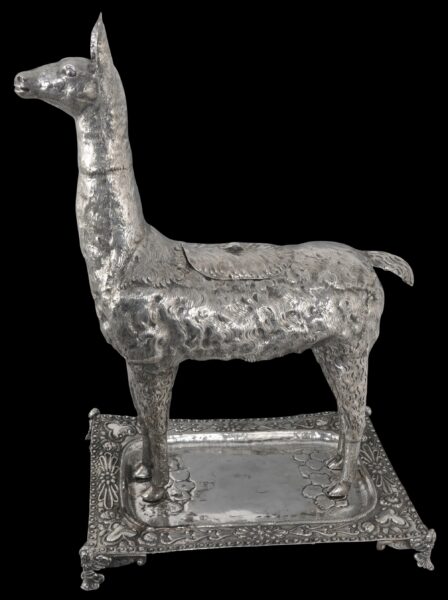

This unusually large and very-well modelled, high-grade silver incense burner or sahumador has been modelled as a llama, rising from a rectangular plate which stands on four feet, each shaped as a winged seraphim. It is from late 18th-19th century Viceroyalty of Peru.

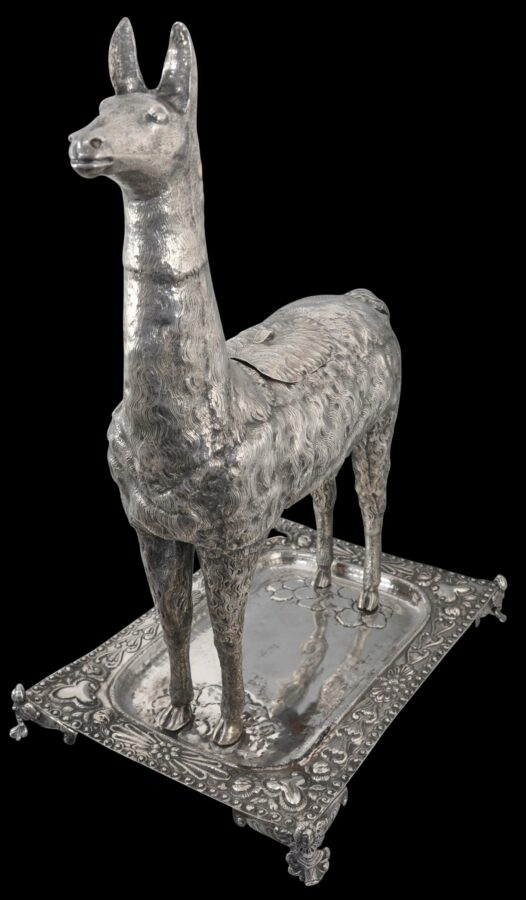

A lid with a small pull is on the llama’s back. Inside, attached to this is a basket into which perfumed embers were placed, and the the lid and basket were placed back inside the body of the llama but at right angles, to allow the smoke to escape, and oxygen in.

The rendering of the llama is life-like and the detail is exceptional. The refinement of the piece suggests it was commissioned for a particularly wealthy client.

The llama has been constructed from several pieces of sheet silver that have been carefully soldered together. It has then been secured to the plate on which it stands by means of bolts with hand-cut nuts, these being apparent on the underside of the tray.

The tray on which the llama stands is repoussed with floral and other flourishes of the late Baroque or Rococo. Such work is typical of European-influenced silverwork of the Viceroyalty of Peru. See Luis Ribera & Schenone (1981, p. 231) for examples of similar, rectangular trays attributed to the 18th century.

Incense burners in 18th century Latin America often were based on animal forms such as turkeys, peacocks and llamas. They were embellished with rococo plant and shell motifs. Related objects made by local silversmiths included hand warmers and portable braziers.

