Enquiry about object: 9432

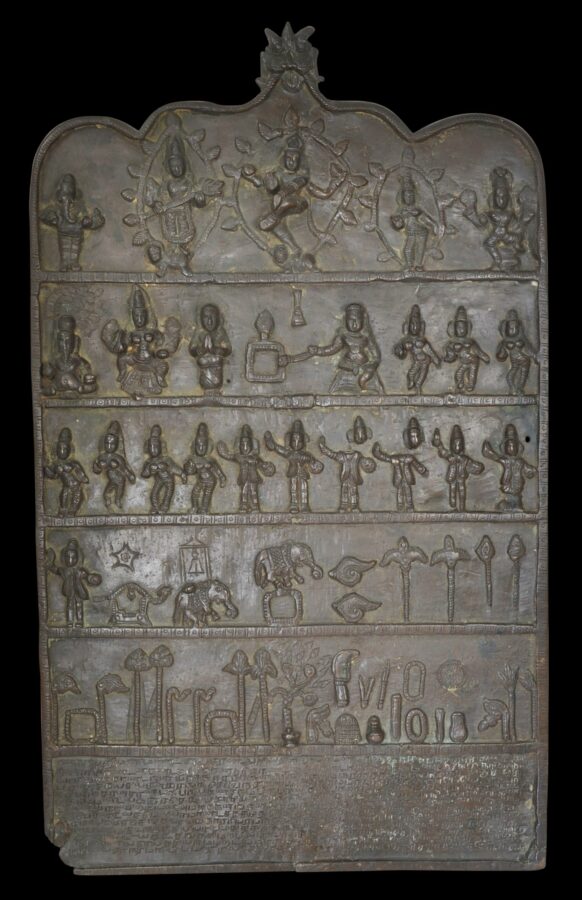

South Indian Bronze, Double-Sided, Charter Plaque (Pattayam) with Lengthy Tamil Inscriptions

South India 18th-19th century (dated 13th-early 14th century)

height: 40.5cm, width: 24.5cm, weight: 3,562g

Provenance

private collection, UK; acquired at Spink, London, April1980.

This South Indian plaque is based on a legal grant or hakka patra used widely in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka but is more of a charter or pattayam.

It is of cast and engraved bronze and is unusually large and heavy. It is also unusual because it was made in the colonial era – 18th or 19th century – but carries a date in the late 13th or early 14th century, either 1205 or 1251 in the Tamil calendar (an addition of 78 years gives it a Gregorian calendar year).

The colonial era dating is confirmed by the use of colloquial Tamil and its mention of Ceṉṉā paṭṭaṇam (line 72) – a name for the port city of Madras (Chennai) peculiar to the colonial rather than earlier periods.

The plaque is of rectangular form with a crenulated arch at the top surmounted at the front by a protective kīrtimukha mask. The kīrtimukha’s placement at the peak of the curved arch is no coincidence. It acts as an overarching prabhavali or circle of flames or aura for the narrative panel associated with the deity Siva, as seen at the Swetharanyeswarar Temple (Tiruveṇkāṭu Svētāraṇyēsvarar Tirukkōvil) in Tamil Nadu.

There are six tiers or registers beneath the kīrtimukha.

The first and main register is dedicated to the principal deities of the Swetharanyeswarar Temple – so, from left to right, cast in high relief stands Vinayaka, the elephant-headed son of Shiva; Aghoramūrti, a fierce incarnation of Shiva (identifiable by the trident held sloping upwards right to left, also Aghora one of the five heads of Shiva and this is indicative of the southern direction); Shiva as Naṭarāja, the Lord of Dance (included here because the Swetharanyeswarar Temple is also known as Āti (or Adi meaning that which came first) Chidambaram as legend has it that Shiva danced here before he did at Chidambaram where the Thillai Nataraja Temple now stands); Periyaṉāyaki (the main goddess at the temple is called Vityāmpāḷ); and an unidentified male deity of lesser importance perhaps Subrahmanya (suggested by the lack of aura) on the far right.

