engraved.’ Almost certainly, the latter was a bezoar stone box.

Bezoars of the type for which bezoar cases were made were naturally occurring stones (largely comprising gallstone matter and hair) found in the digestive systems of certain animals, particularly sheep, deer and antelopes. The stones were prized for their supposed neutralising effects on poison. (The word ‘bezoar’ is thought to derive from the Persian ‘pad-zahr‘ (antidote). Artificial bezoars were made by Jesuit priests in Goa and were intended to be used in the same way as natural bezoars: ground bezoar or small chips of the stone were mixed with wine, tea or water as a medicine to counteract ailments such as epilepsy and melancholy, and as an antidote to poison.)

The importance and costliness of bezoar stones meant that they were often mounted themselves with gold and silver – often in filigree – or were encased in elaborate filigree boxes such as the example here. One example in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, is of gold set with rubies and emeralds and is believed to have been made in India in the seventeenth century (see Komaroff, 2011, p. 258.)

The king of Cochin sent Portugal’s Manuel I (reigned 1495-1521) a bezoar stone shortly before the Portuguese began trading there (Jordan, 2007, p. 91).

The box here is in very fine condition and is without losses or repairs. Its smooth curves and intricate work afford it a flawless, jewel-like presence.

References

Jordan, A. et al, The Heritage of Rauluchantim, Museu de Sao Roque, 1996.

Komaroff, L.et al, Gifts of the Sultan: The Arts of Giving at the Islamic Courts, LACMA/Yale University Press, 2011.

Levenson. J. (ed), Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th and 17th Centuries, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2007.