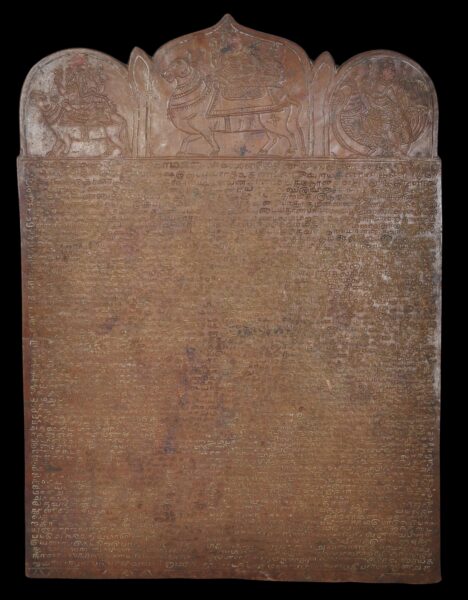

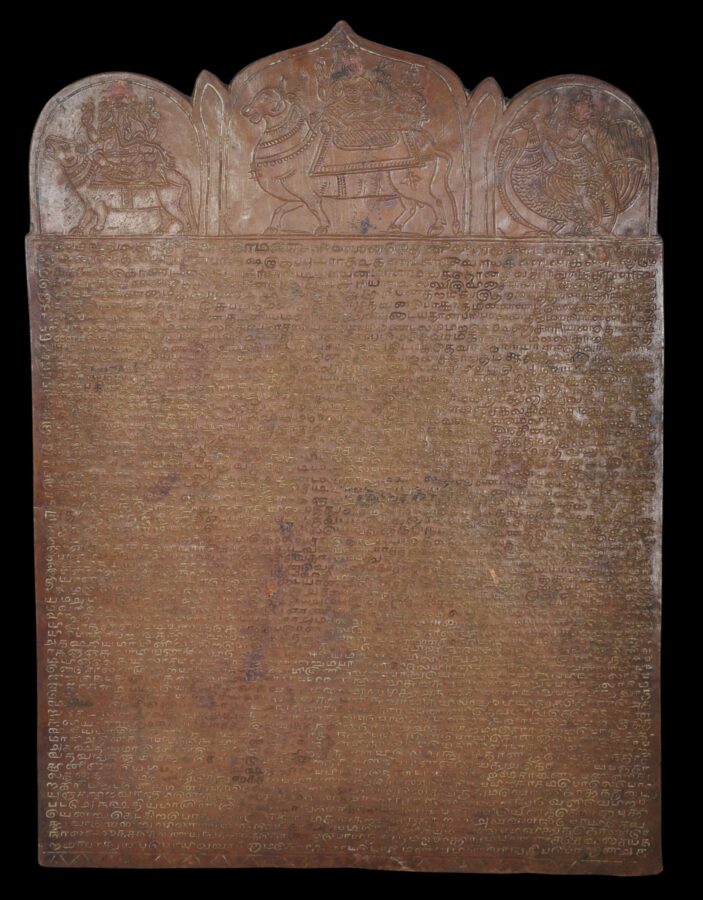

This double-sided inscribed legal grant or hakku patra, probably giving the holder the right to use land, is a rectangular, arched metal plaque. On one side, the plaque is engraved with figures at the top of Shiva and Parvati on their vahana, Nandi, and flanked by figures of their sons, Ganesha on his rat, and Subrahmanya on his peacock. Beneath is 63 lines of Tamil script.

