Provenance & Possession: A Reassessment

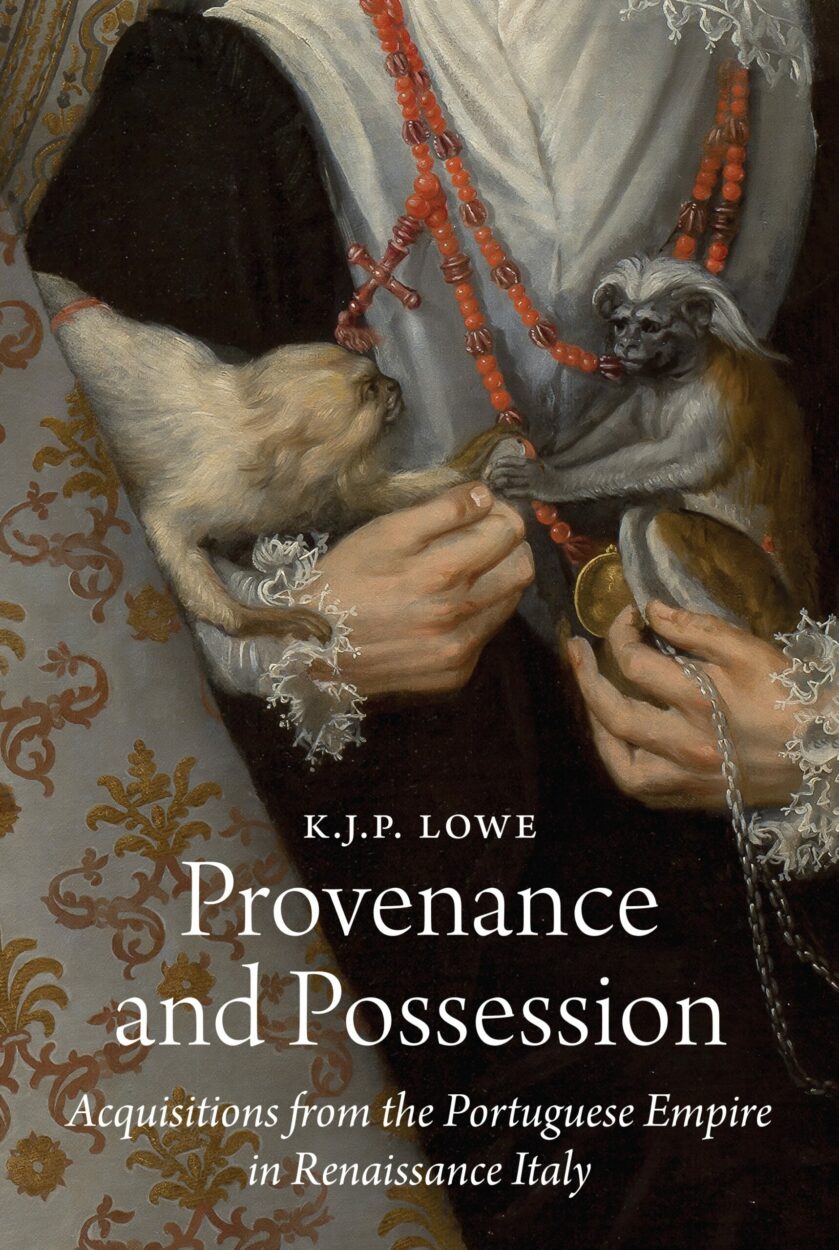

Dr Kate Lowe’s marvellous new book Provenance and Possession: Acquisitions from the Portuguese Empire in Renaissance Italy (Princeton University Press, 2024) is a revelation. By the early 16th century, the reach of Portugal’s trading empire was so great that it included the whole of Africa, India, Brazil and Asia. Consequently, luxury and exotic goods quickly spread around the world. The aristocrats of Renaissance Italy were important end-customers of Portugal’s merchants. But what did they know about where their collectables came from? Did they care?

The book’s main premise is that today provenance is regarded as critically important but provenance was unimportant in Renaissance Italy (if not more broadly). Today, curators, academics and collectors tie themselves in knots about where precisely in the world an item was made, but in the sixteenth century, when there was a thirst for the new, the luxurious and the exotic, almost no-one cared. What mattered was that an item was beautiful, exotic and that no-one else had it. Possession was everything; provenance, by comparison, largely was irrelevant. It wasn’t a conscious decision not to know. It’s more that thinking didn’t even get that far.

