Enquiry about object: 9910

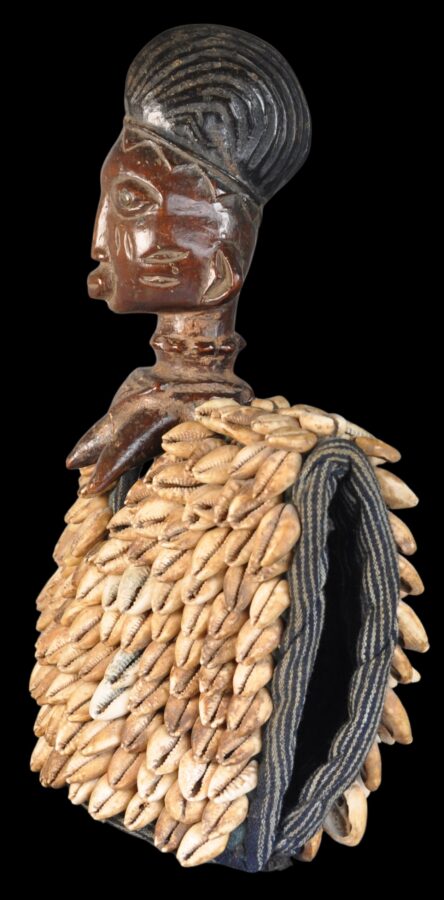

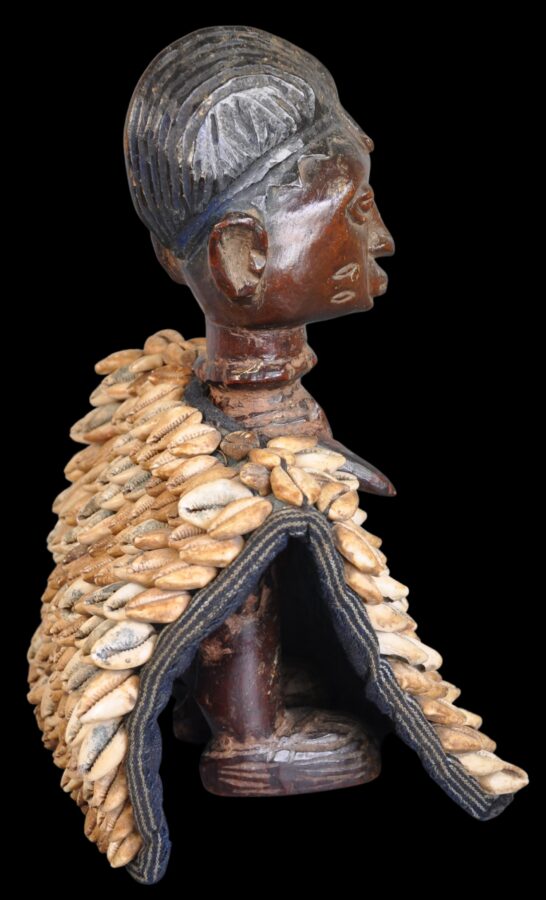

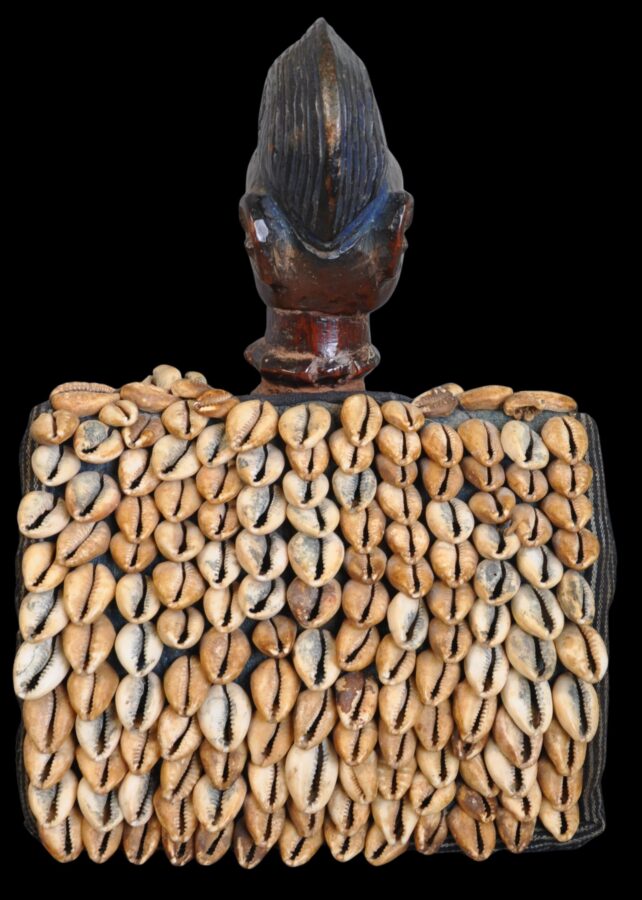

Fine, Yoruba Pair of Ibeji Female Twin Figures with Cowrie Cloaks & Tirah Talismans

