Enquiry about object: 9858

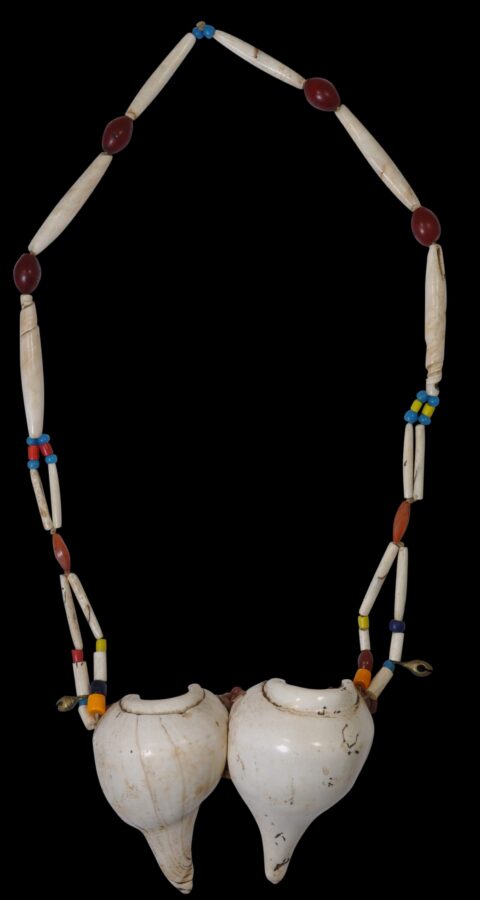

Large Naga Chank Shell & Trade Bead Necklace

Angami Naga People, North-Eastern India late 19th-early 20th century

length of strand: 111cm, length of chank shells: 15.5 and 16cm, weight: 1,251g

Provenance

Hansjorg Mayer Collection, UK

This striking necklace would have been reserved for important festival occasions. Necklaces such as this example, composed of what were rare, expensive and imported items, were prestige pieces worn by the well-to-do to emphasise their status and wealth. Typically, the more elaborate pieces were worn by Naga men – the warriors (kivimi). The right to wear the more elaborate pieces was earned and so the possession of such pieces was linked to status, hierarchy and achievement: the right to wear such ornamentation would be the aspiration of every young person in the tribe, and meant that social mobility could be earned. Jewellery items, like much else, were considered to have a spirit.

It comprises a large pair of chank shell halves; long, cigar-shaped chank shell bicone beads; yellow, blue and red glass trade beads; and four larger, ellipsoid beads carved and polished from red-orange carnelian or agate, with probably origins in Gujarat.

What is not shown in examples published in books, is the reverse of these necklaces and how they are constructed. The example here has a thick bamboo sliver on the reverse. It serves as a crossbar to keep the shell component together and resting evenly on the body. The bamboo components are secured very tightly with ample twisted textile strips.

Such necklaces with large chank shell segments are typical of the Angami Naga of southern Nagaland. They were worn with the chank shell component not resting on the chest but down the wearer’s back, with only the beaded strand visible from the front. In this way, the half chank shells served as a counterweight for the rest of the necklace, as well as being decorative.

The large shell components of these necklaces usually are erroneously referred to as conch shells but they are in fact chank shells (Turbinella pyrum) sourced from the Indian Ocean and most probably in the case here, the Bay of Bengal. The shell is the same as that used in Buddhism and Hinduism and is referred to in this case as the sacred conch or shanka.

According to Untracht (1997, p. 65), the Nagas ‘showed great discrimination when purchasing beads. They never bought irregular or low-quality beads and were fully prepared to pay the high price dealers demanded for beads of superior quality. Dealers knew this and sent only the best quality beads to Nagaland…’

The Naga people are concentrated in Eastern India. Smaller numbers are also in western Burma. The Naga themselves are divided into at least 15 major ethnic subgroups: the Angami, Ao, Chakhesang, Chang, Khiamniungan, Konyak, Lotha, Phom, Pochury, Rengma, Sangtam, Sümi, Tikhir, Yimkhiung, and the Zeme-Liangmai (Zeliang). They speak as many as 30 sometimes mutually unintelligible dialects. Traditionally, they were animists. Each group had their own ceremonial attire.

The area in India where the Nagas, who are believed to be of Mongolian descent, are concentrated was recognised as its own state, Nagaland, in 1977. It is a relatively remote, mountainous and landlocked region, but it was not remote from trade. The Nagas largely were farmers but general trade also was another economic activity, one in which both women and men participated. Costume and ornament making were a significant commercial activity. Some Naga tribes made no ornaments at all but instead bought them from other tribes.

The Naga appreciated imported glass beads and seashell components greatly for their jewellery and other adornment. Typically, the seashells were traded in from the Bay of Bengal. The beads came from India, and also much further afield such as Venice. Metal elements were also used. These were cast locally or imported, mostly from India. The Nagas traditionally were head hunters, and the jewellery of the menfolk reflected the preoccupation with ancestor worship and one’s prowess at hunting and taking heads.

Jewellery items were highly prized and were treated as heirlooms to be passed from family member to family member. Components of necklaces such as individual beads were prized just as much as overall jewellery pieces, and so often beads and other jewellery components would be used and re-used. Jewellery items would be amended and remade according to need and as a family’s wealth and prestige grew. But by the 1970s, the Nagas no longer wore much traditional jewellery and jewellery making for traditional purposes largely stopped. Most Nagas had also converted to Christianity (Baptist mostly), and the taking of heads had long stopped, having been largely supressed by the British in the early 20th century. As with any evolving society, heirloom pieces were traded for items that improved a family’s well-being – medicines, household appliances and so on.

The necklace here is from the collection of well known artist, printer and art publisher Hansjorg Mayer (b. 1943) who built up a large collection of Naga jewellery over a 50-year period, commencing in the early 1970s. Mayer’s works are to be found in the Tate Britain and other museums in Europe.

Illustrated: This actual item is illustrated in Jacobs, J., The Nagas: Hill Peoples of Northeast India, Thames & Hudson, 1990, page 326.

References

Ao, A. S., Naga Tribal Adornment: Signatures of Status and Self, The Bead Society of Greater Washington, 2003.

Barbier, J.P., Art of Nagaland: The Barbier-Muller Collection Geneva, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984.

Giehmann, M., Naga Treasures: Tribal Adornment from the Nagas – India and Myanmar, 2001.

Jacobs, J., The Nagas: Hill Peoples of Northeast India, Thames & Hudson, 1990.

Saul, J.D., The Naga of Burma: Their Festivals, Customs and Way of Life, Orchid Press, 2005.

Sherr Dubin, L., The Worldwide History of Beads, Thames & Hudson, 2009.

Shilu, A., Naga Tribal Adornment: Signatures of Status and Self, The Bead Museum, Washington, 2003.

Untracht, O., Traditional Jewelry of India, Thames & Hudson, 1997.