Llamas themselves had inspired Inca silversmiths from as early as the 15th-16th century. LLamas are highland animals and so are associated with the mountains, which were believed to be the abode of the gods, and so themselves were considered sacred. This did not stop them from being used for various practical purposes however. They have been domesticated in the Andes for thousands of years and were also an important source of meat, fibre, and also were used as pack animals. They were also used by the Incas as sacrifice animals.

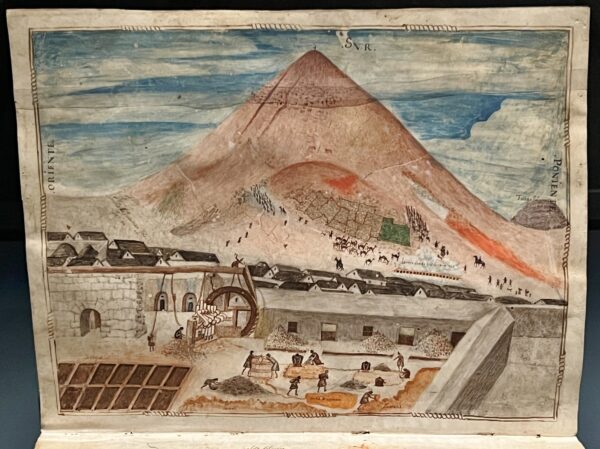

The Viceroyalty of Peru was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542. Originally it contained what today is Peru and most of Spain’s other colonial holdings in South America. Lima was the Viceroyalty of Peru’s capital. Stately homes were built in Lima by the local Spanish aristocracy and their splendid interiors were decorated with grand items of Spanish-influenced furniture. This helped to make Lima the most Spanish city in all of South America. Buildings, both secular and ecclesiastic, were based on 17th century European classicism. Silver mined from the Potosi mines – among the most important silver mines the world has seen – funded much of this and was used locally too by local silversmiths. The shipping port of Seville connected Spain to Viceroyalty of Peru and to Manila and Mexico. The trade was known as the Galleon Trade which saw the distribution of luxury goods across the world. The flow was not one way, but complex and multi-dimensional. The Viceroyalty of Peru lasted until 1824, although over its history it went through various territorial changes.

Above: The silver mines of Potosi, illustrated in a watercolour dating to around 1585. (Photographed at the Royal Academy, London; collection of the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York.)

Baroque is a style that emerged from Rome in the early 17th century. It was a reaction to Luther’s Protestantism and the attendant austerity and so was a celebration of the supernatural with its rich, scenographic ostentation, which spread from Rome to the rest of the Roman Catholic world, including the Spanish-American colonies. Included in this was the double-headed eagle with its imperial connotations, a motif which also became incorporated into the coat of arms of Lima. Baroque remained in vogue for two hundred years and for the rest of the existence of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Other motifs included cornucopias, urns and vases of flowers, rosettes and fruits and vines.

The artistic influence between Spain and Spanish America was not one way. Many of the silver items made in the Viceroyalty of Peru were exported to Spain and so it is likely that the local version of Baroque then influenced Spanish Baroque. The preference in Spain for altars, tabernacles and other items to be clad entirely in silver is something else that might also have been imported from colonial South America.

Similarly, colonial style incense burners were imported into Spain and their use spread from the 18th century.

The llama here is in excellent condition. The silver has a smoothness associated with age and also purity. It is a magnificent example.

References

King, H., Rain of the Moon: Silver in Ancient Peru, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2000.

Luis Ribera, A., & H.H. Schenone, Plateria Sudamericana de los Siglos XVII-XX, Hirmer Verlag Muchen, 1981.

Rishel, J.J. & S. Stratton-Pruitt, The Arts in Latin America 1492-1820, Yale University Press, 2006.

Silverworks from Rio de la Plata, Argentina, Smithsonian Institution, date unknown.

Taullard, A., Plateria Sudemericana, Ediciones Espeula de Plata, 2004.

Torres della Pina, J., & V. Mujica Diez Canseco (eds.), Peruvian Silver and Silversmiths, Patronato Plata del Peru, 1997.