Enquiry about object: 9194

Rare & Important Early Japanese Calendar Scroll Painting of the Sanju Banjin

Japan, probably Kyoto Muromachi or Momoyama Period, 16th Century

width (without frame): 57.4cm, length: 120.5cm

Provenance

from the collection of an aristocratic Spanish family, purchased from Shreve, Crump & Low of Boston in the late 1970s or early 1980s

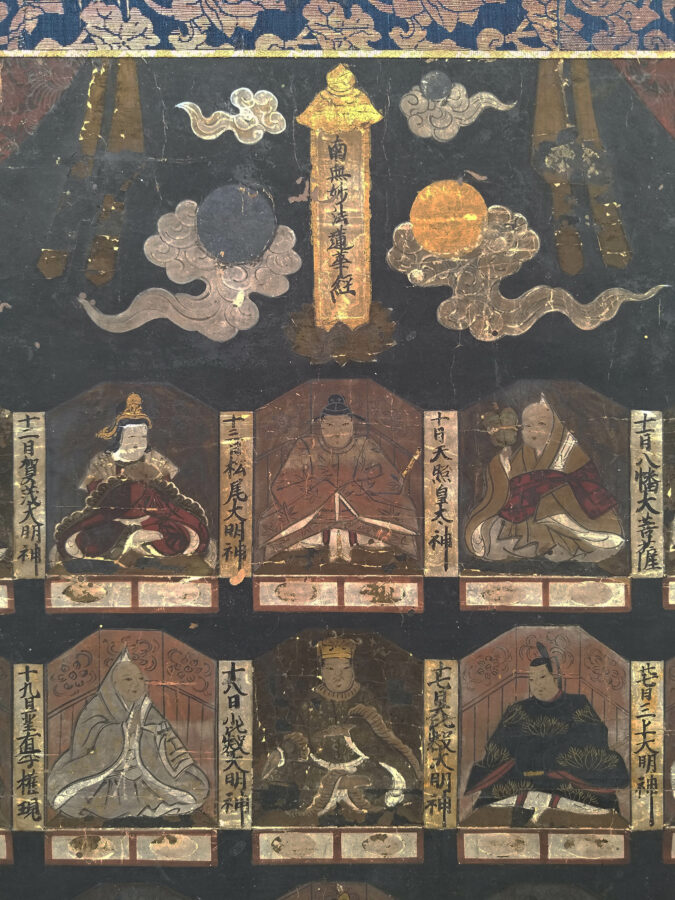

This rare 16th century painting in ink, pigments and gilt on paper, is from Japan, almost certainly Kyoto, and is in the Tosa style of Japanese painting. Shown are portraits of the thirty Shinto (Hokke school) protective or guardian deities or kami (native deities of significant shrines from around Japan). Specifically, these kami are the Sanju Banjin – each represents the thirty days of the month. Each god is shown seated on a dais, and wearing rich garments. Each portrait has an inscription that identifies the day and deity represented, though in Hokke thinking it was not that each kami was individually responsible for a specific day but rather that they were collectively responsible.

The upper part of the painting is decorated with drawn curtains. The sun and moon atop scrolling clouds are between the curtains.

There is an illegible inscription to the right of the curtains. A legible panel between the sun and the moon reads ‘Namu Myoho Renge Kyo’ or ‘Glory to the Dharma of the Lotus Sutra’.

The lower section of the painting shows a pair of Ishin shishi or late Edo-period samurai figures, and two divine archers, plus lion dogs and guards on each side of a flight of stairs.

The lower left corner with a four-character signature which reads ‘Hoin’ or ‘Seal of the Law’ which is the highest rank awarded to Buddhist artists, and possibly ‘Nichihisa’.

The painting is mounted with a Chinese Qing Dynasty brocaded lotus satin with lotus scrolling against a dark blue ground. The frame is of black lacquer.

The Tosa style of painting was founded in the early Muromachi period (14th–15th centuries) and drew inspiration from ancient Japanese art, rather than schools influenced by Chinese art. Tosa school paintings are characterised by areas of flat opaque colour enclosed by simple outlines. The drafting is precise and conventional. Typically, narrative subjects are drawn from Japanese history and literature.

