Enquiry about object: 3108

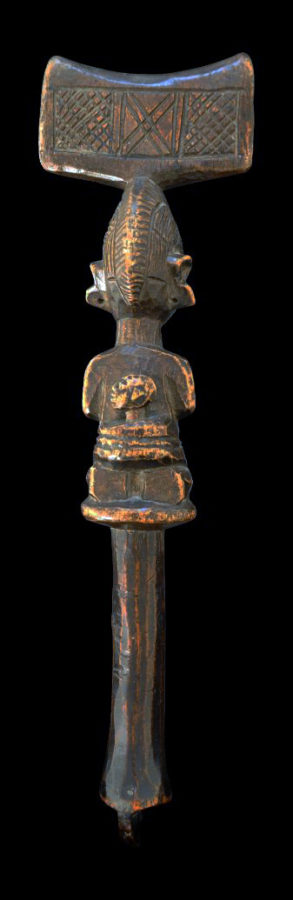

Yoruba Shango Oshe Dance Wand

Yoruba People, Egbado Tribe, Igan Okoto, Nigeria circa 1900

length: approximately 25cm, width: approximately 6cm

Provenance

acquired from the estate of Dr Peter Sharratt (d. 2014). Sharratt was a linguist and lecturer in the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh who published on Renaissance French sculpture. In his private life, he was an avid collector of tribal art, building up his collection over fifty years. During that time, he bought from UK dealers, collectors and auction houses.

This fine dance wand, or oshe, has superb patina and obvious age. Its contours have been rounded by handling, and the wood has developed a rich hue. It is carved as a supplicant female devotee of Shango, the Yoruba thunder deity. The depiction of a woman kneeling, lifting her breasts and having a baby strapped on her back is well known in Yoruba carving. It is a symbol of fertility and a gesture of greeting, offering and acceptance. Perhaps seen as naked and submissive to the Western eye, the form of the female is seen as gracious, generous and modest among the traditional Yoruba. The devotee is carved with an over-sized thunderbolt, edun ara, on her head. This aspect symbolises one’s destiny and burden. (The thunderbolt is a symbol of Shango.) Balancing the thunderbolt on one’s head is a metaphor for balancing the great power of Shango – the power that creates empires, but which also requires great care not to exceed its limits, which would bring about destruction.

The figure has bulging, semi-circular eyes; a flat nose with flared nostrils; and pursed lips, which is all suggestive of an Egbado provenance. The figure’s ears resemble angel’s wings. Her breasts are full and held forward. Three vertical scarifications (pélé) are incised on her forehead. Three horizontal scarifications (àbàjà) are incised on each cheek. The àbàjàs are more prominent than the pélés on the forehead. Overall, the female figure is almost symmetrical, except for the carving of the baby on her back.

Such a dance wands was carried by devotees at the annual festival of Shango and on other ritual occasions. During the Shango festival, devotees would dance in the streets to the thunderous rhythms of the bata drums. The dance wand would have presented a dramatic image when seen in the hand of a dancing devotee. It was waved in violent and threatening gestures to imitate the dangerous powers of Shango: unpredictable, violent, and creative and destructive – all at the same time. The Shango ritual would reach a climax when one of the devotees became possessed by Shango himself.

According to oral tradition, Shango was the fourth king of ancient Oyo Empire. He defeated the rivalrous Dahomey Kingdom. His army was famed for its skilful cavalry on the battlefield. However, Shango was also renowned for his unpredictable use of power, and his obsession with magic which often involved invoking thunder. He reigned for only seven years. His capital city Oyo-Ile and the royal family were destroyed by severe thunderstorms, apparently brought by his misuse of magical powers! He was devastated by the destruction of his family and his consequent humiliation by his chiefs. He left Oyo and committed suicide in Koso. However, thunderstorms continued to strike the Oyo Empire after his death. His chiefs built shrines and deified Shango to appease the thunderstorms.

The Yoruba is one of the largest tribes in West Africa. There are 30 million Yoruba people in West Africa, predominantly in Nigeria. The Egbado are one of the many tribes that make up the Yoruba culture. The Egbado are found mostly in the south-western areas of Yorubaland, where the ancient Oyo Empire was founded. Igan Okoto has the biggest population of the Egbado people.

Above: A Shango priestess carrying two ritual staffs, Oyo, Nigeria. Photograph: Robert Farris Thompson, 1964.

References

Abiodun, R., H. J. Drewal & J. Pemberton III, Yoruba: Art and Aesthetics, The Center for African Art and the Rietberg Museum Zurich, 1991.

Bacquart, J. B., The Tribal Arts of Africa, Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Fagg, W., J. Pemberton III & B. Holcombe, Yoruba: Sculpture of West Africa, Collins, 1982.

Polo, F., Encyclopedia of the Ibeji, Ibeji Art, 2008.

Robbins, W. M. and Nooter, N. I., African Art in American Collections, Smithsonian Institution, 1989.

Walker, R. A., Olowe of Ise: A Yoruba Sculptor to Kings, National Museum of African Art, 1998.