This rectangular chest, made in Japan around 1600 specifically for the European market, is an example of what is known as Namban lacquerware. Japanese lacquerware was expensive. It was expensive to make and extraordinarily expensive to ship, given its size and the relatively small size of 16th and 17th century sailing vessels.

Two aspects make this example particularly rare – the use of green skin of of stingrays, known as shagreen (a form of decoration known to the Japanese as samegawa-nuri) and the fact that the name of the past owner is inscribed on the box, as part of the design.

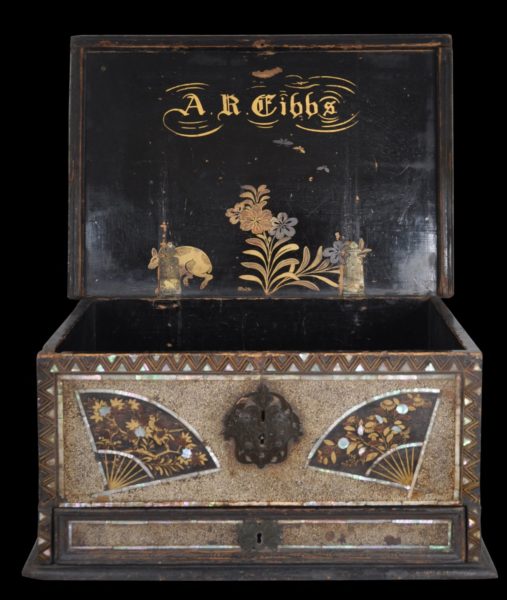

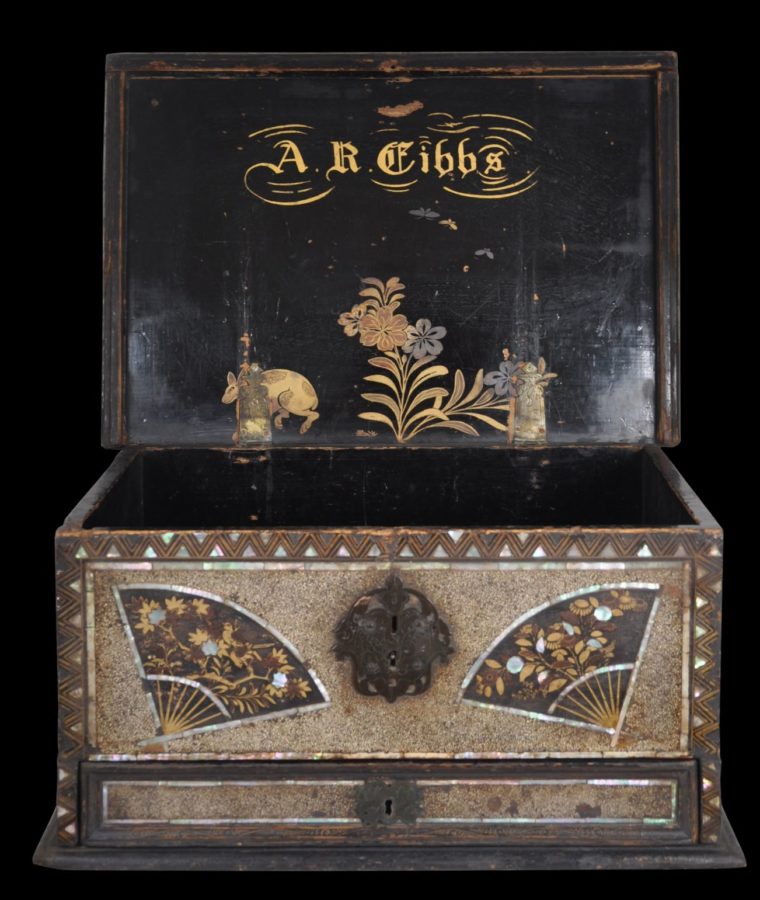

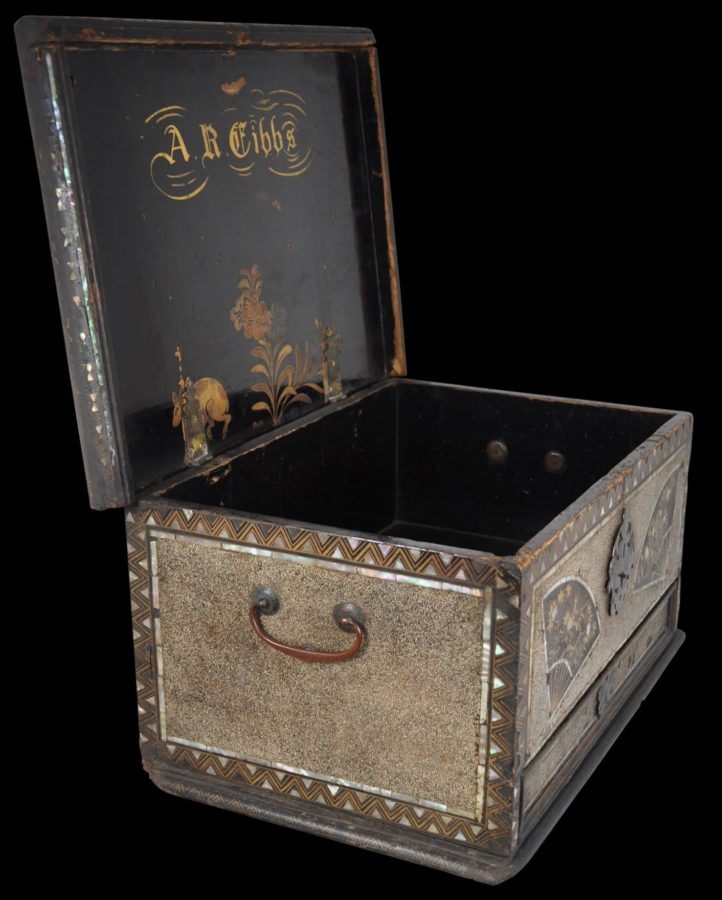

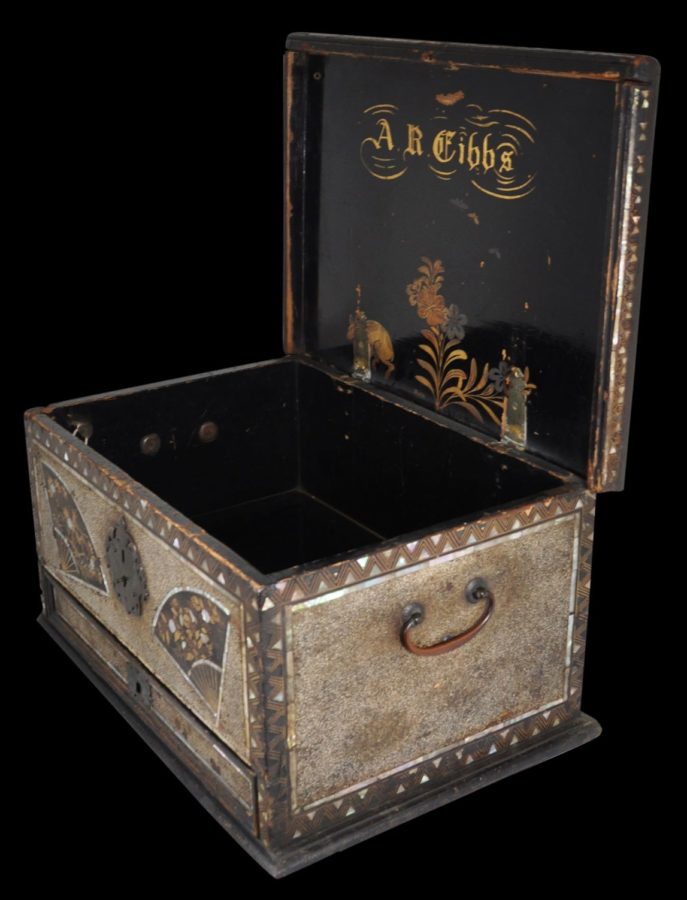

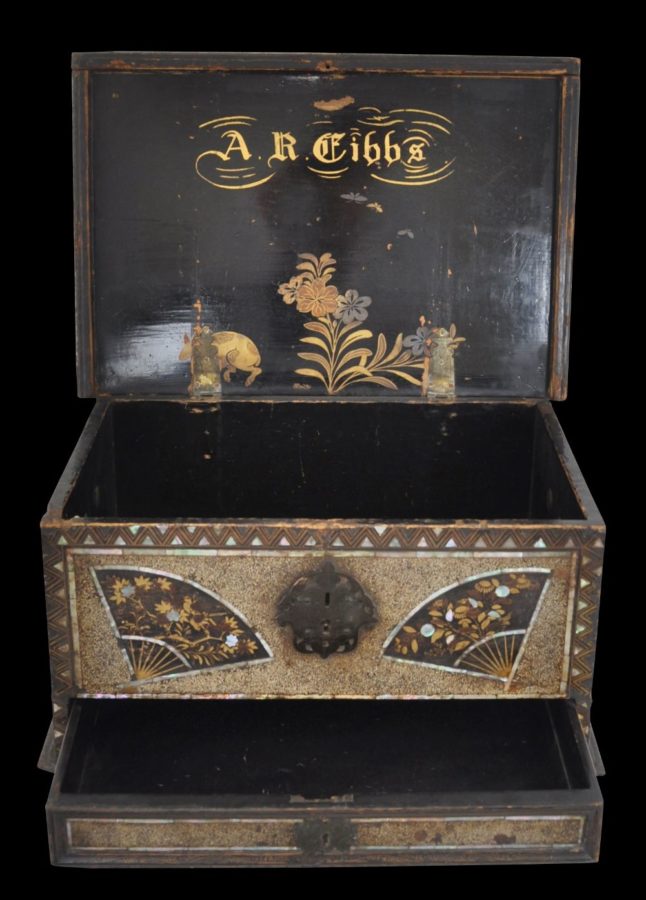

The box has a hinged, overlapping lid on top which lifts to reveal the interior compartment, and a thin drawer at the front, just above the base. A box of similar form and also decorated with shagreen is in the Royal Collection of the British monarch, and is illustrated in Ayers (2016, p. 963).