As Lowe says, ‘Provenance is now held to be an almost inalienable part of any object or possession of any value, a sine qua non, without which not only the authenticity but also the moral worth of the object is called into question. Provenance defines the object, and defines reactions to it.’ (p. 2). And also, ‘Provenance is a fundamental part of context, and yet in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, by itself it appears that it was often considered irrelevant,’ (p.2). By the end of the book, the author surmises that, ‘It is possible that on occasion knowledge of provenance might also have been considered disadvantageous because [it was] limiting.’ (p. 291). Indeed, knowledge of the origins of an object among Italy’s nobility might have made it seem less mysterious, more knowable, and so less exotic. Today, provenance matters and it matters a great deal. Back then, it is possible that it might have even lessened the commercial worth of an object.

One problem today in determining provenance for items that came to Italy in the Renaissance is that not only was record keeping poor with regards the true origins of luxury goods, but it was also subjective. As Lowe observes so pertinently, ‘Documents are created for a reason; without one, they do not just come into being. And the reasons for documents’ existence dictate how they are constructed and written, what is included and excluded, and what the parameters of the written material are.’ (p. 6).

To the extent that there was any knowledge of provenance, often it was given as the last port of an item’s embarkation, rather than its originating port. Among the nobility, there was a switch in the 16th century from silver tableware to porcelain. And so for example, even porcelain that was known to have been made in China but which was trans-shipped through India might be recorded as having ‘come from India’. So the place of embarkation was prioritised over the place of origin.

Additionally, there are very few surviving ships’ logs from the period and their precise routes are usually unknown. Furthermore ships’ manifests were incomplete or insufficiently detailed to reveal a great deal about the nature of what they carried. The details we so crave today were subsumed within much broader classifications of goods.

Most of the goods brought to Europe from afar in the sixteenth century came via Portuguese ships and entered Europe via Lisbon. Local trading stations operated by the Portuguese around the globe might have had knowledge as to the origins of what they were acquiring but by the time the goods reached Portugal what really mattered were questions of material, value and rarity. Says Lowe, ‘If provenance was not an issue, nor was the guarantee of authenticity that could have come with it.’ (p. 17). She makes the point that until now, the lack of provenance information has been assumed to be due to documentary loss, when in actual fact provenance wasn’t documented generally simply because it wasn’t thought important. This is an important point, and it is new. Essentially, Lowe suggests that there is little point in researchers searching today for documents that in all likelihood never existed in the first place.

Lowe further points out that documents, if they exist, undoubtedly are good to have, but the information in them is not necessarily true. Inventories are a form of documentation but usefully analysing their content does require knowledge of both the language and stylistic conventions in operation at the time. Medici collection inventories for example were compiled by Florentines and Tuscans who had probably never set foot outside Tuscany. The objects from abroad arrived already disassociated from original origins and contexts and without any oral or written explanation. The compilers might never have encountered such items before, and yet as record keepers somehow were to record them. Accordingly, descriptors such as indiano, turco, or moresco were used generically to denote foreignness.

Indiano particularly was a word used extensively to indicate foreignness. Some researchers today might take it to mean ‘from India’ but this is not correct. It was not a geographic descriptor. In Italian records, the word seems to have been used to signal generic indigenousness of the non-European. It was a word that was applied to both objects and people. When applied to the latter it was similar to the Portuguese or Spanish word ‘indio’ used to indicate ‘native’ or ‘indigenous’ but it was a label that did no more than indicate foreignness and was almost boundless in its application.

Thus, when records were constructed rarely did they allow for provenance to be recorded, but even if they did, the language of geography and provenance was poor to the point that it was either meaningless or too imprecise to be of much use to us today. Indeed, in today’s context, it can be downright misleading. Thus, it is important to distinguish between reality and representation. Lowe warns that documents must not be taken at face value, at least not initially.

The complications do not end there. Geographically-specific vocabulary was often sketchy to the point that the right words did not even exist or were not known to record provenance meaningfully even if there was intent. In the case of West Africa for example, Lowe points out that shipping charts might have recorded coastal settlements and landing places, but the Portuguese had few words for areas or regions or provinces – even the names of African kingdoms and empires often were not known, and certainly the names of ethnic or linguistic groups are unlikely to have been known or understood.

Although the author does not make this point, this was not a European problem. Africans and Asians themselves also often lacked this knowledge. At the time, the Malays for example did not necessarily appreciate that they were Malay and belonged to a wider cultural group. Instead, they identified themselves by which riverine settlement they came from. They tended not to draw broader conclusions about group identity when, whilst travelling, they met others with similar physical characteristics, customs and beliefs, and who spoke the same language but who came from other riverine settlements. Indeed it can be argued that it was European colonisation, most particularly in the nineteenth century, that saw a great uplift in the precision of defining ethnicity with its need for record keeping, a requirement for effective government administration.

