This large, impressive chest with a rounded, half barrel-like, hinged cover, is clad entirely in thick, high-grade silver sheet that has been repoussed in high relief. It is from the Spanish colonial Viceroyalty of Peru, probably from either Cuzco or Puno. It was an item intended to impress and to flaunt its owner’s wealth – something of an obligation in the social hierarchy of 18th century Spanish colonial South America.

The silverwork is delirious with fecund foliage, blooms, pomegranate motifs, monkeys, squirrels and birds, and indigenous figures clad in feathered costumes with bows and arrows. The front panel incorporates a leafy, stylised crown with the letters ‘M A’ worked into the design.

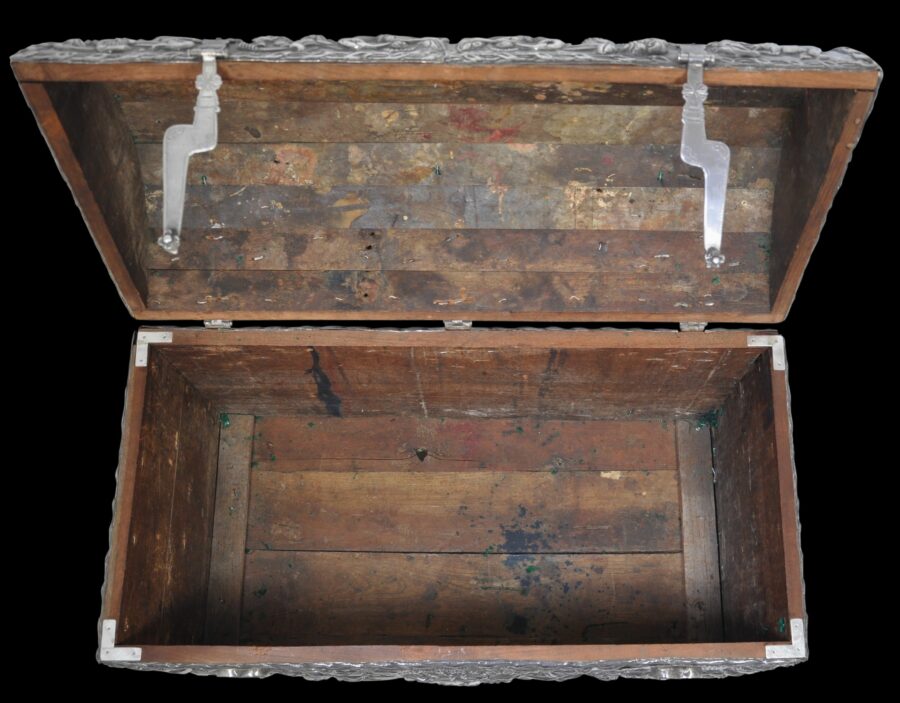

The silver sheets are pinned with silver nails to a wooden chassis or armature which has been assembled from wooden boards that have been pinned together. It stands on four silver-clad wooden ball feet. The high, hinged lid is secured on the front with two large silver lock clasps with town engraved, doubled-headed each lock escutcheons. The original solid-cast, silver keys are still present (one works the original lock readily, the other does not.) On each side are heavy solid-cast silver handles.

Repoussed silver sheets over wood was particularly popular as a technique in Cuzco. Hundreds of items (and probably more) were produced with such decoration for the many local churches, cathedrals and monasteries.

A cartouche to the top of the cover has been engraved with an ownership inscription (in Spanish) but this might be a later addition.

The pinning of decorated silver sheets over a wooden frame or chassis was a technique also used for ecclesiastic furniture such as altars and missal stands. The silver plaques sometimes came adrift and so are sometimes see in in collections as stand-alone plaques – see for example, a series of similar plaques from altar frontals attributed to the 18th and late-18th centuries published in Stratton-Pruitt (2013, p. 156-7).

The form of the chest is based on the leather bound storage trunks used in Viceroyalty of Peru known as petaca. Such chests were made for both secular and ecclesiastic use. Silver-clad, domed, wooden chests are illustrated in Argent d’Argentine (1992, p, 138), del Carmen Heredia Moreno (1992, p. 183) and Phipps (2004, p. 337).

The silver is decorated all over with writhing, scrolled leaves and fecund tropical flowers bursting with seeds and vitality – scrolling which is suggestive of Spanish-Arab influence. Various creatures and individuals in indigenous feathered costumes are worked into the vegetal profusion. There is a horror vacui that is typical of Spanish Baroque decoration – there are simply no areas left without decoration. The motifs are also arrayed within a geometric structure of borders and strapwork so that there is a tension between the scrolling profusions and the overall geometric structure that contains it.

The reverse is decorated with a central urn from which issue extravagant vegetal and floral elements. Such an urn motif is not unusual in late 18th century Spanish colonial silverwork – see Rivas Perez (2022, p. 103).

The decoration on the chest suggests that it dates to around the end of the 18th century and not earlier. The repousse work on items clad in silver panels tends to be tighter in composition, denser and more intricate, when it is earlier.

Local fauna was also incorporated into the designs of silver in South America. The designs and compositions employed followed an obvious oeuvre but within this, much variation exists – a testimony to the creativity, individualism and innovation of the silversmiths concerned. Monograms were also popular motifs employed during the colonial era.