The top is decorated with one large oriental fan motif, and the front is decorated with two such fans, all against a mottled green shagreen ground. The fans are decorated with sprays of leaves and flowers, and birds. The fan motif is uncommon among Namban wares. One fall-front cabinet attributed to 1580-1620 that is decorated with fans is illustrated in Impey & Jorg, (2005, p. 123) and a domed chest attributed to 1630-50 is illustrated on page 153, for example.

The sides and rear are decorated with large fields of shagreen within leafy borders.

The rounded edges of the lid are decorated in gold with what is known as the ‘Namban scrollwork’ against a black lacquered background (Impey & Jorg, 2005).

The original brass handles are attached on either side and the front of the chest and the small drawer both have large engraved brass key covers or escutcheons which would have been gilded. The lid also retains its original hinges. There is one original round screw cover on the back of the lid; the other now is missing.

The mottled, green skin of of stingrays (shagreen) was obtained in Thailand by the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) and presumably prior to that by the Portuguese and traded to Japan where it was in great demand as a covering for sword sheaths. Occasionally, it was also used in the manufacture of lacquered cabinets, making such cabinets as among the most exclusive items of furniture in their day because so few of them were produced (Veenendaal, 2014, p. 180). An example of s similarly dated, domed chest in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford also is decorated with shagreen.

Both shark and ray skin contain placoid scales which are tiny denticles which help reduce the friction with water. To decorate a chest in shagreen, the skins were first soaked and left to decay. The denticles were then extracted, cleaned and arranged over the surface of the chest before it was lacquered and then polished. The dentciles would often be carefully sorted and arranged according to size (Corrigan et al, 2015, p. 156f).