Another practical problem in record keeping concerned nomenclature when it came to political entities. For the Portuguese, and undoubtedly almost everyone else, there was a lack of clarity surrounding the use of words such as ‘kingdom’, ’empire’, and ‘monarchy’ in the sixteenth century. If these concepts were troublesome, then how much more so would be the more nebulous concept of ‘region’ further complicating any possibility of noting provenance with any great precision. (p. 19). And again, to use the Malay analogy, prior to the 19th century, Malay sultans themselves had little concept of the boundaries of their sultanates. Instead, they defined their realms according to which villages submitted to their demands for taxation; geographic space was a practical irrelevance.

One exception where provenance was noted, at least at the level of names of countries for some classes of goods, was in the records kept for Catarina da Austria, Queen of Portugal between 1525 and 1578. Catarina, who married King Joao III in 1525 was to become one of the greatest female collectors in sixteenth century Europe. Provenance in this regard was felt to add to the value of the goods. But this was unusual. Generally, the value attached to provenance dissipated as items were sent beyond Portugal. By the time Portuguese trading-empire goods had made the next leg of their journey to Italy or the Hapsburg Empire, even the provenance attached to exceptional objects appears to have been shed as no longer relevant. (p. 25).

It is interesting to note that researchers today are able to posit provenance in respect of extant luxury goods to most of the well-known Portuguese entrepots of the past such as Goa and Sri Lanka but the one great such place for which no goods have ever been attributed is Malacca, which was controlled by the Portuguese from 1511 when it was captured from the local Malay sultan. Perhaps with the benefit of Lowe’s work, it seems now that the reason for this is not that nothing of note was made in Malacca, but rather that provenance was of so little interest to the Portuguese and their wider European client base that no Malacca provenance was recorded. That luxury goods were being produced locally is almost beyond doubt. The Portuguese noted such objects when they looted the Sultan of Malacca’s palace in 1511.

A good part of the book deals with ‘black’ slavery in Europe, which has long been an interest of Dr Lowe. Equating ‘blackness’ with slavery is more a modern affectation and one that serves current simplistic narratives and the need to see things quite literally in terms of black and white. And so the author makes the point that before black slaves arrived in Europe there were already many white slaves – Tartars, Russians, Mongols, Circassians and people from the Balkans. Black slaves are apparent in paintings from the period – but white slaves are not and it is possible that many Italian and other aristocrats who appear in paintings with their servants were actually painted with their white slaves. Black slaves on the other hand were only a small minority but their skin colour has made them highly visible in paintings.

‘Blackness’ though did not automatically need to infer social inferiority. Lowe cites the experience of a Kongolese ambassador who, when presented to Fabio Biondi (who was appointed by Pope Sixtus V as Patriarch of Jerusalem in 1588), was accepted without hesitation for his ambassadorial status and gained ready entry to the upper echelons of society. There is substantial evidence of the equivalence between ‘black’ and ‘white’ (p. 184). Society it seems divided on class lines, position and wealth. Division was not necessarily based on skin colour.

There is one area – not covered in the book – where the Portuguese and Italians, and many other Europeans for that matter, did care critically about provenance, and that was in the area of holy relics destined for the Catholic Church. Many of these did not come from Europe but from Egypt, Constantinople (Istanbul) and other places in the so-called Near East. Important relics commanded enormous prices and provenance was key to determining perceived authenticity. However the peak of interest in such relics was during the medieval period, so perhaps a hundred or so more years earlier than the period covered by the book.

But by and large, provenance seems to be a relatively recent concern at least in so far as exotic goods destined for the kunstkammer of Europe’s nobility are concerned. Rarely was it recorded and the lack of records is not necessarily because those records have been lost. Provenance and Possession presents a whole new way of thinking about provenance. It serves as a reminder of how unscholarly and misleading it is to extrapolate present-day obsessions and fashions back in time. Our concerns were not those of Renaissance Italy. Today, we – and especially museums – sacrifice possession because of provenance. The Renaissance Italians were not so hamstrung and were all the more splendid for it.

————–

Dr Kate Lowe is an Associate Fellow at the Warburg Institute, University of London. She has been published widely on the topic of Renaissance Europe, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, and the role of exotic luxury goods imported to Renaissance Europe.

© Michael Backman

Receive our monthly catalogues of new items by email.

See our available East-West items for sale here.

See our entire Catalogue.