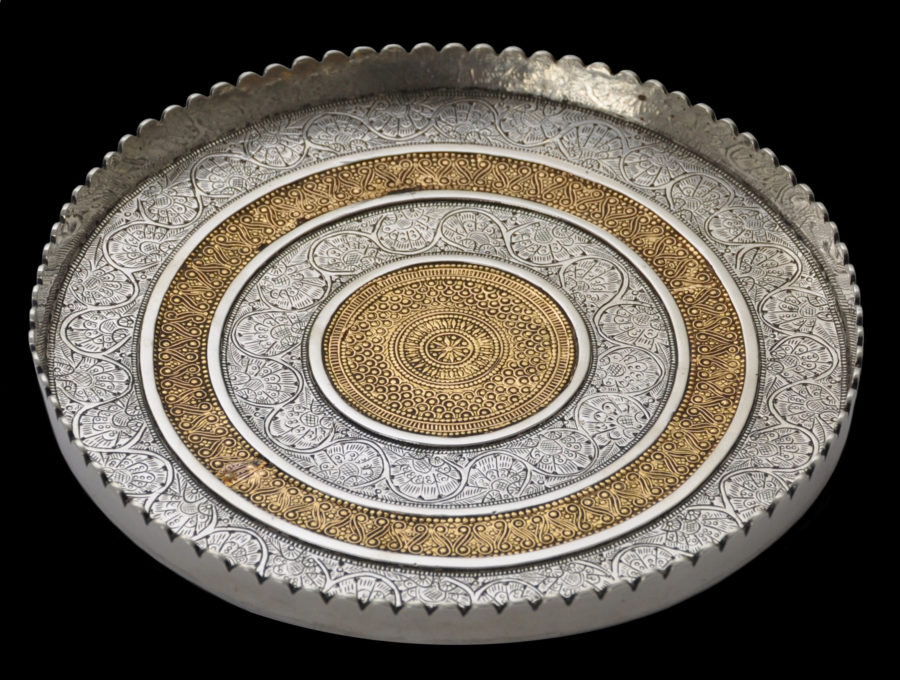

This heavy dish is of high-grade solid silver that has been inlaid with high-carat gold plaques. The silver is thick and so the dish is noticeably heavy in the hand.

The dish is from the Swahili Coast in East Africa. Most probably it is from Zanzibar. It might also be from Lamu island.

Utilitarian items of gold and silver from Zanzibar and related islands are incredibly rare. It is likely that this dish was used to serve betel nut to guests. (Betel was used as a mild social narcotic and is known in India as paan and sirih in Malaysia and Indonesia where it was also used.)

The silver of the interior of the dish is engraved with Islamic-inspired floral scrollwork. The gold panels are extensive and are within raised silver borders. The gold has been repoussed with ‘S’-shaped motifs and fish scale motifs.

The reverse is plain and unmarked. The sides rise straight up without any gradient, and the rim is scalloped, and mirrors the parapets of the high, white-washed walls that surround palace and other buildings in Zanzibar and Lamu.

The motifs used in the engraving of the silver reflect the carving seen on the elaborate doors used on the homes of the well-to-do in Stone Town, Zanzibar’s capital. (See our blog on these doors.) Also see the image below of a door lintel – the motifs on the lintel are reflected both in the engraving of the silver and the repousse work on the gold.

See another item of silver and gold that we attributed to the Swahili Coast, most probably Zanzibar.

Inset gold plaques decorated with this motifs seems to be characteristic of Zanzibar work. Such panels can be seen on the ivory hilts of Omani-influenced sword that were manufactured in Zanzibar in the eighteenth century. Examples of these swords are illustrated in Hales (2013, pp. 237-139).

Related gold panels also appear on an ivory hair comb that we had and which was attributable to Zanzibar and now in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art; on a silver and gold betel box, most probably from Zanzibar, now in a private London collection; on horn comb, now in a private New York collection; and on some knife handles, also now in a private collection.

Zanzibar items are rare – and yet Zanzibar was an important centre for trade especially in ivory, slaves, spices, grain and many other items. It linked the east coast of Africa to the Middle East and to India. As a consequence, it was an important centre for raw materials for the production of luxury goods that were subsequently traded around the world, including to Europe and the United States. It was ruled by an Islamic sultan installed in a local palace and as a consequence there was demand for local production of luxury goods as well, for the palace and related aristocrats and wealthy merchants and also to be given as diplomatic gifts. It is in this context that the gold and silver dish here can be considered.

Zanzibar comprises two larger islands and a series of smaller islands 25-50 kilometres off the coast of East Africa. Arab traders visited and traded with the islands for many centuries. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Zanzibar was under Portuguese control. And in 1698, it was sized by the Sultanate of Oman, and a ruling Arab elite with a local sultan was installed which developed the local economy further enhancing its trading links with the Middle East and with India.

Important trading communities of Muscat-descended Arabs and Indian Muslims established themselves in Zanzibar. The Indian Muslims comprised Ismailis – Khojas – and Bohoras particularly. Parsees from India also were another significant community. Another Muslim community, the Wahadimu, evolved too, by intermarriage between Africans and Arabs. Other groups included Ceylonese, Christian Goanese of Portuguese and Indian descent, and Indian Baluchis.

Zanzibar became renown as a source of ivory, spices and slaves. It also became a regional entrepot and was an important source of goods that were traded into Africa. The Sultan of Zanzibar also controlled parts of the East African coast which also facilitated this. By the mid-19th century, Zanzibar was the biggest slave centre in East Africa with around 50,000 slaves passing through its docks each year.

By the late 19th century, Zanzibar was under the control of the British. The islands gained independence from Britain in December 1963. A month later, the Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba was formed in a revolution that saw thousands of Arabs and Indians killed. The following April, the republic was subsumed into the mainland former colony of Tanganyika (later Tanzania). Zanzibar today has semi-autonomous status.

The dish here is in fine condition. It has obvious age. There is what is probably a small old repair to small section of the inlaid gold but this is not particularly noticeable in the context of the overall item. It is a rare, splendid and curious item.

References

Abungu, G. & L., Lamu: Kenya’s Enchanted Island, Rizzoli, 2009.

Dale, G., The Peoples of Zanzibar: Their Customs and Religious Beliefs, The Universities’ Mission to Central Africa, 1920.

Hales, R., Islamic and Oriental Arms and Armour: A Lifetime’s Passion, Robert Hale CI Ltd, 2013.

Meier, P. & A. Pupura (eds.), World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, Krannert Art Museum/Kinkead Pavilion, 2017.