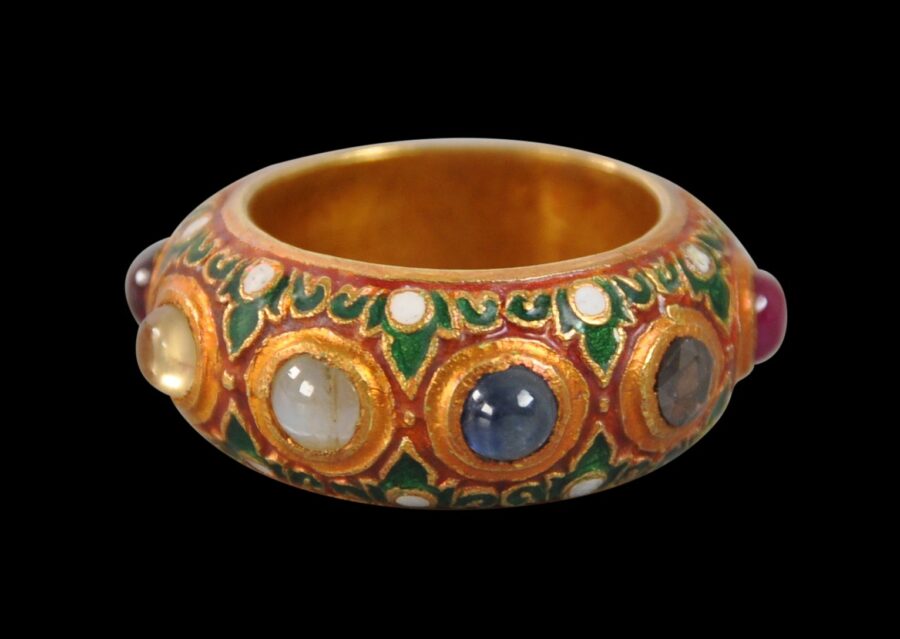

This exquisite gold ring originally from a minor palace in Bangkok and designed for a member of the extended Thai royal family, has been decorated with green, white and red enamel, and set with the nine planetary gems.

The enamelwork, which is especially intricate and intact, has been arrayed as small leafy motifs.

The nine gems are evenly spaced. The number nine is considered the most fortuitous number in Thailand – when said in Thai the word for ‘nine’ also sounds like the Thai word for ‘moving forward’ or ‘progress.’

The nine gems typically are moonstone to represent the moon, diamond (Venus), ruby (Sun), garnet or coral (Mars), emerald (Mercury), topaz or yellow sapphire (Jupiter), blue sapphire (Saturn), garnet (the eclipse of or the ascending moon), and cat’s eye (Comet). The concept of nine planetary gems originated in India where they were used as talismanic devices and called the nava-ratna.

In the case of the ring here, the diamond is a rose-cut black diamond. All the other stones are cabochons.

The kings of Siam participated in elaborate processes of gift exchange with other heads of state around the world as well as with other kings, princes and sultans closer to home. This called for the manufacture of significant quantities of gold and silver luxury goods of which jewellery was a component.

Accordingly, a nine-gem gold ring of similar form was part of the diplomatic gifts presented in 1861 to Napoleon III at Fontainbleau by the ambassadors of King Mongkut of Siam. That ring is illustrated in Bruley (2011, p. 89) and is in the collection of the Chateau de Fontainbleau, near Paris. A similar ring is illustrated in Richter (2000, p. 94), which is described by the author as an ‘outstanding’ example of 19th century Bangkok jewellery.

Also, several 19th century Siamese kings were especially polygamous (King Mongkut [Rama IV] and 43 consorts and King Chulalongkorn [Rama V] had 153) and this lead to a proliferation of royals in 19th century Bangkok. As a consequence, many secondary palaces were established and each minor royal household required its own princely regalia and possessions. All this meant that Bangkok became home to particularly skilled gold and silversmiths given all this significant demand.

Today in Thailand, the overall number of Thai royals is contracting. The Thais followed the Chinese system of nobility whereby the descendants of a king were awarded royal titles, but these fell by a rank with each generation so that eventually, most descendants will become commoners. With this goes the loss of privilege and the dilution of wealth. As a result, items such as this ring become available on the open market. The availability of such items was helped in the 1930s and 1940s when the Thai monarchy relocated to Switzerland. Other family members also left Siam/Thailand and settled in Europe and as a consequence, princely Thai items occasionally can be found in Europe.

The ring here is wearable, stable, and historically important. There are no losses to the enamel work. It is in excellent condition.

Above: Jean-Léon Gérôme, ‘Reception of the Siamese ambassadors by the Emperor Napoleon III at the Palace of Fontainebleau, June 27, 1861′ ( Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

Scroll down for more images.

References

Bruley, Y., et al, Le Siam a Fontainbleau l’Ambassade du 27 Juin 1861, Chateau de Fontainbleau, 2011.

Richter, A., The Jewelry of Southeast Asia, Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Salmon, X., et al, Chateau de Fontainebleau: Le Musee Chinois de l’Imperatrice Eugenie, Chateau de Fontainebleau, 2011.