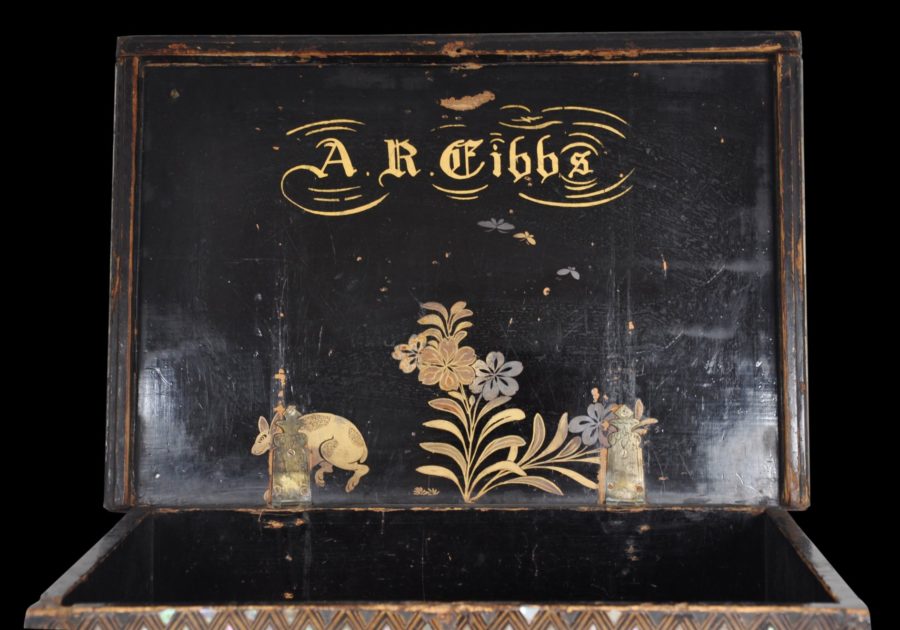

The interior of the lid is annotated in gold lacquer in pseudo-Gothic lettering ‘A.R. Tibbs’. As such, this is one of the few examples of Namban lacquer decorated with the name of the past owner. It is unclear if such names were added at the time of manufacture in Japan or soon after. Impey & Jorg (2005, p. 87) illustrate a chest similarly decorated in gold lettering with past owners’ names. The interior cover here is also decorated with moths, foliage and a mammal-type creature.

Pope Gregory XIII granted Portugal in 1580 exclusive rights to maritime trade east of the Red Sea to as far as seventeen degrees east of the Moluccas (in today’s eastern Indonesia). Japan thus became one of the new sources for exotic luxury goods that could be imported to Europe for profit. Lacquered chests and other objects inlaid with mother-of-pearl were acquired by the Portuguese from Gujarat in India but the superiority of Japanese mother-of-pearl inlaid lacquer was quickly noticed and so Japan became a new source to feed European demand.

The chests and other objects were lacquered in black (urushi), decorated with gold and silver dust (maki-e) and then inlaid with pearl shell (raden). The items became known in Japan as namban, literally ‘southern barbarian’ but perhaps more appropriately translated as ‘exotic’, and was a reference to the Portuguese who commissioned the goods.

The growth in the Portugal-Japan trade was remarkable for it was only in 1542 or 1543 that the first Europeans visited Japan – three Portuguese sailors landed at Tanegashima after the Chinese junk in which they were sailing apparently was blown off course. The Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier arrived in 1549 The Jesuits made big, early inroads and were particularly successful at propagating Christianity in the south. It is likely that the first Namban lacquerwares made for the Portuguese were in fact made for the Jesuits.

The Portuguese were expelled from Japan in 1620 and the Dutch United East India Company or Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) supplanted the Portuguese. After this date and after an initial period when the VOC did not buy Japanese lacquer, the style of lacquerware exported from Japan changed from having obvious Iberian influence to accord more with Dutch and English tastes.

The condition of this cabinet reflects its age. Most extant examples of Namban lacquer have been the subject of substantial restoration if they are in perfect condition. Our example has not be restored and is in its original condition. Accordingly, there are age-related losses to the pearl-shell inlay, to the lacquer and the lower edge at the back, all of which reflect its 400 years or more of age.

References

Ayers, J., Chinese and Japanese Works of Art: IN the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, Vol. III, Royal Collections Trust, 2016.

Bennett, J., & A. Reigle Newland, The Golden Journey: Japanese Art from Australian Collections, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2009.

Cattaneo, A. et al, Portugal and the World: In the 16th and 17th Centuries, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon, 2009.

Christie’s London, ‘Important Jesuit Lacquers and Japanese Works of Art from the Age of Western Influence’, November 19, 1985.

Clode Sousa, F., et al, Obras de Referencia dos Museum da Madeira, Instituto dos Museus e da Conservacao, 2009.

Corrigan, K., J. van Campen, & F. Diercks (eds.), Asian in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age, Peabody Essex Museum/Rijksmuseum, 2015.

Flores, J.M. et al, Os Constructores do Oriente Portugues, Comissao Nacional para as Comemoracoes dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, 1998.

Impey, O., & C. Jorg, Japanese Export Lacquer 1580-1850, Hotei Publishing, 2005.

Museum of Christian Art, Rachol, Goa, 1993.

de Kesel, W., & G. Dhont, Flemish 17th Century Lacquer Cabinets, Stichting Kunstboek, 2012.

Tilley, W.H., ‘Treasures from the Christian century’, Arts of Asia, September-October 1986.

Veenendaal, J., Asian Art and the Dutch Taste, Waanders Uitgevers Zwolle, 2014.

Weston, V. (ed.), Portugal, Jesuits, and Japan: Spiritual Beliefs and Earthly Goods, McMullan Museum of Art, Boston College, 2013.