Yoruba People, Northern Nigeria 19th century

height: 17 and 18.6cm, width: 19.2 and 19.7cm, combined weight: 1,987g

Provenance

Acquired from Peter Wengraf, London, 1984.

This pair of female ere ibeji twins have superb, deep, lustrous patinas, with contours softened from handling and ritual caressing. Their age is obvious. Also, they are a clear pair but they are not identical twins. Furthermore, both retain their original cloaks or costumes sewn densely on each side with cowrie shells. The cloaks and shells themselves have superb and clear age and patina. (Cowrie shells are associated with the feminine and fertility on account of their shape. Cowrie shells were also expensive and came from Africa’s east coast. The ample use of them on ibejis was to show how wealthy was their owner.)

Robbins & Ingram Nooter (1989, p. 248-9) identify ibeji twins decorated with such costumes as belonging to twins of priestly or royal lineage.

Both stand with hands on hips and with legs apart and on platform sandals. Each has particularly protruding breasts, an extended navel, and a triangular patch of pubic hair. The coiffures are high and blackened and the faces of each have ritual scarification. The hairlines of each are marked out with an unusual band of repeated triangles. Each has protruding, pursed lips, and bulging eyes.

Both have large heads: the over-sized head is deliberate – the head is where the spirit resides. Among the Yoruba, the over-sized head is associated with one’s destiny, and can be a measure of one’s likely success or failure.

Rather than being decorated with actual strings of beads and so on, each has been carved with jewellery including a neck ring, a prominent necklace with triangular pendant, and arm bands. Probably the jewellery has been carved on because it was always intended that this pair would wear their cowrie cloaks.

Claessens (2013, p. 34-35) suggests that the triangular pendants are in fact intended to represent Islamic amulets made from leather packets called tirah. These contain Koranic citations designed to protect the wearer from ill health and bad luck. Tirah were made by Huasa in the north of Nigeria and sold by itinerant Huasa merchants who made their way south in the 19th century. Claessens argues that ibeji carved with tirah are thus from the more northern parts of Nigeria. The presence of tirah did not mean that the owner of the ibeji was a Muslim; rather that the practice of wearing tirah for talismanic reasons was adopted by both Muslims and non- Muslims.

Both also show remnants of light-brown camwood powder (osun) and palm oil paste having been applied as a ritual offering. This same paste was smeared on children to protect them against illness.

Yoruba people have the highest dizygotic (non-identical) twinning rate in the world. The birth of twins amongst Yoruba women are four times more likely than anywhere else. Unfortunately, the mortality rate of the twins also was high. Ere Ibeji figures were carved as spiritual representations of the twins who died. These figures were commissioned from village carvers, who were also often highly trained priests (Babalawo). The images were carved as adults, rather than as the deceased infants. It is common in African sculpture that representations of children are made with adult-like qualities, including elaborate coiffures, scarifications on the face, fully developed breasts (on female figures), pubic hair and prominent genitalia. They were usually placed on a shrine dedicated to Elegba (a divine messenger deity) in the living area of the house and fed, bathed and dressed regularly. These figures were particularly special to the mother, who kept them close to her and caressed the figures in a loving manner, hence the wear that genuinely old examples exhibit.

The pair here has obvious age. One has old termite loss to one foot. They are excellent sculpturally and most particularly for their rich colour.

References

Bacquart, J. B., The Tribal Arts of Africa, Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Claessens, B., Ere Ibeji: Dos and Bertie Winkel Collection, Elmar Publishers, 2013.

Fagg, W. and J. Pemberton, J., Yoruba: Sculpture of West Africa, Collins, 1982.

Polo, F., Encyclopedia of the Ibeji, Ibeji Art, 2008.

Robbins, W. & N Ingram Nooter, African Art in American Collections, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Rowland, A., H.J. Drewal, and J. Pemberton, Yoruba: Art and Aesthetics,Museum Rietberg, Zurich, 1991.