The thirty kami were believed to protect the peace and happiness of the nation during the thirty days of the lunar month. Legend says that the Abbot Ennin (794-864) invited the kami to Mount Hiei to protect a copy of the Lotus Sutra that he had enshrined in the mountain. Such a story no doubt was an attempt to graft Buddhist beliefs onto existing Shino beliefs.

Generally, the names of the thirty Sanju Banjin are Kasuga, Matsuo, Hachiman, Hachiōji, Shōshinshi, Dai Hiei (Ōmono no nushi), Mikami, Sekizan, Sumiyoshi, Hirota, Atsuta, Hirano, Kifune, Kitano, Keta, Amaterasu, Kamo, Ōhara, Nōka, Ko Hiei (Ōyamakuinokami), Marōdo, Inari, Gion, Takebe, Hyōzu, Kibitsu, Suwa, Kehi, Kashima, Ebumi, and Toyo iwamado no kami.

The earliest records of the Sanju Banjin however date from the late 11th century but they became particularly popular in the Muromachi period (1333-1573). Paintings like this one were used during Buddhist rituals of the Tendai Lotus School and the Nichiren sect, two Buddhist sects that incorporated Shinto elements.

Worship of the Sanju Banjin was promoted by the Hokke Shinto school which was prominent in the Kyoto area, Japan’s old imperial capital. Sanju Banjin was at the centre of Hokke Shinto beliefs. The school incorporated the beliefs with Buddhism. However the Meiji Restoration of the second half of the 19th century sought to extract Shintoism from Buddhism and prohibited combinatory cults. Edicts specifically banning Sanju Banjin worship were issued. in 1868 for example. It is likely that during this period many depictions of the Sanju Banjin such as the scroll here were destroyed or damaged.

For what aims were the Sanju Banjin venerated? Petitioners could appeal to them if their action had violated a promise they had made. Requests for protection and release for illness could also be made. It is likely that they were also invoked in exorcism rituals.

Shintoism is the indigenous religion of Japan. It paces much emphasis on myriad deities and spirits often associated with places such as streams, mountains and forests. Buddhism arrived from China, and offered a radically different set of beliefs from those previously held – not least its offer of a concept of salvation rather than the nebulous, unappealing eternity of an underworld. Shinto was very much concerned with reverence for spirits and placating them. Buddhism however, introduced the notion of karma thus bringing the focus back to the individual and how they might lead a meritous life with rewards that they basically could win for themselves. Both religions were accommodated, with adherents mostly following not one strand or the other but a blend of each but in varying degrees.

Most scroll paintings of the Sanju Banjin probably showed them arrayed in mandala form and not necessrily with all thirty. The scroll painting here is very much in portrait form aimed at securing which kami comprise the Sanju Banjin.

There are very few – perhaps as few as six – documented scroll paintings of the Sanju Banjin in non-mandala form. Dolce (2003, p. 224) illustrates an example in Hompo-ji Temple in Kyoto, from the Muromachi period which is attributed to a master of the Tosa school. It is very similar to the example here and is similarly shown with Chinese brocaded silk.

Also, the Chishaku-in Temple, Kyoto, has a comparable scroll painting of the Sanju Banjin which is dated 1580, and Daihoji Temple in Takaoka City, has another similar depiction of the thirty deities, by Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1610) and dated 1566. See also a portable shrine containing small statues of the Sanju Banjin in the British Museum.

The example here is a hanging scroll on paper but has been later mounted (presumably in Japan) on board. There is some rubbing and surface loss to the painting but it is in relatively well-reserved condition given that it dates to the 16th century.

References

Dolce, L., ‘Hokke Shinto: Kami in the Nichiren Tradition,’ in Teeuwen, M., and F. Rambelli, eds., Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm, Curzon/Routledge, 2003.

Kuhn, D., (ed.), Chinese Silks, Yale University Press, 2012.