Enquiry about object: 9695

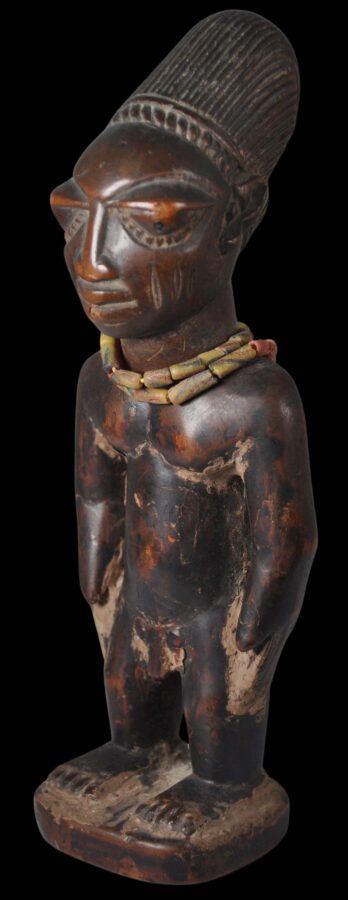

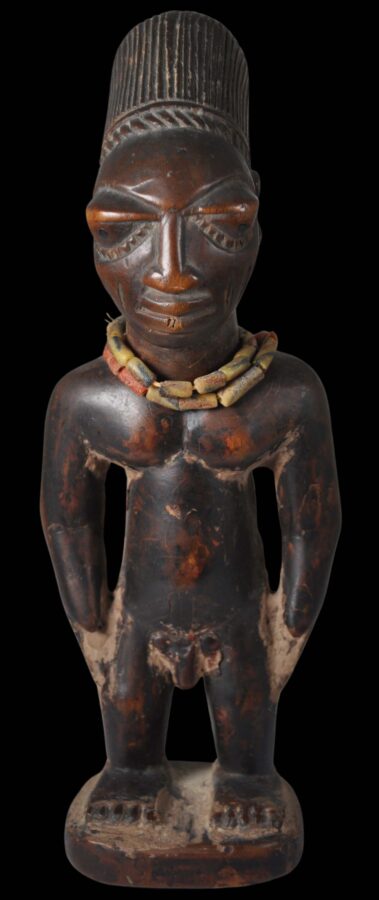

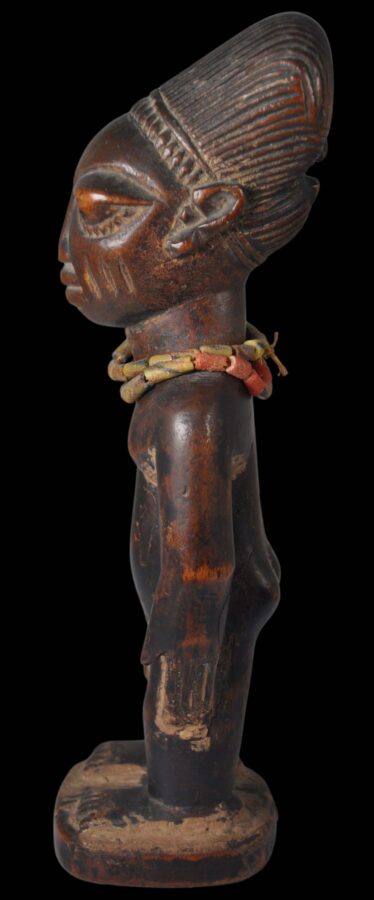

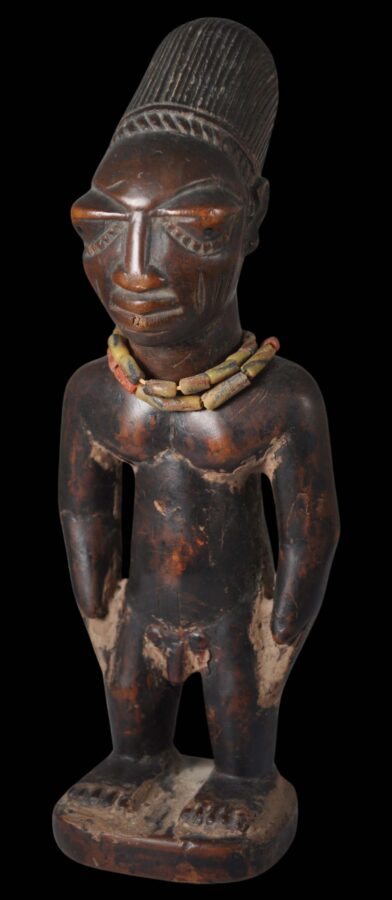

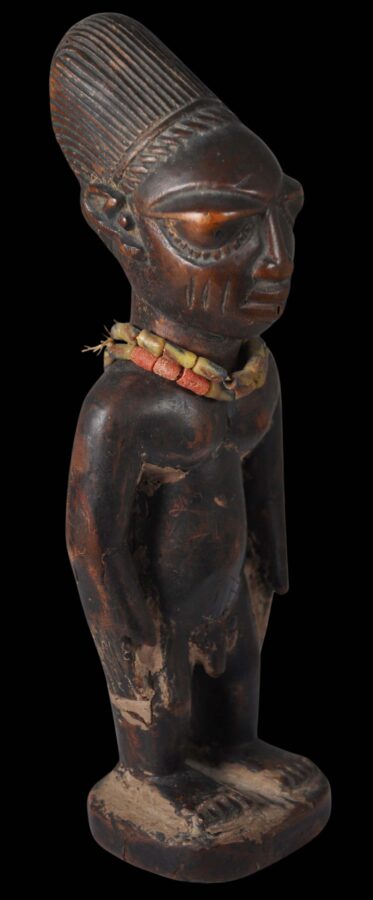

