Enquiry about object: 6762

Pair of Aristocratic Balinese Doors Carved in High Relief with Gilding

Bali, Indonesia late 19th century

length: 184.4cm, width (of the pair): 71cm

Provenance

UK art market

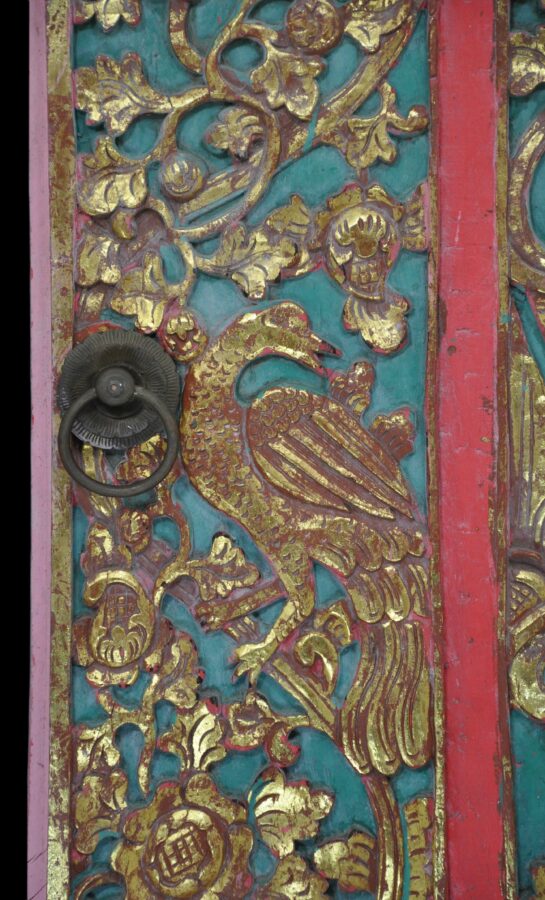

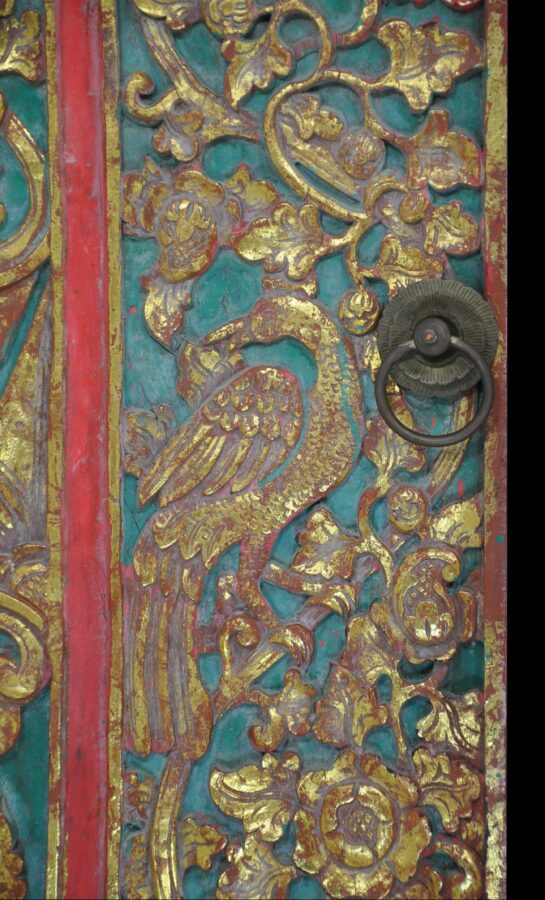

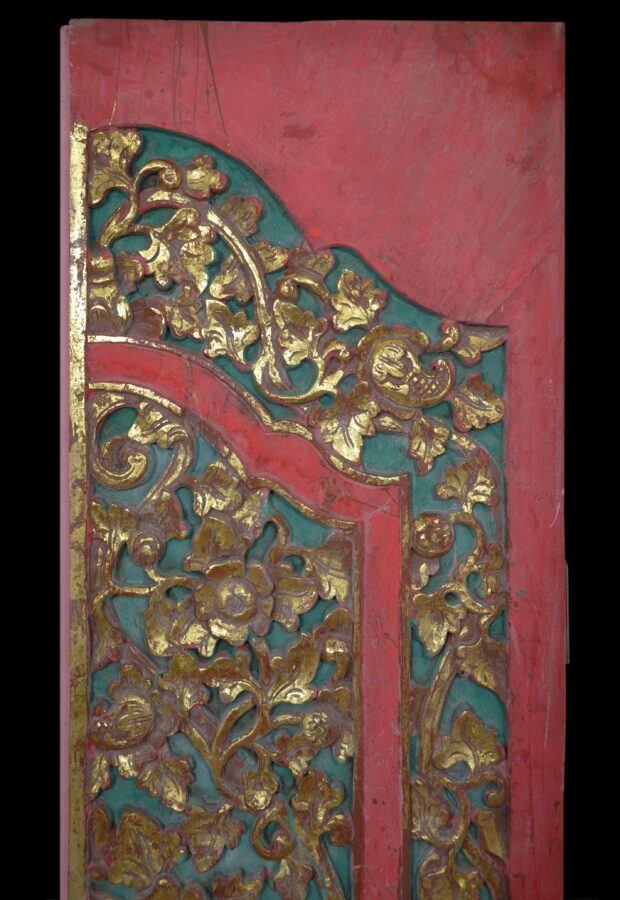

This fine pair of wooden doors from Bali, are carved beautifully and elaborately in high relief. Each door has been fashioned from a single wooden plank. The borders are painted red-pink, the background is in turquoise blue-green, and the raised sections have been highlighted with the ample application of gold leaf. The doors are fitted on the front with their original cast brass ring-pull handles, and on the reverse with English Georgian-era brass knobs.

The central parts of the doors have been carved with resting stork-like birds. The lower registers are carved with a pair of typically Balinese winged lions (singa). The singa probably are protective – their wings are prominent, their mouths are open revealing their sharp teeth. Thy also wear neck ornaments. The rest of the carving comprises scrolling flower motifs known as patera Cina, literally the ‘Chinese flower’.

A set of doors in with a similar colour scheme in the National Gallery of Australia, and attributed to the late 19th century, is illustrated in Maxwell (2014, p. 70).

Elaborately carved doors were used in prominent Balinese pavilions (bale) within the palaces (pura) of Balinese royalty. Possibly it is from one of the places in the vicinity of Singaraja, the capital of Buleleng, a once powerful and prosperous kingdom founded in the 17th century, which once ruled all of north and west Bali. The Dutch conquered the forces of the Raja of Singaraja in 1843.

A northern Balinese provenance for the doors is suggested by the exuberant, Chinese-influenced motifs that might be expected in the more trade-oriented north, where local Chinese dominated commerce in the towns and ports.

