This well-carved hei-tiki from the Maori people of New Zealand is much larger than most examples. It has been in the jewellery collection of a family in southern England since the 1960s.

It is of milky nephrite-like greenstone and is of a more rounded form, as opposed to more elongated forms which seem later.

According to Kaeppler (2010, p. 340), this type of milky greenstone was called inanga or whitebait greenstone, because of its similarity to the colour of whitebait fish. Kaeppler comments that inanga greenstone was the most prized of all greenstone by the early Maori.

The head is inclined toward the left shoulder. The form is finely delineated and the details are in high relief, including well-defined elbows. The arms rest on the hips. The feet are joined together and there remains a suggestion of toes but these are largely worn away.

It is pierced at the top of the head to allow it to be suspended. The hole has been made by drilling into the greenstone on both sides so that the holes meet in the middle. The top of the head above the hole has much wear from suspension.

Precise dating is difficult but because hei-tikis almost certainly were heirloom pieces and given the wear on this example and the rounded shape, we have given it a wide but early dating for 1600-1850, following the dating adopted by the Musee du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac.

A related hei-tiki, formerly in the Oldman collection, and of similar size and of milky greenstone is in the Museum of New Zealand.

Hei-tiki pendants (‘tiki’ refers to the image and ‘hei’ means to suspend from the neck) carved in local greenstone (nephrite, known by the Maoris as pounamu) are among the most iconic of Maori arts. Later examples were carved from greenstone adze heads because the adzes had become redundant with the introduction of metal tools.

Hei-tiki pendants were worn by the Maoris for largely decorative reasons. Their origins might lay in ancestor worship or fertility rites, but by the time of white settlement, they were already largely decorative rather than connected to ritual. Possibly their form is based on that of a human foetus, but this is not universally agreed.

The example here is in excellent condition. There is plenty of wear from traditional use, and perhaps some later, minor wear from having been handled in England over the last fifty or more years.

There are remnants of red around the eyes which might have been highlighted with red sealing wax at one point.

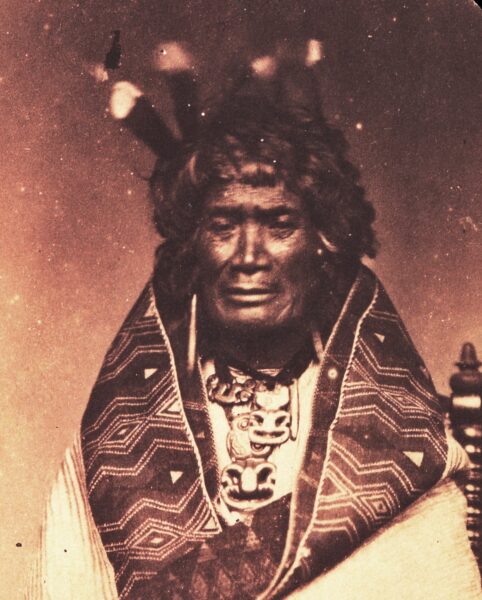

This early photograph dates to around 1860 and shows the wearer with several large hei-tikis worn from the neck.

Scroll down for more images.

References

Austin, D., La Pierre Sacree des Maori, Musee du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac, 2017.

Dodd, E., The Ring of Fire: Polynesian Art, Dodd Mead & Co, 1967.

Kaeppler, A. L., Polynesia: The Mark and Carolyn Blackburn Collection of Polynesian Art, University of Hawaii Press, 2010.

Linton, R. & P. S. Wingert, Arts of the South Seas, The Museum of Modern Art, 1972.

Meyer, A. J. P., Oceanic Art, Könemann, 1995.

Starzecka, D. C., R. Neich & M. Pendergrast, The Maori Collections of the British Museum, British Museum Press, 2010.