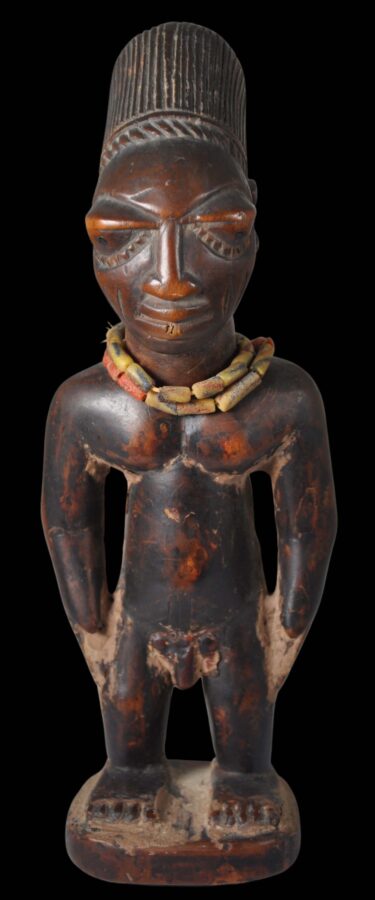

Yoruba Male Ibeji Figure

Ilogbo, Egbado Yoruba People, Nigeria early 20th century

height: 22cm, weight: 188g

Provenance

private collection, London, UK; acquired previously in the Netherlands.