Lines 89 – 91 of the inscription support the association with the Swetharanyeswarar Temple. They read:

Transliteration:

- … … … … … … … … … … Akōṟamūṟtti cuvēta-

- raṇṇiya periyaṉāyaki cuppiramaṇiyar piḷḷaiyār caṇṭikēcurar yivarkaḷai

- cēviccāleṉṉa palaṉō appalaṉai peṟṟu cukattil vāḻakaṭavarākavum

Translation:

[those] who worship Agoramurti, Svetaranniya Periyanayaki, Subrahmanyar, Pillayar, Candikeswarar, shall benefit from the fruit of such worship and live a life of contentment.

The second register has what might be warriors, as does the third register, two of whom are separated from their heads. The self-decapitating figures seem to suggest worship of the goddess Kali, a goddess who also happens to be one of the principal deities at the Swetharanyeswarar Temple.

The fourth register shows a deity or warrior, elephants (used in battle), two conches (used in rituals but also battle calls), and weapons.

The fifth register shows more weapons such as the axe, naga astra, spears and so on. This is all suggestive of the practice of Kali puja (line 74 of the inscription makes mention of this ritual) or Kali worship in preparation of war.

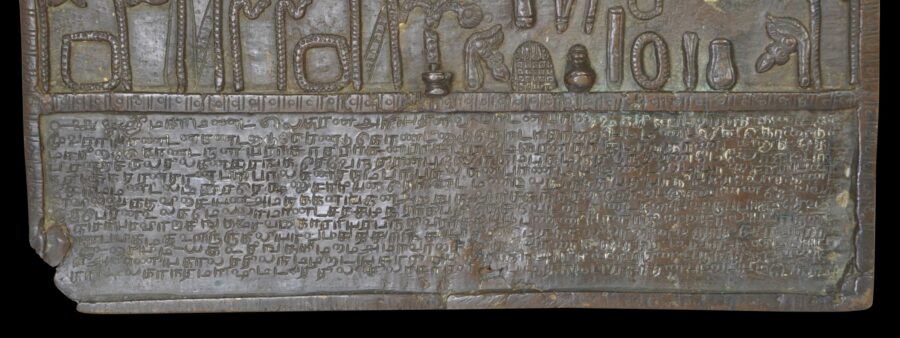

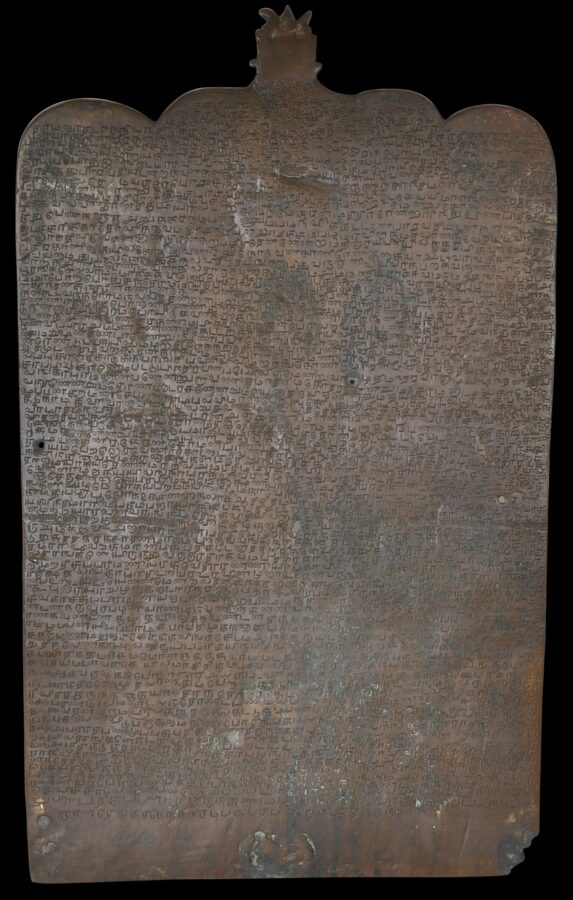

The final register is engraved with 13 lines of Tamil. The reverse is similarly inscribed with dozens of lines.

The Tamil used is at times rudimentary and difficult to translate because of the tendency to run words and sentences together. The text is rambling, copies texts from historical inscriptions but combines it with insertions written in colloquial language. It commands the reader to honour this pattayam or charter.