According to Reichle (p. 167), gateways are integral to the division of space in Balinese architecture. Almost all Balinese buildings – temples, palaces and household compounds – comprise a series of courtyards separated by wall and by function. Temples, for example, are divided between outer and inner courtyards; between sacred spaces and the more secular. Temples are places where humans, gods and ancestors meet; and on festival days, the Balinese viewpoint is that the traffic of beings, supernatural and otherwise, can be immense. Mrazek (1989, p. 81) illustrates a related set of doors and says that they provided a divide between a raja’s or prince’s quarters and the outside, providing a ‘magically charged threshold between safety and a demonic ‘outside’.’

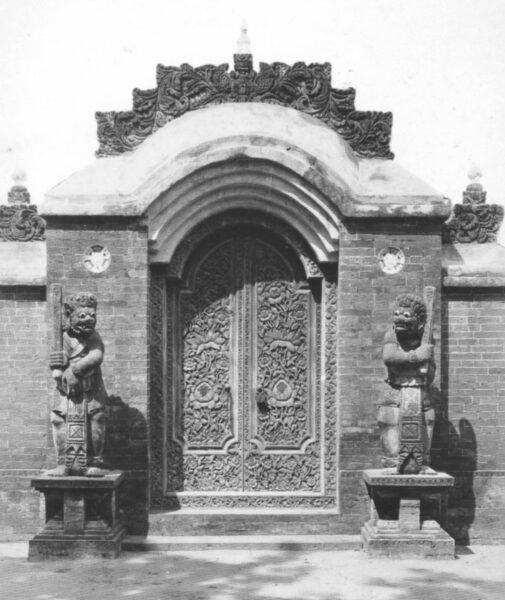

Balinese-style doors carved in high relief also were used in palaces on neighbouring Lombok. The image below, from 1894, shows a palace door that was part of the Mataram-Cakranegara kingdom on Lombok.

It is likely that the doors came to Europe during the age of steamship travel. The emergence of steam travel between Asia and Europe occurred around 1870. Steamships were bigger and faster and had much greater capacity to carry cargo. It is around this time onwards (until the advent of air passenger travel) that passengers suddenly were able to bring large items back to Europe collected on their travels. The opening of the Suez Canal on 1869 further encouraged this trend which allowed travel by steamship to be faster and cheaper.

The doors here are in excellent condition.

References

Baird, C., ‘Captain Thomson’s letter: A discussion on ‘China Trade’ furniture with particular reference to the port of Singapore’, Furniture History, Vol. 45, 2009.

Genscher, H.D., & M. Kusumaatmadja, Java und Bali, Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1980.

Ibbitson Jessup, H., Court Arts of Indonesia, The Asia Society Galleries/Harry N. Abrams, 1990.

Maxwell, R. et al, Bali: Island of the Gods, National Gallery of Australia, 2014.

Mrazek, R., Bali: The Split Gate to Heaven, Golden Press, 1989.

Ramseyer, U., The Art and Culture of Bali, Oxford University Press, 1977.

Reichle, N. (ed.),Bali: Art, Ritual & Performance, Asian Art Museum, 2010.