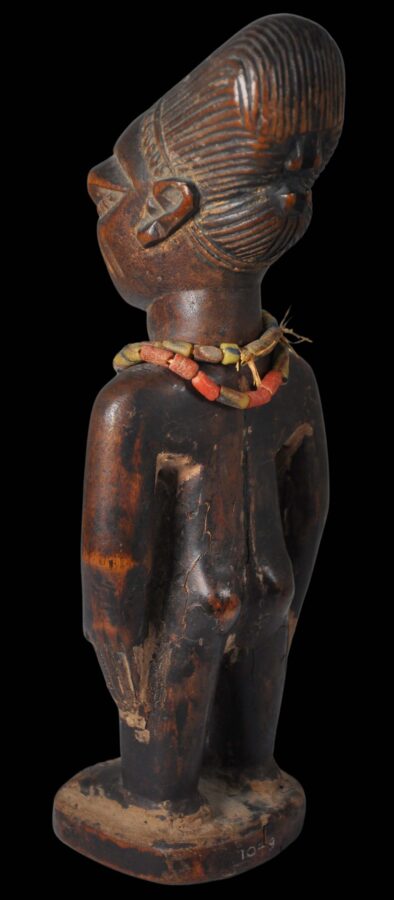

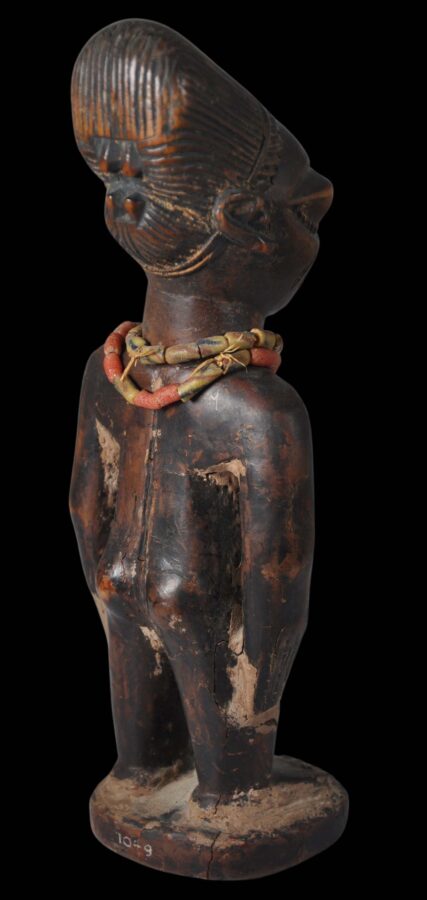

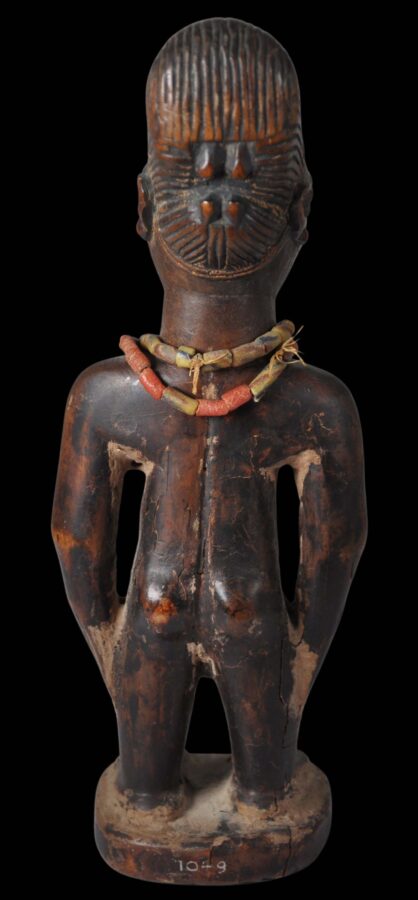

This male Ere Ibeji figure from the Egbado Yoruba, has a superb patina from age and ritual use. (Ere Ibeji is a combination of Yoruba words: ere ‘sacred image’, ibi ‘born’ and eji ‘two’.) The figure stands with his hands on his hips, has a prominent penis with incised pubic hair, elongated arms and flat, wide feet. He has a somewhat languid expression, with wide-open, bulging elliptical eyes with heavy lids. Small wooden dowels comprise the irises. His nose is flared and his lips wide and slightly parted. The ears have been carved towards the back of the head.

A set of deeply incised scarifications is on each cheek.

The hair is pulled back to the back of the head with a braid running across the hairline over the forehead, and with a complex design at the back of the head. A pair of ibeji figures with this precise hairstyle is illustrated in Polo (2008, Fig., 194).

The figure has been further decorated with two strands of glass trade beads around the neck.

Ere Ibeji figures represent a dead infant twin. However, like all such ibeji figures, this example is carved with mature or adult features, such as a strong chest, shoulders, arms, hands and feet. The arms are elongated but the legs are short. Such a contrast in the limbs’ proportions is typical of Yoruba carving.

Yoruba people have the highest dizygotic (non-identical) twinning rate in the world. The births of twins amongst Yoruba women are four times more likely than anywhere else in the world. Unfortunately, the mortality rate of the twins also is very high. Ere Ibeji figures were carved as spiritual representations of the twins who died. These figures were commissioned from village carvers, who were also often highly trained priests (Babalawo). They images were carved as adults, rather than as the deceased infants. It is common in African sculpture that child features in carving are more mature, including elaborate coiffures, scarifications on the face, fully developed breasts (on female figures), pubic hair and prominent genitalia. They were usually placed on a shrine dedicated to Elegba (a divine messenger deity) in the living area of the house and fed, bathed and dressed regularly. These figures were particularly special to the mother, who kept them close to her and caressed the figures in a loving manner, hence the wear that genuinely old examples exhibit.

The figure here stands unaided and without rocking. There is an old collection number to the reverse of the platform on which the ere ibeji stands.

References

Bacquart, J. B., The Tribal Arts of Africa, Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Fagg, W. and J. Pemberton, J., Yoruba: Sculpture of West Africa, Collins, 1982.

Polo, F., Encyclopedia of the Ibeji, Ibeji Art, 2008.

Rowland, A., H.J. Drewal, and J. Pemberton, Yoruba: Art and Aesthetics, Museum Rietberg, Zurich, 1991.