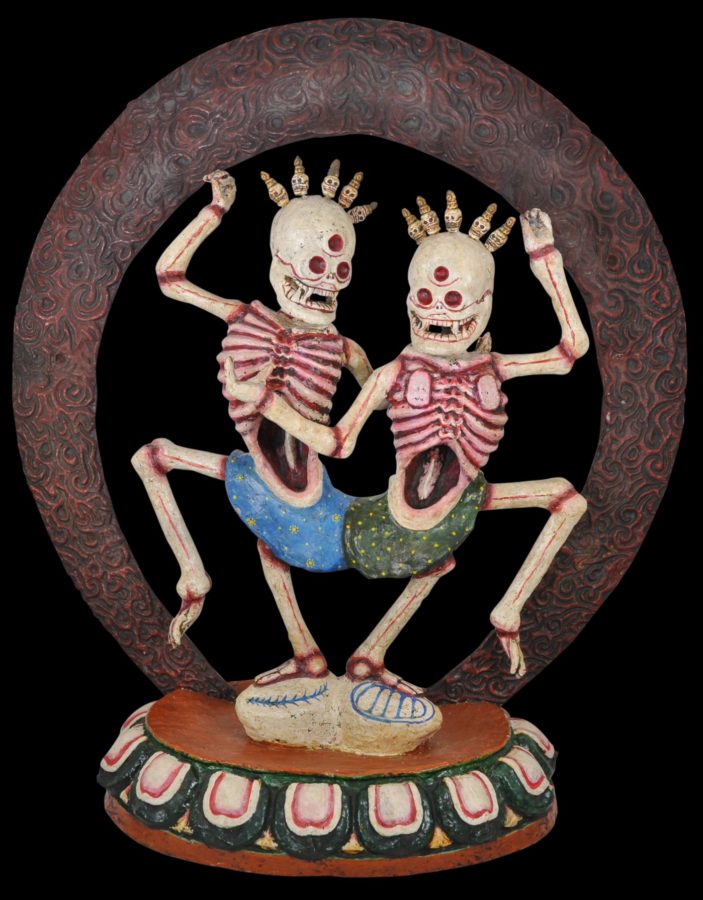

This superb pair of dancing citipati is from 19th century Mongolia. They are shown on a lotus petal base and with an oval backing plate or aureole. The group is made from painted papier mache, wood, clay and cloth. Each balances on one leg only with their arms thrown up in joyous abandon. Each has three eyes (or at least empty eye sockets), and a crown of five mini-skulls, attesting to their high status among the denizens of the underworld.

Their rib cages are particularly evocative with the gaps between the ribs being coloured blood-pink. They wear a green and a blue waist sash.

It is rare to find citipati from the 19th century represented in this way. More typically they are found portrayed on tsa tsa tablets or in tankas or other forms of painting. By the same token, the use of papier mache for sculptural works and masks was common in 19th century Mongolia, almost alone among the Buddhistic kingdoms of the Himalayas and the surrounds.

The citipati are the lords of the funeral pyre and charnel or burial grounds, and are the skeleton companions of Yama, the Lord of Death. And yet, they are intended to be humorous or comic figures in Mongolian and Tibetan sacred dance, despite their gruesome appearance. This accounts for their dynamic dance poses and their smiling countenances.

Citipati are most properly represented as a pair – one is male and the other is female, and most usually (though not always) they are thought to be brother and sister.

The group has not been repainted in anyway. The backing plate or aureole does seen to have had some minor breaks in the past which might have been rejoined but this might be expected given the material from which it is made. These are, nonetheless, relatively difficult to detect, particularly as viewed from the front.

The aureole can be removed from the base.

The base consecration is intact.

Overall, this is a large, rare and highly sculptural item.

References

Berger, P., & T. Tse Bartholomew, Mongolia: The Legacy of Chinggis Khan, Thames & Hudson, 1995.

Meinert, C. (ed.), Buddha in the Yurt: Buddhist Art from Mongolia, Vol. 2, Hirmer, 2011.