The author uses threatening phrases loosely translating as ‘I promise you that you will be in trouble’ (line 87) directed at those who might disrespect or dishonour the charter or the religious leader it mentions who belongs to the pasupata order.

The inscription provides the names of certain individuals who appear to have rights to perform rituals at the temple or associations associated with the monastic order. Given that the right to perform rituals often came with the right to own or use tracts of land, it is possible that the plaque was produced to substantiate any such land claims perhaps for the consideration of the colonial government. If land claims and other such property rights could be substantiated then the likelihood that the colonial powers would confiscate such lands was lessened. Alternatively, the plaque could have been produced by the monastic order to establish its legitimacy. Another possibility is that it was produced during the Poligar Wars, also known as the Palaiyakkarar Wars (1799-1805), when local feudal chiefs fought against the British East India Company and again, in the area, local land holders were looking to have proof of entitelment to their land.

Some of the names that appear are:

Line 68 – Balumuruga

Line 69 – Sivakasi Subramania

Maruthanadar Tiruchirappalli

Line 70 – Karupura Palaniandikauntan

Kanyakumari Angamuthukauntan

Line 71 – Koundan Kulitthalai

Koundan Thiruthsingode

Kumaraswamy Muppan (forefather of) Salem

Muppan (forefather of) Sabapti Moo

Kanchipuram Samikirama

A related example is in the National Museum, Delhi, and illustrated in Goswamy (2016, p. 83).

The example here is in fine condition, though there is an old loss to one of the lower corners.

What is a hakku patra?

In India’s south, hakku patras were a legal grant or an entitlement for certain privileges, bestowed or endorsed by some authority, usually a local ruler, to an individual, group of persons, or caste or sub-caste, to own or use land, or to have some sort of exclusivity over the provision of services, usually occupational, such as the privileges that might be accorded to a guild.

The bestowal of such right has been common in India since ancient times. Extensive revenue and land grants were given to Brahmins but similar and other rights were given to almost every level of society. Artisans were give rights to operate in their field (to the exclusion of others) and even itinerant folk performers who might travel from village to village were granted such rights for specific geographic areas. Such a grant protected the holder from competition and allowed them to earn more income than they otherwise would.

Hakku patras sometimes were inscribed on paper but more usually were engraved on metal sheets (in which case they were in ragi rekula form) to emphasise their importance but also because the grants usually flowed from one generation to the next and so the enabling documentation needed to be in a permanent form. The importance of a hakku patra meant that such documents were kept safely and securely. Often their whereabouts was a secret known only by a trusted few.

Typically, a hakku patra did not just bestow a grant but also set out the recipient individual or community’s genealogy and historical rationale (apocryphal or not) as a means of demonstrating why the grant was warranted.

However, whilst the plaque here ostensibly is in the form of a hakku patra it more seeks to claim or exert a right rather than is evidence of a right having been granted. To that end, it seems to borrow from other known metal grants. The opening few lines are very similar to செப்பேடு or copperplate grants now in the collection of the Tamil Nadu State archives but originally from the Sivagangai Samasthana Devasthanam and which relate to the land holdings (secular and sacred) of the royal family in Sivagangai. For instance, the Āṇṭāṉ kōyil ceppēṭu(ஆண்டான் கோயில் செப்பேடு), a copperplate grant recording the donation of the town Meenapur in Sivaganga to the Andan temple in Chola country by Vijaya Raghunatha Periya Odiyath Devar in 1799AD, seems to be a possible source for some of the replicated lines.

The pattayam plaque here is in fine condition other than the obvious loss to the bottom left-hand corner.

(Thank you to Nalina Gopal, formerly of Singapore’s Indian Heritage Centre, for her valuable assistance in translating and interpreting this plaque.)

References

Gopal, N., London, pers. comm, 2024.

Goswamy, B.N., The Word is Sacred, Sacred is the Word: The Indian Manuscript Tradition, Niyogi Books, 2006.

Rao, T., ‘Study and collection of Hakku Patras and other documents among folk communities in Andhra Pradesh’, Endangered Archives Program, British Library, 2009.