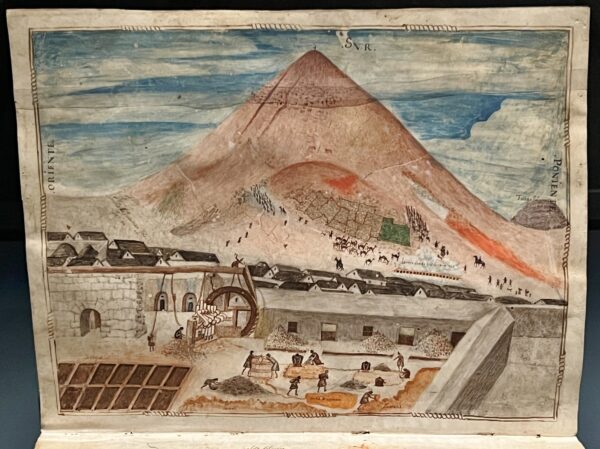

The Viceroyalty of Peru was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained what is today Peru and most of Spain’s other colonial holdings in South America. Lima was the Viceroyalty of Peru’s capital. Stately homes were built in Lima by the local Spanish aristocracy and their splendid interiors were decorated with grand items of Spanish-influenced furniture. This helped to make Lima the most Spanish city in all of South America. Buildings, both secular and ecclesiastic, were based on 17th century European classicism. Silver mined from the Potosi mines – among the most important silver mines the world has seen – funded much of this and was used locally too by local silversmiths. The shipping port of Seville connected Spain to Viceroyalty of Peru and to Manila and Mexico. The trade was known as the Galleon Trade which saw the distribution of luxury goods across the world. The flow was not one way, but complex and multi-dimensional. The Viceroyalty of Peru lasted until 1824, although over its history it went through various territorial changes.

Above: The silver mines of Potosi, illustrated in a watercolour dating to around 1585. (Photographed at the Royal Academy, London; collection of the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York.)

Baroque is a style that emerged from Rome in the early 17th century. It was a reaction to Luther’s Protestantism and the attendant austerity and so was a celebration of the supernatural with its rich, scenographic ostentation which spread from Rome to the rest of the Roman Catholic world, including the Spanish-American colonies. Included in this was the double-headed eagle with its imperial connotations, a motif which also became incorporated into the coat of arms of Lima. Baroque remained in vogue for two hundred years and for the rest of the existence of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Other motifs included cornucopias, urns and vases of flowers, rosettes and fruits and vines.

The high relief and the floral designs are reminiscent of the Dutch-influenced flower motifs seen on early Batavian silver produced in the Dutch East Indies. The link between the Dutch colonial and Spanish colonial worlds is not immediately obvious but the trade in luxury goods was such that there was a degree of cross-pollination. A silver box, clearly a Batavian betel box or perhaps a copy of one for example, is illustrated in Esteras Martin (1994, p. 307) and is attributed to Nicaragua, 1790-1800. Somehow it has made its way all the way from the Dutch East Indies.

The artistic influence between Spain and Spanish America was not one way. Much of the silver items made in Viceroyalty of Peru was exported to Spain and so it is likely that the local version of Baroque then influenced Spanish Baroque. The preference in Spain for altars, tabernacles and other items to be clad entirely in silver is something else that might have been imported from colonial South America.

The chest has no significant losses. There is the expected minor denting to the silverwork here and there consistent with age. The edges of the interior wood substrate have been re-edged probably to account for shrinkage so that the lid will fit. The interior corners have later, small silver supports to better support the box and give it greater strength. These are not visible when the lid is closed. Other steps have been taken to support the box such as wooden struts have been screwed into the interior base also to give more support, but again, this is not visible from the outside. The silver on the chest has no assay or maker’s marks. This is entirely typical of Viceroyalty of Peru silverwork. Almost no surviving silver from Viceroyalty of Peru is marked. Overall, it is a splendid, striking, large cabinet, impressive its size and extensive use of silver.

References

Argent d’Argentine, Association Francaise d’Action Artistique, 1992.

del Carmen Heredia Moreno, M., M. de Orve Sivatte, & A. de Orbe Sivatte, Arte Hispanoamericano en Navarra: Plata, Pintura y Escultura, Gobierno de Navarra, 1992.

Campos Carles de Pena, M., A Surviving Legacy in Spanish America: Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Furniture from the Viceroyalty of Peru, Ediciones el Viso, 2013.

Esteras Martin , C., La Plateria en el Reino de Guatemala, Siglos XVI-XIX, Fundacion Albergue Hermano Pedro, 1994.

de Lavalle, J.A. & W. Lang, Arte y Tesoros del Peru: Plateria Virreynal, Banco de Credito del Peru en la Cultura, 1974.

Lenaghan, P. et al, Spain and the Hispanic World: Treasures from the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, Royal Academy of Arts, 2023.

Phipps, E. et al, The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530-1830, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Rivas Perez, J.F. (ed.), Appropriation & Invention: Three Centuries of Art in Spanish America – Selections from the Denver Art Museum, Hirmer, 2022.

Rishel, J.J. & S. Stratton-Pruitt, The Arts in Latin America 1492-1820, Yale University Press, 2006.

Stratton-Pruitt, S.L., Journeys to New Worlds: Spanish and Portuguese Colonial Art in the Roberta and Richard Huber Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art/Yale University Press, 2013.

Torres della Pina, J., & V. Mujica Diez Canseco (eds.), Peruvian Silver and Silversmiths, Patronato Plata del Peru, 1997.