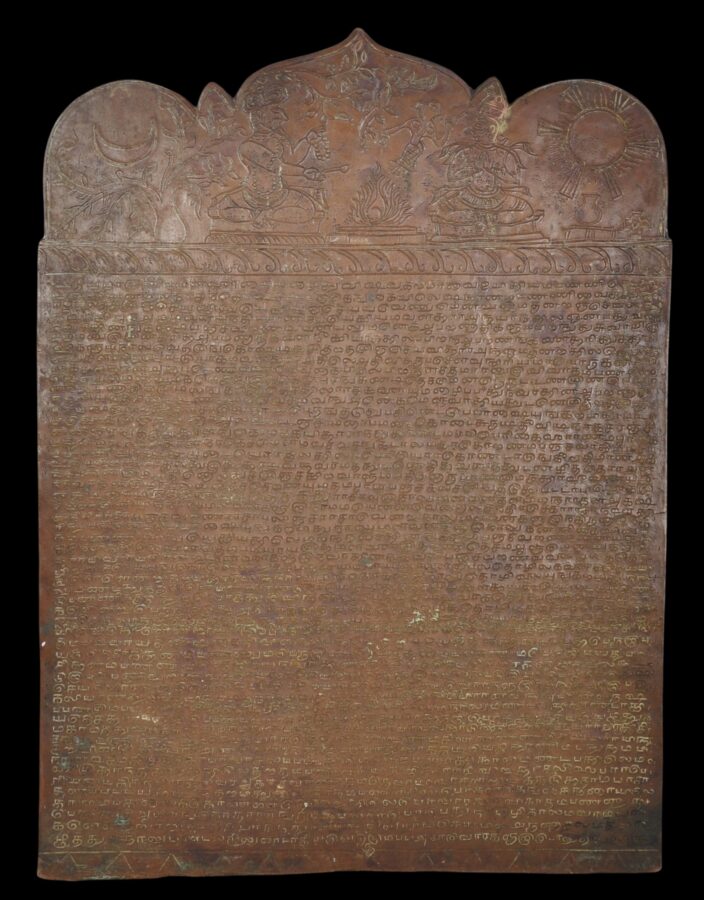

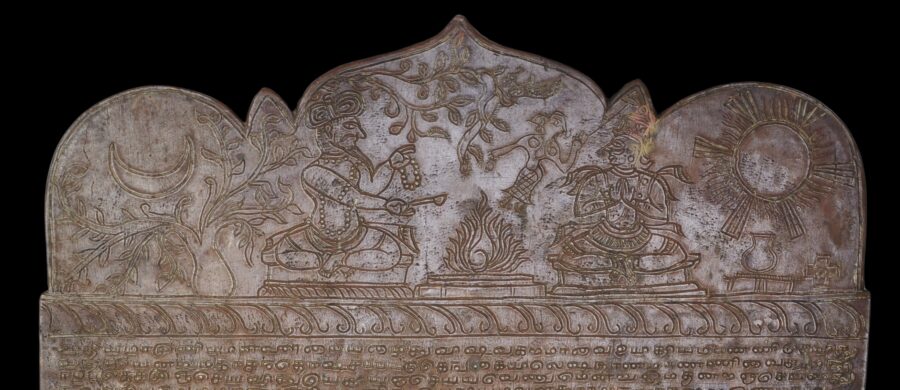

The other side is engraved with a devotional scene with a priest and devotee, flanked by the sun and moon, and another 54 lines of Tamil script.

What is a hakku patra?

In India’s south, hakku patras were a legal grant or an entitlement for certain privileges, bestowed or endorsed by some authority, usually a local ruler, to an individual, group of persons, or caste or sub-caste, to own or use land, or to have some sort of exclusivity over the provision of services, usually occupational, such as the privileges that might be accorded to a guild.

The bestowal of such right has been common in India since ancient times. Extensive revenue and land grants were given to Brahmins but similar and other rights were given to almost every level of society. Artisans were give rights to operate in their field (to the exclusion of others) and even itinerant folk performers who might travel from village to village were granted such rights for specific geographic areas. Such a grant protected the holder from competition and allowed them to earn more income than they otherwise would.

Hakku patras sometimes were inscribed on paper but more usually were engraved on metal sheets (in which case they were in ragi rekula form) to emphasise their importance but also because the grants usually flowed from one generation to the next and so the enabling documentation needed to be in a permanent form. The importance of a hakku patra meant that such documents were kept safely and securely. Often their whereabouts was a secret known only by a trusted few.

Typically, a hakku patra did not just bestow a grant but also set out the recipient individual or community’s genealogy and historical rationale (apocryphal or not) as a means of demonstrating why the grant was warranted. Often the inscriptions end with a curse on those who might seek to tamper with the gift or grant in future.

The hakka patra here comes with a custom-made wooden and perspex stand.

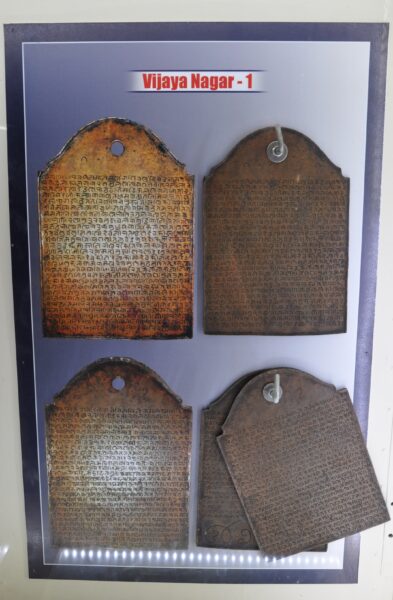

Above: Similar hakku patra land grants displayed in the Government Museum, Chennai, South India.

References

Goswamy, B.N., The Word is Sacred, Sacred is the Word: The Indian Manuscript Tradition, Niyogi Books, 2006.

Rao, T., ‘Study and collection of Hakku Patras and other documents among folk communities in Andhra Pradesh’, Endangered Archives Program, British Library, 2009.